Michelle Castronover wasn’t keen on owning chickens. But when her husband and daughter asked to build a coop as a “COVID project,” the 49-year-old Shell Elementary teacher agreed.

Three years later, the Castronovers own 10 chickens — the maximum allowed to residents by Gainesville’s Fowl, Chickens or Livestock Code — and share their eggs with the neighborhood through the “fresh eggs” box standing on the edge of their front lawn, which they restock regularly with six- and nine-egg-sized boxes. The coop is just one of the family’s backyard sustainability projects, along with a greenhouse and butterfly garden.

The fresh eggs box went up in February when Michelle, her husband and their two children couldn’t eat eggs as quickly as they collected them.

“We were getting so many eggs we couldn’t give them all away,” said Michelle’s husband, 53-year-old UF police sergeant Gregory Castronover. “I figured, ‘Well, let me go ahead and put this up and anybody that wants chicken eggs can come.’”

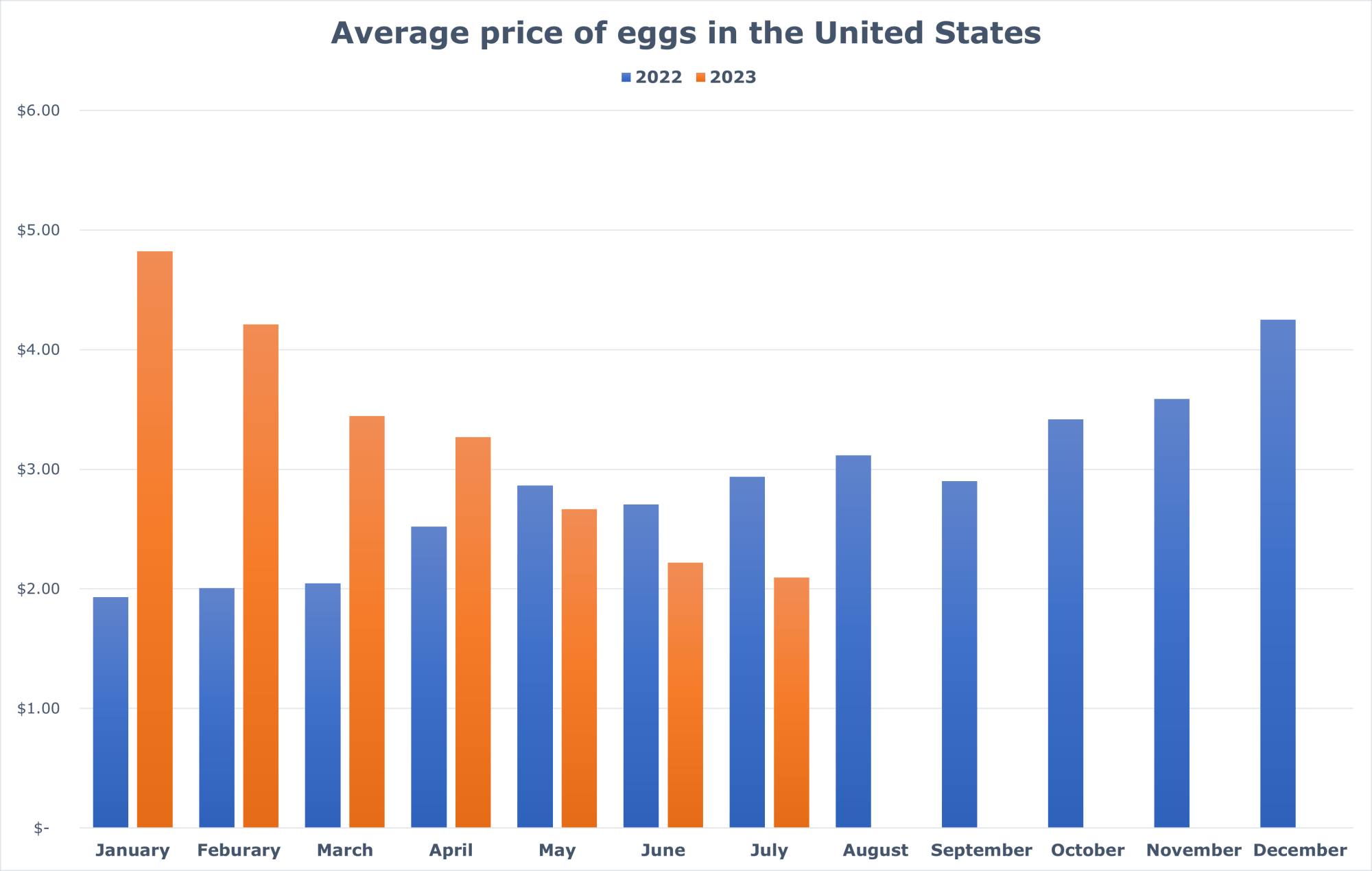

In February, U.S. egg prices saw a 70.1% inflation rate at $4.21 per dozen, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Michelle and Gregory were grateful their backyard coop protected them from rising prices, and they wanted to share their high-quality goods with neighbors who couldn’t afford free-range eggs from the grocery store.

“The prices were stupidly high. I mean, they were crazy,” Gregory said. “So if somebody needed a six-pack of eggs or a nine-pack and they didn’t have any money they’d just come get them.”

The box was a “huge hit,” and the Castronovers have yet to see any eggs spoil in the box before getting picked up by a hungry neighbor, Michelle said.

“Some of the neighbors said their kids prefer to come get our eggs — they call it the ‘egg box’ — instead of going to the grocery store,” Michelle said. “And we have one lady we actually put eggs to the side for, and she comes twice a month to collect all her eggs.”

Michelle beelines to the coop after waking up every morning, where she usually finds about seven eggs waiting for her. What doesn’t go into the box gets used to make her favorite breakfast: an over-easy with toast. Fresh eggs were an acquired taste, she said.

“I always thought fresh farm eggs look disgusting to me because I'm just so used to the store-bought ones,” Michelle said. “But now that I'm eating these, I don't ever want to have to buy eggs from the store again.”

Backyard chicken-raising is on the rise due to people like the Castronovers who picked up the hobby during COVID. As of September 2022, 12 million Americans own chickens, according to the American Pet Association.

In Gainesville, the code allowing residents up to 10 chickens but prohibiting other livestock, like roosters, was updated last year to specify the type of hen allowed to Gallus domestic hens, said Rossana Passaniti, Gainesville public communications officer. The code has proved unproblematic for the city, other than the occasional noise complaint, Passaniti said.

“That’s when oftentimes roosters are discovered on the property,” Passaniti said. “Code enforcement manages these requests and they will issue a warning … to educate individuals about what’s permitted.”

Passaniti does not own or live near backyard chickens herself but applauds those who take on the responsibility, she said.

“It’s a big responsibility, but they’re beautiful creatures,” she said. “And certainly if you have the property, being able to have fresh eggs sounds absolutely delightful.”

The hobby is environmentally friendly as well as boredom-busting. Many backyard flocks act as bio recyclers by eating leftover fruit and vegetable scraps. One chicken that eats a diet of 25% food scraps can eat more than 25 pounds per year in waste, according to Chicago Botanical Garden. The Castronovers incorporate compost into their own coops’ diet.

“I love to save leftover raw veggies for them,” Michelle said. “They love it.”

The roost sits adjacent in the Castronover’s backyard to another one of Michelle’s COVID-originating passion projects: her “Monarch Motel,” a milkweed greenhouse, butterfly garden and screened hutch, all built by her husband and registered with the nonprofit conservation program Monarch Watch as an official Monarch Waystation.

Monarch Waystations help protect the species from habitat loss due to urban development and the widespread use of herbicides. Monarchs were recently declared endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Butterflies, like chickens, didn’t interest Michelle originally — until she witnessed an upsetting scene in her garden.

“I had all these big beautiful caterpillars, and the next day I noticed they were just all gone, and I’m like, ‘Where are my caterpillars?’” Michelle said. “Then right in front of me, a wasp goes down into the milkweed and comes back up and is carrying a big caterpillar and flew away with it.”

Michelle researched monarch butterfly life cycles and was “heartbroken” to discover only one out of 100 caterpillars survives to become a butterfly, she said.

“I understand it’s part of the ecosystem, but I was just like ‘No, there’s just too many getting eaten by predators,’” she said. “I want to save some of them.”

Michelle grows milkweed in her greenhouse, bleaches the plants to eliminate disease and allows butterflies to lay eggs on the leaves before carefully moving plants into the screened-in butterfly hutch, where the insects are safe from predators until they metamorphosize.

“It’s a lot of work, but I don’t mind it,” Michelle said. “It’s something to look forward to when I get home. Of course, other than my family.”

Michelle receives stickers from Monarch Watch by mail that she uses to tag and track the butterflies that pass through her home to contribute to research on migration patterns. Last monarch season, she tagged over 30 butterflies, and although none were discovered again, she plans to repeat the process this year.

“I’m in a lot of butterfly groups on Facebook, and sadly, a lot of the people up North who do what I do will never see one monarch all summer long,” said Michelle. “There used to be a lot more that would fly all the way up to Canada, and it just seems like the number of migrators seems to be less.”

Michelle spreads her love for conservation to her second-graders at Shell Elementary, where she regularly brings in caterpillars to educate her students about the Monarch life cycle.

“[Michelle] is the butterfly queen,” said fellow second-grade Shell teacher Leila Powell, 37. “She makes science come alive for the kids … they are 100%, totally, completely enamored and cannot get enough of it.”

When the butterflies are ready to fly, the entire second grade holds a party to celebrate the release of the creatures they watched grow from egg to insect. Michelle’s passion for butterflies is infectious and reflects her devotion to her students, Powell said.

“She always, always, always puts the kids first,” Powell said. “She shares that she was a quiet kid who she felt fell through the cracks, and she made it her mission to make sure that she is meeting the needs of all of her students.”

Michelle plans to continue tagging butterflies for the remainder of “butterfly season,” which lasts from March to October, and she’ll be keeping the fresh eggs box stocked and ready for egg-loving passersby.

Contact Zoey at zthomas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @zoeythomas39

Zoey Thomas is a media production junior and The Alligator's Spring 2025 data editor. She previously reported for the metro, university and enterprise desks. In her free time, you can find her reading, crocheting or arguing for the superiority of sweet potatoes over regular potatoes.