Lawton M. Chiles Elementary was an A-graded school — until it wasn’t.

In 2011, parents received a letter from then-principal Judy Black explaining that Chiles failed to meet its progress goals for the year. Its state-assigned grade, based on student performance on standardized tests, dropped to a B.

The final lines of the letter point an accusatory finger.

“Black, economically disadvantaged students need to make improvements in reading and math,” according to the letter.

A parent who received the letter said she was appalled. She still keeps a copy of it today.

“My black child didn’t make your grade go down,” she said. “When you say stuff like that, it just reinforces what a lot of wealthier parents already think.”

She pulled her son from Chiles soon after receiving the letter. She is currently a public school teacher in Alachua County and spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution from school authorities.

The problem expressed in the Chiles letter isn’t exclusive to Alachua County. All over Florida, school grades indicate that the success gap is growing between white and black students — the Florida public school grading system isn’t working to close that gap, experts say.

The Alligator reached out to the Florida Senate for comment, but they did not respond before publication.

Money matters

In 1999, the Florida legislature passed the A+ Plan for Education, which gave way to the A through F grading system for schools. Test-based accountability was meant to track and improve public education by offering incentives to higher-scoring schools, said Jackie Johnson, the spokeswoman for Alachua County Public Schools.

The consequences of this plan are becoming more evident 21 years later. School grades are used to determine how much and what kind of funding a school receives, but Johnson said this doesn’t take challenges disadvantaged students face into account.

“There have been many concerned that it’s an overly simplistic way of reflecting what’s going on in a school,” she said. “A lot of things affect a child’s behavior on a standardized test.”

Schools that earn an A grade also earn an “A+ bonus,” a supplemental pot of money that may go to the salary of a school’s teachers and other school staff. It can additionally be used to purchase new resources like textbooks and computers, Johnson said.

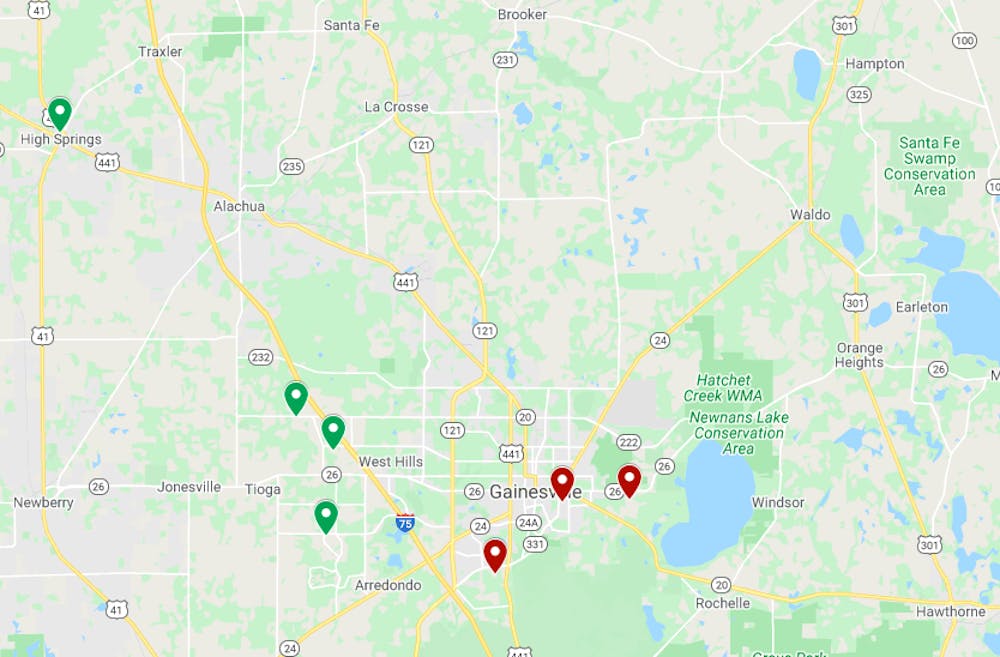

Of Alachua County’s 20 public elementary schools, four earned A’s and three earned D’s in 2019. Three of the A schools, located exclusively in West Gainesville, were given bonuses. The D schools, located exclusively in East Gainesville, weren’t.

Low-performing schools do receive money elsewhere. Title I is an initiative that provides economically disadvantaged schools with more funding to support supplemental staff and longer instruction time.

But these resources aren’t enough to close the gap, said Carmen Ward, the president of the Alachua County Education Association. Many of the schools earning the A+ bonus are already afforded more resources than lower-graded schools by virtue of their location, she said.

“Everything comes back to funding,” she said.

Schools in West Gainesville benefit from active parent-teacher associations and newer facilities than schools in East Gainesville due to the socioeconomic makeup of families zoned for those schools, Ward said.

The PTA at Kimball Wiles Elementary School raises enough money to supply teachers with $200-$500 grants each year, she said. The Westwood Middle School PTA is currently fundraising to purchase a 3D printer worth $723, according to a fundraising website.

“It’s disgusting,” Ward said. “Every student in the state should have the same experience and resources, no matter their ZIP code.”

Racial barriers

Most of Alachua County’s low-grade schools are located in East Gainesville. Data from the Florida Department of Education shows these schools have students with more economic disadvantages and disabilities, as well as more non-native English speakers, compared to schools in West Gainesville.

These factors are barriers to student success, Johnson said.

“It’s like asking us to start a race,” said Valerie Freeman, the county’s equity director. “Except one of us is missing a leg.”

The percentage of economically disadvantaged students at Idylwild and Lake Forest Elementary Schools in East Gainesville was 100 percent in the 2018-19 school year, according to state data. That same percentage at Hidden Oak and Meadowbrook in West Gainesville was around 33 percent.

Idylwild and Lake Forest are currently D graded schools. Hidden Oak and Meadowbrook are both graded A.

A majority of the students who attend Alachua’s disproportionately disadvantaged schools such as Idylwild, Lake Forest and Joseph Williams Elementary Schools are black, according to data from the Florida Department of Education.

Grades aren’t good indicators of a school’s value, said the teacher who withdrew her son from Lawton M. Chiles Elementary, a high-performing school. The success gap is exacerbated by racial discrimination at schools of all grades.

Within the first week of school, her son was recommended for lower-level reading classes, she said. These would take place while other students attend extracurricular classes like art and recess.

“I said, ‘No, we’re not doing that,’” she said. “‘The boy can read. Give him more time.’”

Later in the year, her son was tested again. This test revealed he was gifted and in need of a more advanced curriculum. She said that his teacher didn’t want to give him a chance to excel, which is common for black boys in school.

“White boy Tommy walks in the classroom jumping up and down, and it’s OK. The teacher doesn’t say anything,” she said. “But James, on the other hand, comes in, and he’s jumping up and down and suddenly there’s a problem.”

County solutions

Alachua County launched an equity initiative in 2018 to bridge the success gap between East and West Gainesville schools by improving grades. The initiative encourages equity-based teacher training and looks to hire more literacy and math coaches for low-income schools.

Freeman said the standardized tests used to calculate school grades don’t take into account each student’s unique circumstances.

“Our job is to level the playing field as much as possible for all students,” she said.

This means connecting parents who never completed high school with College Board recruiters. It means providing students with laptops, so they can do their homework and training staff on how to engage low-attending students, she said.

Changing teachers’ mindsets and mode of operation is an important part of this process, Freeman said. There is now a greater emphasis on cultural sensitivity and delivering curriculum in a way that is understood by all students, regardless of their background.

“Just because we thought it was the right way before doesn’t mean it’s the right way for every student,” she said.

The teacher who pulled her son out of Lawton M. Chiles Elementary said having teachers understand the cultural differences of their students goes a long way. But the hardest part is getting teachers to have those conversations.

“Immediately, a teacher feels attacked,” she said. “Or they’ll say, ‘I didn’t come into education to hurt anyone.’ Right. No one did. But some of the things you do unknowingly are hurting children.”

Freeman said equity will take time, but it’s necessary for student success. She said she won’t be complacent, even when the quantitative data shows they’ve reached their goals.

“Equity work can be a fad,” Freeman said. “My job is to make sure that we don’t back off. This is the right thing to do.”

Contact Hannah Phillips at hphillips@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @haphillips96.

This map shows the Alachua County public elementary schools graded A (green) and D (red) in 2019. Westside schools earn a bonus from the state for earning two consecutive A’s. Eastside schools, which face unique academic challenges that contribute to their low scores, do not.