A new set of legislation signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis Monday will affect community gatherings and protests deemed violent by law enforcement.

House Bill 1, also known as the “anti-riot” or “Combatting public disorder” bill, passed the Florida Senate on Thursday to a 23-17 vote. DeSantis’ staff wrote in a statement the day of the vote that he was “looking forward” to signing the bill into law, and he signed it Monday morning.

“We wanted to make sure that we were able to protect the people of our great state, people’s businesses and property against any type of mob activity or violent assemblies,” DeSantis said before signing.

The bill will increase penalties for illegal actions during riots and make it a felony to destroy any monument in the state.

In Gainesville, a college town where the median age is about 26, organized demonstrations occur frequently. Students and longtime residents often plan protests following major national events like January’s Capitol insurrection, the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg and the Atlanta spa shootings. Although Gainesville protests almost never descend into violence, some students and local activists are worried about the precedent the legislation will set.

The Gainesville Police Records Department could not provide information regarding protester arrests in the city before publication.

The law has garnered attention from Florida lawmakers and activists like Oluwabusayo Oni, a 20-year-old UF biomedical engineering sophomore.

One of her biggest concerns, Oni said, is being denied bail until her first court appearance if she were arrested at a protest.

“I shouldn’t have to hesitate to speak out on human rights,” Oni said. “If an officer can arrest me and charge me with a felony, it could ruin my life.”

DeSantis first introduced the bill in September following Black Lives Matter protests that escalated in the summer. After George Floyd, an unarmed Black man was murdered in police custody, protests erupted throughout the city, state, country and world. In some parts of Florida, law enforcement intervened. Police officers used tear gas to control crowds in Orlando, Miami, Tampa and Jacksonville, and nighttime curfews were issued in several counties and cities.

DeSantis later cited the insurrection at the U.S. capitol in January as a reason to file the bill.

House Bill 1 supporter Rep. John Synder, R-Stuart, wrote in a TCPalm opinion column that he supported the bill because it provides protection for police and keeps roads and highways from being blocked. As someone from a family of law enforcement officers, the most important provision, he wrote, was the six-month minimum mandatory jail sentence for battery of an officer in a riot.

“It is my view that HB 1 balances the rights enshrined in our Constitution with the rule of law that keeps our society from descending into chaos,” he wrote in the column.

The bill defines a riot as a “violent public disturbance involving an assembly of three or more persons acting with common intent,” which would be punishable by a third degree felony. Depending on the offense, the punishment could range from a $5,000 fine to a 10-year prison sentence.

Aggravated rioting, which is also mentioned in the bill, is defined as nine or more people causing “great bodily harm,” as well as the use of a deadly weapon, threatening vehicles on the road or property damage of more than $5,000. These acts are punishable by a second degree felony.

Bob Dekle, a retired UF law professor and prosecutor, said HB 1 won’t impact peaceful protests at all. The major change the bill makes is that it toughens penalties for people engaging in unlawful activities in protests.

“As long as you're standing there waving a sign saying ‘the mayor must go’ or something like that, nothing is going to happen,” Dekle said. “You have a right to do that.”

Dekle said the terms in the bill do not seem loosely defined, such as aggravated rioting, which is constituted by multiple terms.

“You don't need a Webster dictionary to figure out what the language of any one of those provisions is,” Dekle said.

However, Florida Democrats and activists still worry that some of the terminology in the bill could have unintended consequences and be used against peaceful protestors.

Irfan Kovankaya, a 23-year-old recent UF graduate, was living at home in Tallahassee when he was arrested at the Florida Capitol in September for attending a protest prompted by the shooting of Tony McDade, a Black transgender man. At the protest, Kovankaya was charged with unlawful assembly, a misdemeanor that’s still pending trial.

The day of, Kovankaya had his hands zip-tied and was thrown into the back of a police van. But he can’t imagine the long-term impact it would have had on his future if his charge had been a felony.

“It would have ruined everything for me,” he said. “I've done everything right in terms of respectability politics. I graduated from the University of Florida. I got a double major. I had a good GPA. But, ultimately, none of that's going to matter.”

Gainesville City Commissioner David Arreola said House Bill 1 is reminiscent of the type of law that failing regimes pass when they are losing control.

“This is beyond ridiculous,” Arreola said. “This law can not stand.”

The bill has very ill-defined parameters, Arreola said. One could technically argue that an unruly UF tailgate is a mob.

Arreola said he was proud of how Gainesville reacted this summer organizing Black Lives Matter protests. He said the demonstrations never were violent and strictly followed mask compliance.

He’s worried about cities across Florida after the bill passes. It’s important that he be clear with Gainesville law enforcement agencies that he does not tolerate abuse of force, and police leadership has agreed.

“It is a dark day for Florida,” he said.

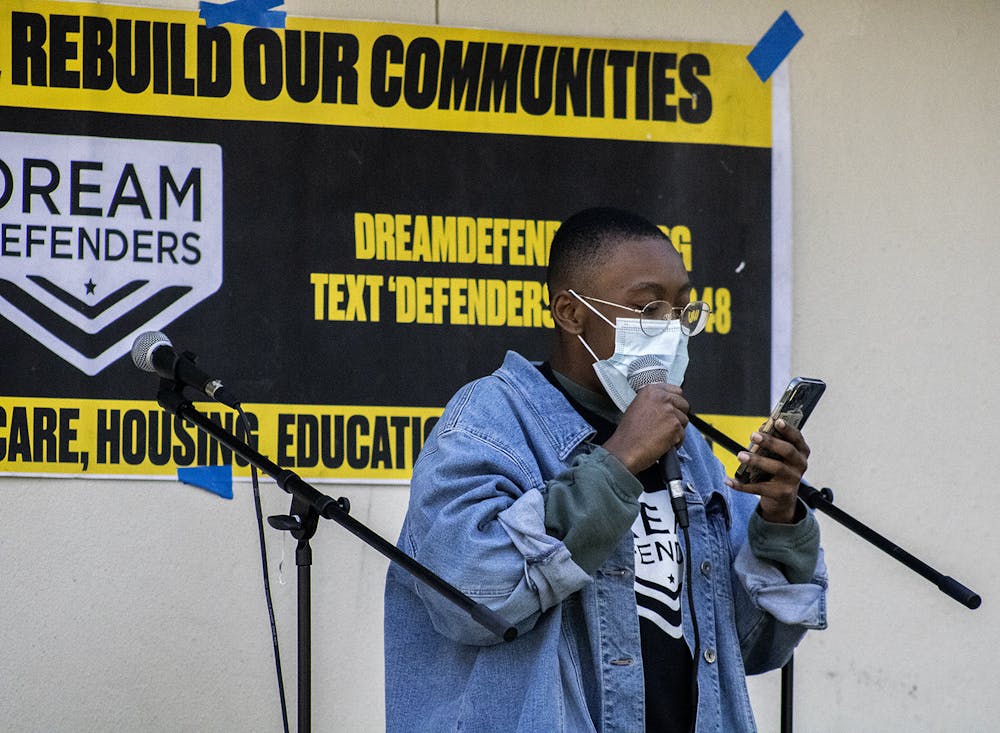

On April 2, about 60 people gathered outside T.B. McPherson Recreation Center in East Gainesville to protest HB 1. GoDDsville Dream Defenders, a local chapter of a national organization founded after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin died, hosted the afternoon event.

Kiara Laurent, a 22-year-old Gainesville community organizer, said the event was supposed to be a “community gathering,” rather than a traditional protest. Attendees sat on a field, cheered for performances and clapped in support of speakers. Among them were spoken word poets, local musicians and community organizers.

“This is more like a party,” she said. “The sole purpose was to come together and bring awareness to how the bill can threaten and risk our lives, and to engage with people who want to demand change in our communities.”

Laurent said the local chapter of Dream Defenders has helped coordinate statewide efforts to call legislators and take trips to Tallahassee when the bill was on the floor of the legislature. Her goal in lobbying against the bill was to protect those who might be dissuaded from protesting because of it, although she said it wouldn’t prevent her from continuing to do so.

“We still have a community here,” she said. “We will do anything we can to protect that community.”

Candace Ochsenbein, a 49-year-old Gainesville resident, attended the protest with her daughter Hailey, a 19-year-old Santa Fe education freshman. As a new resident of Gainesville, she wants to support Hailey’s desire to participate in the city’s thriving activism scene.

However, with the looming threat of possible felony charges for protestors, she began to consider the possible consequences.

“I don't want to see her go to a protest and for some silly reason she winds up in jail as a result,” she said. “A lot of the time, violence occurs for other reasons, not because of the actual protest that's taking place.”

Contact Alan Halaly and Anna Wilder at ahalaly@alligator.org and awilder@alligator.org. Follow them on Twitter @AlanHalaly and @anna_wilderr.

Anna Wilder is a second-year journalism major and the criminal justice reporter. She's from Melbourne, Florida, and she enjoys being outdoors or playing the viola when she's not writing.

Alan Halaly is a third-year journalism major and the Spring 2023 Editor-in-Chief of The Alligator. He's previously served as Engagement Managing Editor, Metro Editor and Photo Editor. Alan has also held internships with the Miami New Times and The Daily Beast, and spent his first two semesters in college on The Alligator’s Metro desk covering city and county affairs.