As she kneeled in front of a freshly plowed patch of dark brown dirt encircled by a wooden fence in Reserve Park, Kimberly Brown smiled at her daughter Bella.

“Remember what I told you? How the roots are?” Brown said, raising an herb to show the 7-year-old. “It's the plant’s blood vessel, you see, because that's how ours is on the inside. It's a system — that’s how they get their water.”

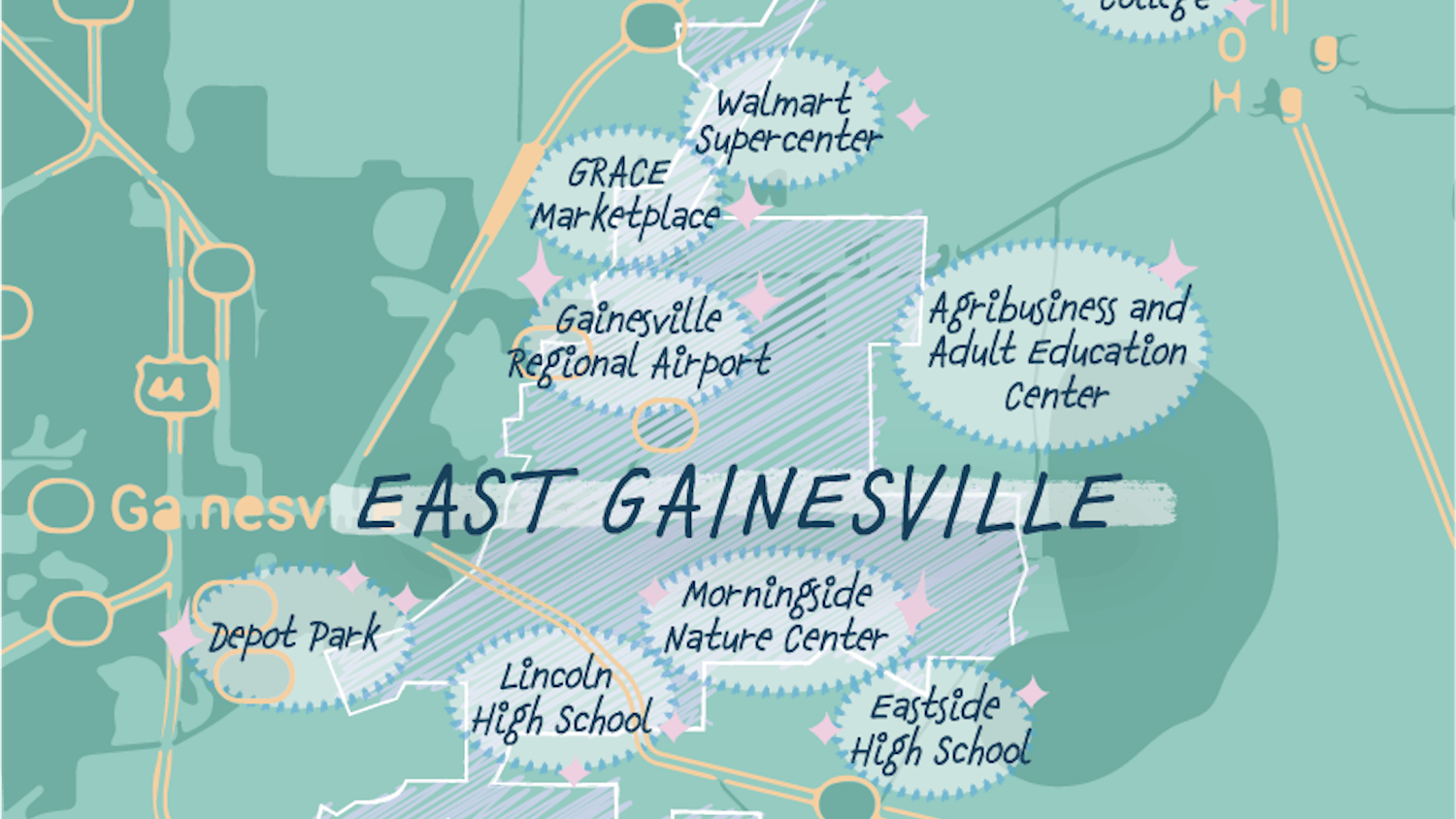

The 30-year-old Gainesville resident is one of more than 60 members of the Gainesville Black Garden Network, a Facebook group where Black residents share their gardening experiences. The group is working on a plot located in one of several community gardens throughout the city. These efforts are important to East Gainesville, where several neighborhoods qualify as food deserts. Walmart is the only one USDA-approved grocery store east of Main Street within city limits.

Community gardens like the one at Reserve Park are part of a citywide effort to increase food security since the first one was built in 1998. Each garden is equipped with a hose and a handful of plots that belong to other residents who applied to get one from the city. Plot owners water others’ plants when they drop by the gardens, an unofficial rule to keep the plants growing.

Denisha Williamson-Walker, a 36-year-old Gainesville resident and founder of the Facebook group, said she never thought she’d find a community of Black people who enjoy gardening until she posted a question in the “Gainesville Word of Mouth” Facebook group, asking if there were other Black gardeners in the city.

She received an overwhelming response and decided to create the city garden group as a way for Black residents to share photos and videos of the home gardens they worked on during the COVID-19 pandemic. The group has more than 60 members as of April 2, and the community grows each month.

To Williamson-Walker, gardening has been a way to cultivate happiness while in quarantine with her wife and son.

Her intention to farm on this plot, Williamson-Walker said, was to give Black residents in the neighborhood access to fresh food.

“I like being in the dirt,” she said. “It's soothing and therapeutic. It keeps you grounded.”

The plot in Reserve Park was donated to the group by Kelley Tomlin, a 33-year-old East Gainesville resident. Tomlin applied for the plot when the park opened last year. However, when she became pregnant with her daughter, she looked to pass the land along to a worthy cause.

After meeting Williamson-Walker online, Tomlin was thrilled to donate the plot to support Williamson-Walker’s goal of creating a space that could become a community food source for Black residents in the surrounding neighborhood.

“She’s very inclusive and even invited me to be a part of all their activities,” Tomlin said. “It’s a really, really positive group.”

Williamson-Walker came to the plot Monday afternoon with Brown and her daughter to not only grow a variety of fruits, herbs and vegetables, but a community as well. The pair hosts events for Black residents to share their love of horticulture together. Prior to Monday’s session, the group had a seed swap where members exchanged plant seeds for their home gardens.

Brown started to garden with her daughter at the start of the pandemic, mostly growing collards, a member of the cabbage family. A little over a year ago, she helped Bella tend to a strawberry plant, which now is bearing unripened strawberries.

As a licensed clinical social worker at Kimberly Kares Counseling, Brown’s private counseling practice, she often recommends gardening to her patients. She believes they can learn to love themselves by loving a plant.

“I always tell my clients that have issues with self esteem and depression to go get a plant and name it after themselves,” she said. “Then you're watering yourself and you grow with it.”

The group hopes to continue growing their online space.

Nate Porter, a 32-year-old East Gainesville resident who is new to the Facebook group, said while he grew up caring for his grandfather’s garden, life got in the way of cultivating his own as an adult.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Porter found time and started using his backyard and other greenspaces around his house to plant crops such as peppers and peanuts.

It’s an activity he brings his two children and wife into for family bonding. Each family member plants the crop they love the most. He said he puts in as many hours as he can to maintain it.

“It’s my diffuser. It’s my therapy,” he said. “When I'm frustrated after a long night at work, the next morning I go and sit out there and drink my coffee. I go through the crops, play with them and plant some stuff. It’s just a relief.”

Ultimately, the food service worker has found a sense of peace in the midst of COVID-19 chaos through his home garden — and he’s not alone.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@alligator.org. Follow him on Twitter @AlanHalaly.

Alan Halaly is a third-year journalism major and the Spring 2023 Editor-in-Chief of The Alligator. He's previously served as Engagement Managing Editor, Metro Editor and Photo Editor. Alan has also held internships with the Miami New Times and The Daily Beast, and spent his first two semesters in college on The Alligator’s Metro desk covering city and county affairs.

![Joseph Scott, 60, stands next to his personal garden at GRACE Marketplace. [Photo courtesy to the Alligator]](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/ufa/39196edc-14c8-4652-9479-b2297238c68b.sized-1000x1000.jpeg?w=1500&ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=faces&facepad=3&auto=format)