Scherwin Henry couldn't have chosen a better place to raise his family.

The former District 1 Gainesville City Commissioner swells with pride reminiscing about his childhood in East Gainesville. Henry, 67, remembers how he played the drums in Lincoln High School’s marching band and attended Springhill Missionary Baptist Church service with his family on the weekends.

Henry’s home brimmed with social activity as neighbors and friends visited to enjoy his father’s barbeque cookouts. Though he doesn’t live in his childhood home anymore, Henry enjoys maintaining a relationship with his neighbors. He chats with them from across the fence between their homes.

“East Gainesville is a community that has a lot of beauty and character,” Henry said. “It is the original Gainesville.”

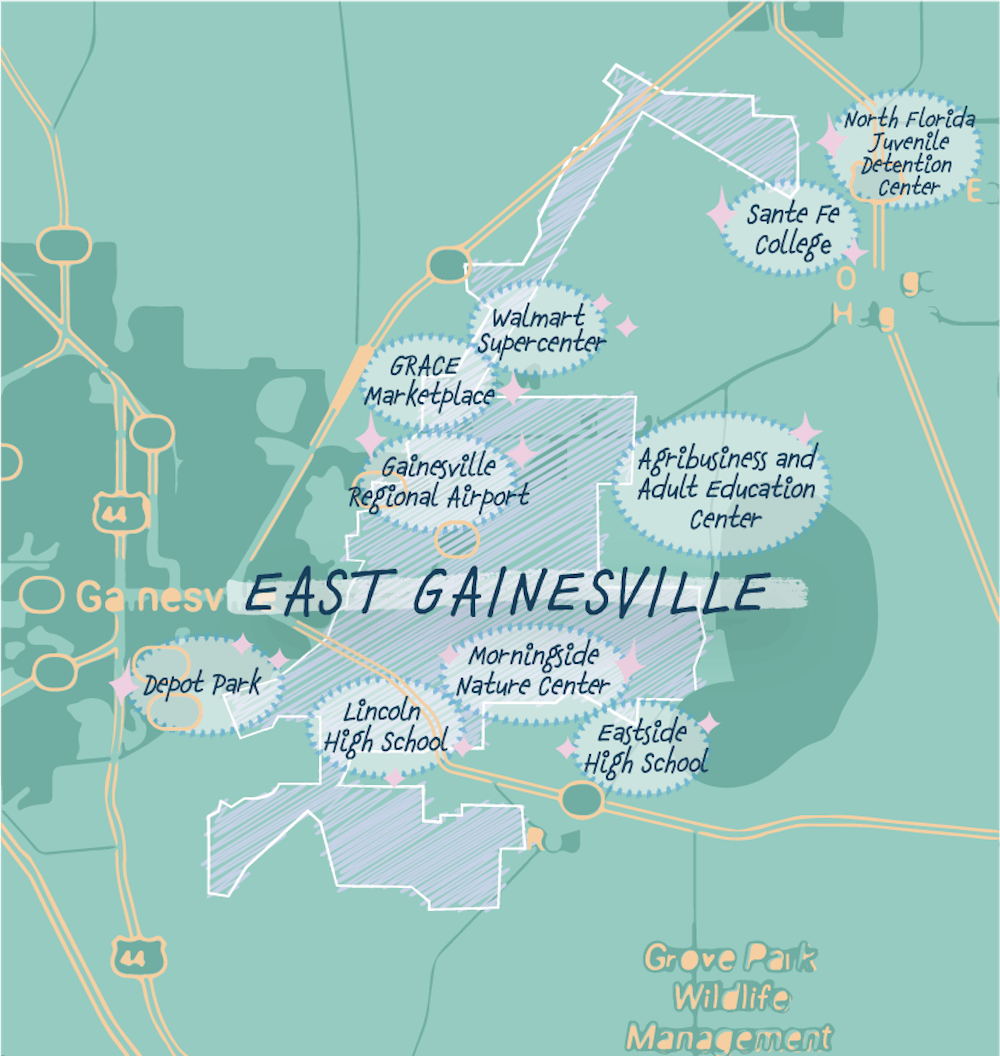

The region is known for encompassing clusters of historically Black neighborhoods, such as the Porters Quarters, Pleasant Street, Fifth Avenue and Springhill, Henry said. However, the east side of the city has lagged behind because of the west side’s development and vision of becoming a student-centered community.

Peggy Macdonald, a public historian and former director of the Matheson History Museum, said the past is key to understanding East Gainesville today.

What’s referred to as East Gainesville was really where Gainesville started out more than 150 years ago, when UF was about 17 years old, Macdonald said. Buildings with early 1800s-style architecture remain, such as the Historic Matheson House.

“The historic value of East Gainesville can’t be overstated,” she said. “It tells the story of our community and that there is something unique here.”

The Sweetwater Branch, south of Duckpond, used to be the dividing line between East Gainesville and the rest of town, she said. There seems to be a common agreement that Main Street is the dividing point, she said.

Macdonald said more white residents used to live in east side neighborhoods. As Gainesville began to integrate schools, white flight, or when white people moved out from areas that were becoming ethnically diverse, happened, and white residents moved to the west side, closer to the university.

The closing of historically Black schools, most notably that of Lincoln High School in 1970, was a significant loss to the close-knit community culture of the east, she said.

“There’s still raw feelings — a lot of pain — over how that process unfolded,” Macdonald said. “The Black community lost a connection where teachers and administrators really knew the student’s families.”

Northwest Newberry, Alachua, Hawthorne and East Gainesville have the highest concentration of Black residents in Alachua County, according to a UF study on racial inequity in Alachua County. The cities contain from 600 to up to 3,000 Black residents.

Evelyn Foxx, president of Alachua County’s chapter of the NAACP, believes that the local Black community has been treated unfairly over the years. Most residents have two jobs to support their families and have been displaced as gentrification continues to prioritize student housing over affordable housing, Foxx said.

“If you drive through Fifth Avenue, it hasn’t been the same for ten years,” she said, “All you see is student housing that takes away from its looks and culture.”

Foxx believes that there’s a lot of work left to better the future of East Gainesville.

To Foxx, affordable housing and student performance continue to be issues in the area.

She attributes the gap to a lack of adequate city and county leadership, which is why she focuses her time on getting people to vote.

“It is my belief that I can do anything, but I can’t do it alone,” she said. “It takes the community working together. Slowly, but surely we are making progress.”

Jarell Daniels, a 25-year-old East Gainesville resident and local musician known as Sky Luca$, said he hopes people will realize what the area of the city has to offer — from the Matheson History Museum to the abundance of untouched nature like the Hawthorne trail.

Daniels moved to Gainesville from Alabama when he was 11. Last year, he relocated to Duckpond, east of North Main Street, and was shocked by how different his new neighborhood was from where he lived previously in Goldview. Prior to that, Daniels attended Buchholz High School with affluent peers and he didn’t often encounter homelessness on the streets.

“It was eye-opening,” Daniels said. “It takes 30 minutes to drive from one side of Gainesville to the other. I was not aware of the community’s culture and its history.”

The young rapper decided he would learn more about East Gainesville and its history by developing a docu-series highlighting the effects of the gentrification in the area, the achievement gap between schools on the west and east side and the lack of financial opportunities for its residents. He started a GoFundMe for filming equipment and has raised $1,020 in about two weeks.

“I want people to be aware of the city of Gainesville and be proud of it,” Daniels said, adding that people are often unsure about what the city has to offer aside from UF.

To Henry, East Gainesville needs development, but developers are afraid to invest because of the area’s many low-income residents.

The Black neighborhoods in the area have the lowest per capita income and highest exposure to poverty, which is more than a quarter higher than the average, according to the UF study.

However, when Henry thinks of East Gainesville, he sees potential, remembering his childhood.

During his two terms as a city commissioner representing East Gainesville, Henry assisted in the opening of the Walmart Supercenter near Waldo Road, which was an economic boost and helped tackle the area’s food insecurity. He pushed to build the Cone Park Library Branch, which became the first library in the area.

Now, Henry has his eyes set on the Alachua County Fairgrounds, which are adjacent to the Gainesville Regional Airport. Because of their proximity, he believes building a hotel will supplement the region’s workforce and put East Gainesville on the map for travelers.

When he’s not advocating for his community, Henry plays the drums at two churches, his latest endeavor in a lifelong passion for music, which began long before his time at Lincoln High School.

“My community shaped me,” Henry said. “Even segregation didn't stop me from having a dream. All I had to do was take advantage of the opportunities that were presented to me.”

For his senior year, Henry completed his education at Gainesville High School, following the decision of Brown v. Board of Education, which called for the closing of segregated schools. There, he took a civics class with a teacher who inspired him to dedicate his life to public service.

Henry never wanted to leave the Black-owned mini marts or films at the Rose Theater behind.

“They grow up and move out of my neighborhood, but I remain to contribute and make my neighborhood better,” he said. “If everyone leaves, the power leaves with them.”

Contact Edysmar at ediaz-cruz@alligator.org. Follow Edysmar @EdysmarDiazCruz.