When Jade Floyd moved into her Alachua home five years ago, she expected a peaceful neighborhood in a quaint, quiet town.

Her backyard, edged with trees, hinted at lazy afternoons on the porch with her pit bull-German shepherd mix and three domestic shorthair cats. Within weeks of moving in, she discovered the Copeland Industrial Park lurking behind the greenery. Her picture-perfect paradise was soon replaced with the clamor of machinery, late-night traffic and a barrage of generator noise during hurricane season.

“It was extremely loud,” Floyd, a 44-year-old patient care coordinator, said. “It sort of took me off guard that it was so loud.”

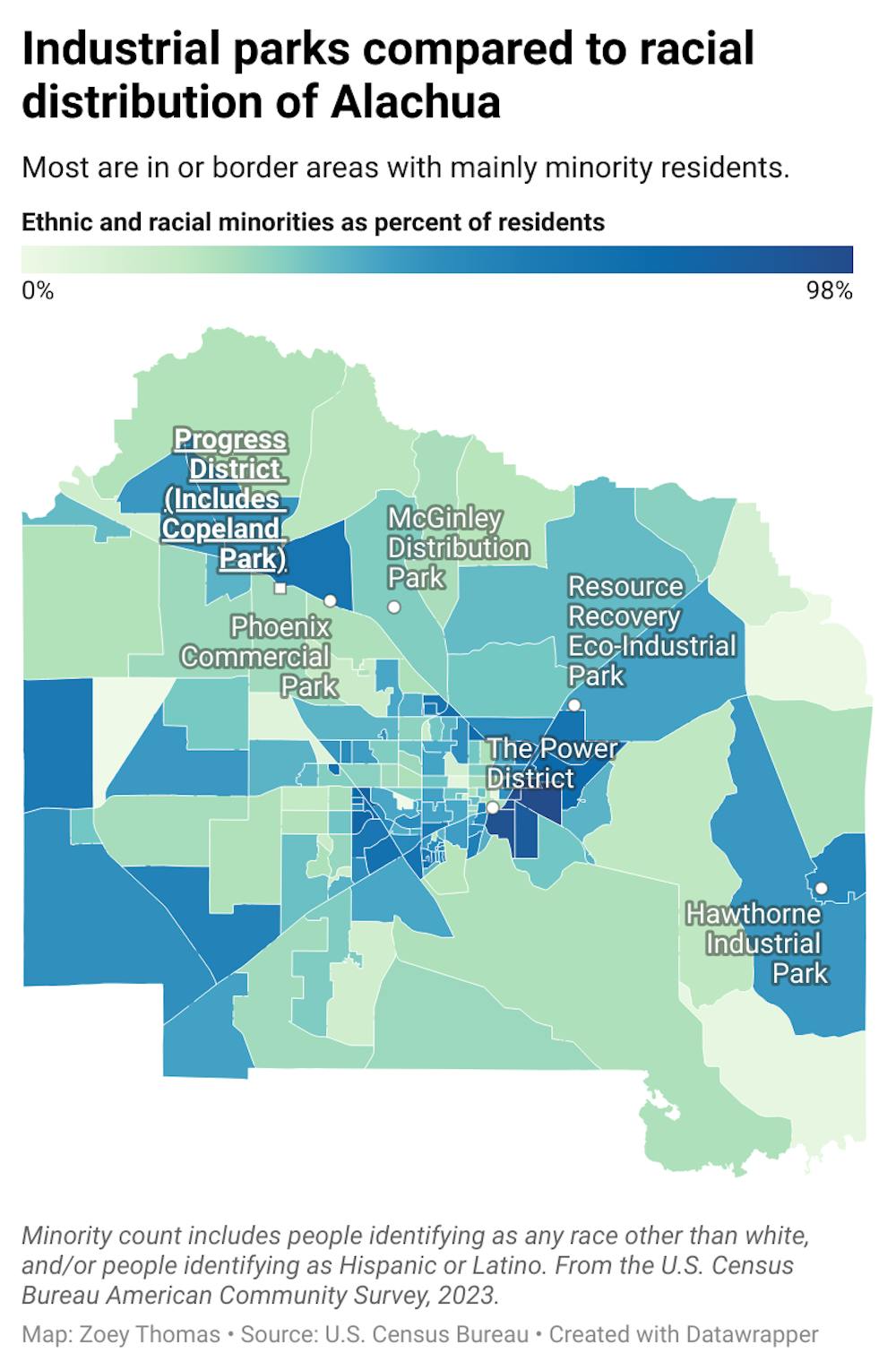

Industrial parks are areas specifically zoned for manufacturing, logistics and business operations, designed to foster economic growth and provide jobs by clustering industries in a centralized location. However, they can present challenges, particularly when placed near residential areas.

Issues like increased noise, air pollution and traffic often arise, raising concerns about the impact on nearby communities. Establishing an industrial park typically involves zoning approvals, infrastructure development and attracting businesses, which can bring significant economic benefits but also requires careful planning to balance industrial expansion with community well-being.

Copeland’s past

The Copeland Sausage Company was Alachua’s main employer for nearly 50 years, until its closure in 1978. The plant accounted for half of Alachua’s tax revenue, Mayor Gib Coerper told The Gainesville Sun in 2013. Nearly 500 people, most of whom were Alachua residents, had worked at the plant. When the Copeland property was revitalized in the late 1990s as an industrial park, it marked a new chapter for the local economy.

It’s now home to multiple businesses, research laboratories and manufacturers, which create jobs and diversify Alachua's economic landscape.

Floyd’s encounter with generator noise is just one example of everyday realities for those living near Copeland. The challenges exceed disrupted sleep from constant noise — residents worry about increased pollution, road wear and changes to the neighborhood’s character.

These concerns have only amplified as the park grows. In 2021, the CDMO Resilience acquired the largest part of the park, which it shares with Alchem Laboratories, SynQuest Laboratories, one empty development site and Lacerta Therapeutics, a gene therapy start-up that shut down last year.

Floyd said neither the seller nor her realtor mentioned the park during her home purchase.

“It would be nice to [have known],” she said. “It does sort of make me wonder, what is going on back there?”

Under state law, real estate disclosures generally cover known defects or hazards, but an adjacent industrial zone doesn’t necessarily qualify. As a result, homeowners like Floyd may discover the Copeland Industrial Park’s proximity only after unpacking their lives.

Noise and no answers

During hurricanes, backup generators from the park’s facilities reverberate day and night. Floyd said she noticed sporadic manufacturing or lab-related clamor at late hours of the evening, an intrusion she never expected in a suburban-style neighborhood.

“I just want to enjoy peace and quiet,” Floyd said. “But it was definitely not peaceful.”

Without a homeowners association to advocate for their concerns, residents find themselves without a formal mechanism to address environmental and quality-of-life issues, Floyd said.

Gladys Walker, an 80-year-old retiree who has shared a backyard with the industrial park since 2007, said her neighbors facing these challenges are primarily older adults.

"There's nothing [that] has been done,” Walker said. “They told us over and over that there is no ordinance for noise."

Walker, like Floyd, was never made aware of the existence of the industrial park or of the ongoing developments, like new plants or laboratories, in her years living next door. Many of these residents have deep roots in Alachua, having lived in the area for decades, she added, making leaving undesirable.

A park without a manager

One persistent question among residents is: Who’s in charge of maintaining the area?

Under typical circumstances, a large industrial park might have a professional management firm or property owner who sets rules, enforces hours and mediates problems. But that’s not the case with Copeland.

Sandy Burgess, the Copeland Industrial Park Owners Association manager, said the group was founded in 2000 to uphold basic covenants, collect fees and maintain stormwater basins. But the association doesn’t operate like a property manager or landlord; its only responsibility is to the property owners.

“[The association] doesn’t have any obligations to surrounding property… If there is a request at the city level, or a building permit or land use change, then there’s a mechanism for communication,” Burgess said. “But that’s not a responsibility.”

If a facility runs late-night shifts with idling trucks or if a generator rattles the neighborhood in the wake of a storm, local homeowners are on their own, she added.

This gap between industrial operations and residential living highlights a key tension in Alachua’s zoning approach. While some Florida cities, like Gainesville or parts of Marion County, enforce stringent buffer zones or require extensive public notice when an industrial use abuts a residential area, Alachua’s rules are less robust. Oftentimes, as long as land already carries an industrial designation, new construction proceeds with minimal discussion or mandated notice to neighbors.

Alachua follows a comprehensive plan designating land parcels as residential or industrial.

Gainesville’s land development code includes conditional use approvals and public hearings if the development of industrial land could disrupt surrounding areas. A prospective occupant might face noise abatement measures or certain time-of-day limits. Some other Florida counties also require enhanced buffering, rows of trees or walls to reduce sound. None of these measures appear to have been fully deployed when Copeland was developed.

“As long as the land use is in line with the covenants and with the city zoning, then it’s approved,” Burgess said.

Copeland and beyond

Aaron Turner, a 71-year-old Alachua resident, has lived down the street from the Copeland property for nearly 50 years. He said he remembers when the land was transformed into an industrial park 26 years ago.

“I don’t remember [the city or developers] informing me I wasn’t involved in it,” he said.

If an existing business within Copeland wants to operate overnight or expand, the city can easily approve those hours as “industrial use.” This straightforward process means those who live next door might never hear about it until the noise or fumes hit.

Copeland sits surprisingly close to residences, sharing a fence with residents like Walker — a fact many buyers discover too late. In contrast, other industrial parks in Gainesville, like the Airport Industrial Park and the SiVance Chemical Plant, are far enough from major neighborhoods to spare most homeowners.

Thomas Quarles, a 67-year-old minister, noted that despite a few occasional annoyances, the industrial complexes near Gainesville generally haven’t intruded on quiet neighborhoods. Quarles is a minister at Lighthouse Worship and Deliverance Ministries, which is nearly a mile away from the Airport Industrial Park and SiVance Chemical Plant.

Quarles characterized his own retired community as “really quiet.” While occasional nuisances exist, he said, the industrial facilities around Gainesville haven’t significantly impacted the tranquility of surrounding neighborhoods. Instead, he added, the sporadic smells and boisterous noises stem from a nearby landfill and gun range.

“This is a retired neighborhood,” Quarles said. “I just hear the bird chirping and the crickets.”

Gainesville’s industrial development typically keeps significant buffers, like green belts or sound walls or has been historically located away from large residential clusters. The City of Alachua, however, has industrial and residential zones sitting shoulder-to-shoulder.

While Gainesville’s industrial sites seem like a distant issue to Quarles, nearly 15 miles away, Floyd, Walker and Turner struggle to get a good night’s sleep.

Contact Vera Lucia Pappaterra at vpappaterra@alligator.org. Follow her on X @veralupap.

Vera Lucia Pappaterra is the enterprise race and equity reporter and a second-year journalism major. She has previously worked on the university desk as the university general assignment reporter. In her free time, she enjoys deadlifting 155 lbs. and telling everyone about it.