The story of racism in Gainesville is one of two worlds experiencing different realities for generations of black families.

A city with a large, thriving black community and a university ranked with an F in racial representation exist only miles apart.

After Gainesville desegregated in 1969, UF students continued to deal with injustices and city residents dealt with others, neither meeting in the middle together.

More than 50 years later, the rift persists. Here are stories from people who lived in the midst of racial tension and some who are trying to bridge the gap between the two communities.

The White and Higgins families

Albert White enjoyed all the simplicities of childhood growing up in east Gainesville.

He went to local shops and listened to the latest music of the ‘50s by the jukebox.

White and his friends bought drinks and snacks from his grandfather’s store. Since he was one of the only black business owners around, residents preferred to shop there rather than the white-owned stores.

Everybody knew everybody in town back then, he said. But their youthful ignorance blinded them from the harsh realities of their surroundings.

“We didn’t realize how bad things were back then because we were happy growing up,” now 74-year-old White said.

White’s grandfather Albert Higgins opened many black staples in town during the ‘50s, which included four grocery stores, a barbershop and a restaurant, White said. People knew him as Mr. Al.

White’s aunt, Barbara Higgins, discussed the work ethic of his grandfather in a 1992 interview with the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program.

Albert Higgins would keep his stores open as long as possible because he loved interacting with the community and earning his living, Barbara Higgins said.

“He wanted to make another dollar. That was his life,” she said in the interview. “He would never close up.”

Later in her career, Barbara Higgins became the first black professional to work in the Alachua County Courthouse. In 2019, the Alachua County Commission declared Feb. 2 as “Barbara L. Higgins Day” in honor of her community service.

White said that while he was finishing his studies at North Carolina A&T State University, his wife applied for a social work job with the Greensboro Health Department but was turned away when she arrived. This incident made them advocates, and they vowed to help African Americans in the community who may face similar struggles.

White proved to be following in the footsteps of his aunt as a community pillar when he and his wife, Ora, were celebrated and given awards at the Springhill Baptist Church in 2017.

Originally, the two refused the honor for fear that it would overshadow the great work done by other community members.

“What we do, we don’t do it to be recognized. We do it because we care about people,” White said.

Growing up during integration

Rodney Long grew up in the same community as White and the Higgins family, but his memories of the past are riddled with violence.

Long, born in 1956, founded the Florida Martin Luther King Jr. Commission 35 years ago to advocate for the black community. He grew up in the Porters neighborhood behind Depot Park until his family moved to northeast Gainesville when he was 8.

Violence, caused by the neighborhood’s own residents, plagued the community nightly, Long said. Long attended Lincoln High School until he was forced to integrate into Gainesville High School in 1970.

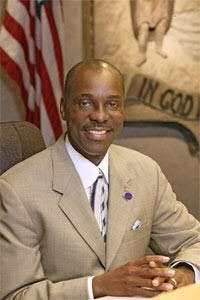

Rodney Long

“When I went from an all-black high school to a white high school, culturally, it was night and day,” Long said. “We didn't understand their culture. They didn't understand ours. Yet, the law said that we needed to be together.”

Long said that the hostile environment at school kept black students from attending. Their educations suffered. They felt like they weren’t wanted, the teachers or the students.

“We’d rather be in town than there,” Long said.

When a white school got new textbooks, their outdated textbooks were given to the black schools, Long said. He added that those hand-me-down books prevented them from learning about black history.

A major piece of history was missing from their books.

The Rosewood Massacre occurred in 1923 in Rosewood, Florida. Nearly 200 black people were murdered by KKK members in Gainesville and residents from the surrounding counties.

As a child, Long’s family never discussed the massacre. Long knows residents who were alive at the time of the massacre who still refuse to talk about it. But he is relieved that more people are learning about Gainesville’s black history, he said.

“Whenever you can begin to discuss some of the racial injustice in your community, it begins the healing process,” Long said. “We got to understand that there is a way for us to improve and that way for us is for us to be concerned about our own and our own survival and economic prosperity,” he said.

Present-day actions

When Rahkiah Brown moved to Gainesville, she realized youth in the area didn’t have the ACT-SO program she grew to love in high school.

The ACT-SO, or Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics program, is an academic mentor and mentee program for black high school students. As a high school student in Fort Lauderdale, Brown was an active mentor for children through her local NAACP chapter.

Once Brown, 31, moved to Gainesville in 2006, she created a local ACT-SO program and began coaching and mentoring black youth to attend local academic competitions.

That year, Brown’s ACT-SO students made it to the national level. They went from their Gainesville neighborhoods to seeing Stevie Wonder walk out of a Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles in Los Angeles. That day is something she and all her students have remembered, Brown said.

Brown said her time on campus felt like only a handful of students were active in the community. She felt like there weren’t many ways on campus for students to truly learn about Gainesville’s history with racial disparity.

She hopes that the small number of black students involved in the community will increase so the children in programs like ACT-SO can feel represented by those who are helping them.

“When I was a student, there was a lot I had to learn by getting involved,” she said.

Mackintosh Joachim, a 20-year-old UF finance and women’s studies sophomore, is the current president of the UF NAACP chapter.

Joachim said the UF NAACP chapter started a free breakfast program in February where chapter members go to the Porters neighborhood to feed 4- to 12-year-olds and teach them about black history and identity.

Mackintosh Joachim

Joachim said he feels as though the black students attending UF are in competition with each other and do things to be recognized. He said that although some black students are aware of the disconnect between the UF and Gainesville black communities, the strict involvement culture on campus keeps students focused only on the university.

“We tend to forget about the greater good and the bigger picture,” Joachim said. “UF will never become number one if our black community is still stagnant.”

The ruins of a home destroyed during the Rosewood attack, avenging the alleged murder of Fannie Taylor.