“Put him to sleep!”

It’s a battle cry. One that lights a fire in football players’ hearts and psychologically prepares them to crush opponents.

For Florida starting right guard Stewart Reese, the phrase carries a double meaning. The graduate student wants to become an anesthesiologist.

“I couldn’t see myself standing and operating on people, so I decided to just sit behind the scenes and put people to sleep,” Stewart said.

Stewart always harbored a passion for the medical field, and his infatuation shone through in occasionally eyebrow-raising ways.

As a child, he woke early to watch TLC medical shows, his favorite centered around delivering babies. His wide eyes stuck to the screen until the show went off the air around midday.

He observed videos of surgeons replacing knees between bites of food at lunchtime.

In middle school, he learned about a pressure point on the head used to incapacitate attackers. Naturally, he experimented on a middle school classmate, who shrieked that she almost passed out.

Stewart’s obsession bloomed into a career aspiration. He told his mother, Patricia Reese, he wanted to be an orthopedic surgeon.

As he studied the human body, Stewart’s own grew to ridiculous proportions, which gravitated him to the game of football.

“In middle school, the kids used to try and determine how many of them it would take to take him down because he was such a big boy,” Patricia said.

Stewart initially grew too large. He couldn’t play football until ninth grade due to weight limits in younger leagues.

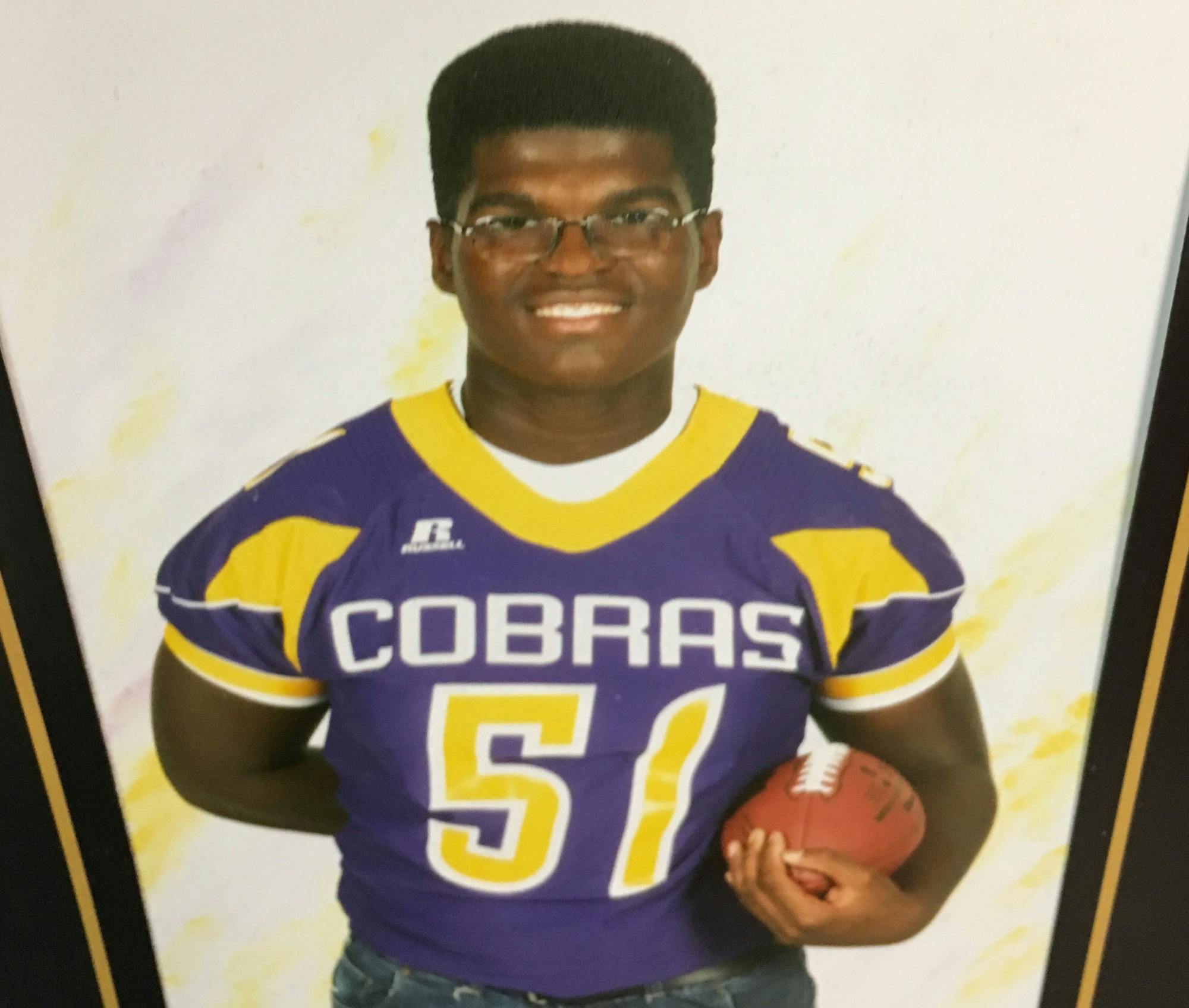

At Fort Pierce Central High School, Stewart’s size captivated scouts nationwide. Standing well above 6 feet tall and over 300 pounds, Stewart could sit crisscrossed, a show of his flexibility and movement for his stature. His father said Mississippi State recruiters were blown away by his son’s athleticism in warmup videos they watched.

No matter how much hype Stewart gathered athletically, academics came first in the Reese house.

One day during Stewart’s freshman year, Stewart Sr. checked his son’s grades and saw several classes hovering near D’s. He drove to the field, pulled his son out of the middle of practice and told him he could return to practice when his grades improved.

The turnaround took less than a week.

He moved himself to the front of the class. He began to participate, raising his hand and answering questions. Stewart read the assigned books he previously blew off that summer. The teachers were astounded by the reinvention.

It’s near impossible to place a glass ceiling on someone 6 feet, 6 inches tall, not that Stewart’s parents ever tried. In fact, the Reeses empowered their children to block out negativity. No one had the power to discourage Stewart nor his siblings from pursuing their dreams and goals.

This message was a deeply personal one for both parents, borne from positive and negative influences from their own childhoods.

Stewart Sr.’s parents always told him he could reach the greatest heights with hard work, but the world didn’t always share their confidence. Older peers told him what he wasn’t, what he couldn’t do, a damaging and debilitating reinforcement he knew too well.

“That stays with you angry,” Stewart Sr. said.

He and Patricia never wanted their children to experience that anger. Negative people, negative energy, negative environments, all weren’t allowed to hold any power over Stewart. Whatever peak he envisioned, he just needed to work for it.

Work for it, Stewart did. His dedication on the field led him to a three-star rating as 247’s 19th-ranked offensive guard in the 2016 class.

As he matured into higher levels of competition, Stewart knew careers in football and health care wouldn’t be easy to balance. The NCAA limits athletes to a maximum of four days or 20 hours of in-season practice a week, amounting to a part-time job without including travel and recovery time.

UF College of Medicine admits a 3.79 average GPA and a 514 average MCAT score. For reference, a 3.5 GPA in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences graduates with honors, and a 514 on the MCAT scores in the 92nd percentile.

But like his parents taught him, difficult doesn’t mean impossible, and Stewart’s confidence never wavered.

He drew inspiration from Laurent Duvernay-Tardif, who started at right guard for the Kansas City Chiefs. The Canadian earned his Ph.D. in medicine from McGill University in 2018, all while playing professional football. He helped the Chiefs to a Super Bowl victory early in 2020 but later shelved his pads for PPE to serve on the front lines against COVID-19 in his home country.

So Stewart didn’t compromise. He committed to Mississippi State in February 2016, a program then run by current Florida head coach Dan Mullen and offensive line coach John Hevesy.

After a redshirt year, he played 26 straight games at right tackle across the 2017 and 2018 seasons, anchoring the second-best rushing offense in the SEC before moving to right guard in 2019.

Even in Starkville, he didn’t forget the lesson his father taught him when he pulled Stewart from the field. He earned his way onto the 2016 SEC First-Year Academic Honor Roll and collected SEC Academic Honor Roll honors in 2017 and 2018.

Dreams of orthopedic surgery gradually gave way into anesthesiology as he juggled blocking sleds and biology tests, but his doctoral dreams never died.

After four years as a Bulldog, Reese returned to his home state when he transferred to Florida in May 2020. He not only reunited with his Mississippi State coaches, Mullen and Hevesy, but also his younger brother, outside linebacker David Reese.

He started 11 games at right guard for the Gators last season, an experienced and reliable presence situated between Kyle Trask and opposing defenses.

College athletes typically don’t suit up longer than five years before they lose eligibility. With the COVID-19 pandemic hanging like a cloud over the 2020 seasons, the NCAA allowed all fall student-athletes a free year of eligibility, which gifted Stewart a sixth year to bolster his draft stock and continue his march toward medical school.

“We just prayed about it,” Stewart said, “and when they made the statement that they were going to be allowing us to come back, we were happy. I can't be happier to be back.”

Stewart isn’t the only Reese sibling with aspirations in the medical field.

Brandon, his older brother, worked as a paramedic in Jacksonville, and Stewart saw his brother’s work up close and personal, like when he walked through an ambulance after a critical care transport.

“Seeing what I'm doing, he's probably more comfortable doing it because he sees me in that role and he's hung out with me and he sees what my life is like,” Brandon said.

While at Mississippi State, Stewart flew out to visit his brother, who now works as a nurse in Las Vegas, and witnessed the field again when he met doctors and walked through the hospital Brandon calls an office.

As he ambled through the halls of his brother’s workplace, the veil of mystique and professionalism gave way to familiarity.

“A lot of people have this fear of healthcare and doctors and stuff like that, but they're just normal people, and he saw that,” Brandon said.

Stewart hopes to be one of those normal people one day, though medical school may wait if the NFL comes calling. A professional career wouldn’t slow Stewart down at all, it would be another layer of the plan.

He wants to inspire kids everywhere, especially young athletes who feel scared to pursue lives off the field and away from the gym.

“A lot of times people always push, especially kids that are big, athletic, they'll always tell them 'Play sports, play sports,’” Stewart said. “I think, a lot of times, they have other dreams and aspirations outside of sports. Because sports is so popular, they usually get caught up and just play sports and never really pursue anything outside of it.”

Stewart hopes his success, both wearing a Gator helmet and a white coat, shows children there’s more to an athlete than highlight tapes and letterman jackets.

In the meantime, however, people still need to be put to sleep and Stewart Reese will be the man for the job.

Contact Ryan Haley at rhaley@alligator.org and follow him on Twitter @ryan_dhaley

Ryan Haley, a UF journalism senior with a sports & media specialization from Jacksonville, Florida, is Summer 2022's Engagement Managing Editor. He grew up playing a bunch of different sports before settling on golf, following Rory McIlroy and all Philadelphia sports teams. He also loves all things fiction, reading, watching shows and movies and talking about whatever current story or character is in his head.