Any humanities student will tell you that they have been repeatedly asked something along these lines: “What do you plan on doing with your major?” Most of us have our rehearsed responses: “I’m not sure yet!” or “Maybe law school.” But after a while, you wear down and begin to secretly wonder, along with everyone else, what exactly you will do with a classics or philosophy degree. At least, this has been my experience.

Humanities students must constantly defend themselves and their choice of major to the outside world. Consequently, they must, at some point, make a choice: Either English is worthwhile, or I’m wasting my time. Either reading Sartre or Melville or about the French Revolution is valuable to study academically, or these are only good for private enjoyment. I know people who have regretted choosing to study the humanities and people who felt compelled to major in what they loved. It is not, by any means, a simple choice.

I am of the latter camp, and I want to defend my choice and the choice of my humanities brethren — but not in the way most professors or College of Liberal Arts and Sciences advisors would. Defenses for studying the humanities tend to focus on the meal rather than the recipe: The humanities make you a great future employee, some say, or the humanities stretch your sense of self, thus strengthening your empathy.

These arguments assume there is tremendous ethical power in writing papers on Homer or reading Nabokov, and doing either, or both, inevitably makes you a better person. But this is unclear to me. If this were the case, as the literary critic Stanley Fish has pointed out, humanities professors would be the kindest, most virtuous people on earth. It doesn’t take long, though, to discover that they are as virtuous as anyone else in the world.

The humanities may make you a better employee too, but that is not why I would recommend them to an incoming freshman. Frankly, college is unnecessary, and sometimes can even set people back, for a person to become a potentially productive citizen and worker. Being an English major among swarms of business majors is an intriguing way to distinguish yourself in the job market, but what you get out of reading Shakespeare or Dante is much more valuable than job skills to put on a resume.

I feel tugged in these two directions, always reminding people there is something special about the humanities but that it is not the only legitimate path to virtue or employment. The question must be asked, then, why did I remain an English major? Better still, why should someone pick up Nietzsche in their spare time? What do the humanities actually do?

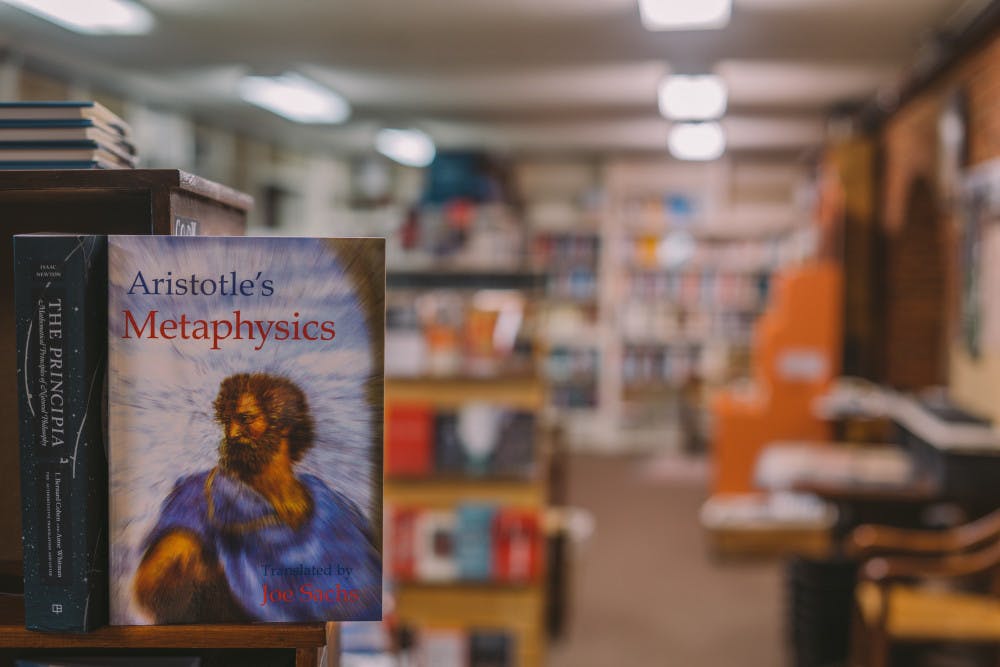

I remained an English major because I love to read authors who wrestle with life. The humanities are a culmination of how people see the world; it is learning about the various self-portraits of our past and present. There is power in learning what deep thinkers have said about deeply human questions. It changes you.

And yet, I think what I have been trying to communicate is that there is only so much power in the humanities. Too many philosophers and poets and theorists have become intoxicated with their own work and thought it superior to the sciences or business.

Indeed, how you view life will certainly change, at least in some degree, if you learn the complexities of poetry. But is it reasonable to think that Homer will stop you from disliking yourself or holding a grudge? Homer was a person, too, struggling through life like the rest of us. So were Milton and Plato and Austen. Perhaps we should learn to ask less of them and use what we have learned from the humanities to look at ourselves and our lives and see where improvement is needed.

Scott Stinson is a UF English senior. His column appears on Wednesdays.

Photo by Tbel Abuseridze on Unsplash