It was 1954, and about 30 Florida A&M University freshmen sat in a classroom during orientation. A student in the back row, W. George Allen, was the first to stand up and introduce himself.

Allen said he was the first in his family to attend college. Working in medicine or law would give him satisfaction –– but the way he pronounced “satisfaction” enticed a student in the front row to interject.

The student turned and said, “‘Satis-fi-cation?’ Do you mean ‘satis-fact-ion?’”

The class broke out into laughter. Allen squinted.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Hayward J. Benson Jr.”

“I hate you.”

Sixty-five years later, Benson still laughs about the squabble that brought them together. They stayed friends until Allen died at 83 on Nov. 7.

“[That] was the kind of fighting spirit that he used throughout his life,” Benson, also 83, said. “He is one of the ones who came out of that segregated system and plotted strategies to get others out.”

Allen graduated from UF’s Levin College of Law in 1962, making him the university’s first black graduate. He led the legal fight for Broward County and Hendry County integration and later established his own practice specializing in personal injury, insurance defense and wrongful death law, according to Levin Law archives.

Allen was born on March 3, 1936, in Sanford, Florida. He was raised in a house without electricity by his mother and stepfather and worked in crop fields as a child, he said in an interview with The History Makers, the nation's largest African American oral history collection.

Growing up, Allen was told over and over again that he wouldn’t succeed.

When he went to Fort Holabird in Baltimore, Maryland, to become a special agent after graduating from Florida A&M, the instructor said nobody in the class would make it.

“[Allen] felt the eyes of everybody in the class looking at him, and he said, ‘I don’t know why the hell you’re looking at me. I’m gonna graduate.’ And he did,” Benson said.

When Allen went to law school, the professors told the class nobody would graduate –– but Allen did. He spent 50 years in the industry, he said in a speech at UF in 2015.

Allen turned down admissions offers from the University of California in Berkeley and Harvard to go to UF because he wanted to be in the south during the civil rights movement, according to Levin Law archives.

Going to school in the south wasn’t easy. As the only black student in UF’s law school, persevering against racism was a constant struggle. He and his wife couldn’t live in married student housing because they were black, and he received constant death threats via telephone, he told Florida Trend in 2013. He told the callers to go to hell.

After graduation, Allen tackled cases for equal housing, first-degree murder and desegregation in education, among others. But to those who knew him, he was more than a tenacious lawyer –– he was a respected leader and friend.

Patricia West, now 67, first met Allen when she was 8 years old. Her father was a member of the Elks Club with Allen, a group of black professional men that worked with social service agencies to help the community.

She remembers him as a snazzy dresser, always in a suit with wire-rimmed glasses and a hat. He looked after West’s family after her father died and always made West laugh, she said.

“He was a determined kind of guy,” West said. “Whatever he set his mind to, he was gonna get it finished.”

Benson however, saw Allen as a close friend who made amazing hot sauce. The two loved fishing and cast their lines out in Florida, South America, Central America and Alaska, he said.

Allen would always eat a Snickers bar when they fished. Benson bought him one when Allen was in the hospital, but he never got the chance to eat it.

Benson still has some of Allen’s hot sauce in his kitchen.

“He’s probably mixing some [hot sauce] up now,” Benson said. “I'm going to miss my fishing buddy.”

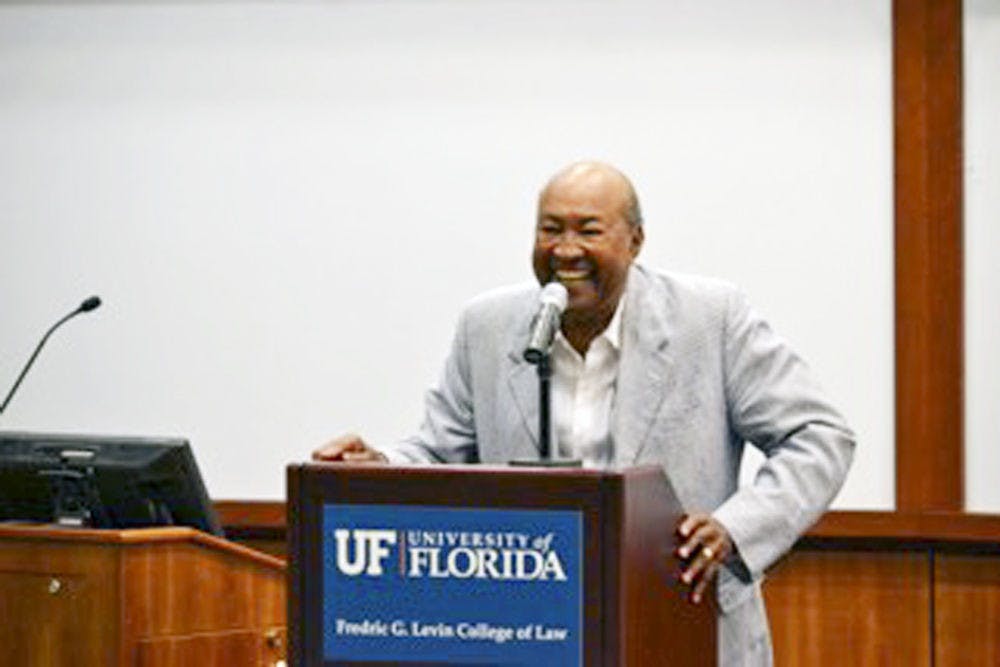

W. George Allen, the first African-American graduate of the UF College of Law, speaks to the Black Law Students Association and the Josiah T. Walls Bar Association on Friday.