They didn’t build her a hut.

Anna Prizzia had traveled 8,000 miles across the world as a 27-year-old Peace Corps volunteer to help the villagers of Port Resolution, Vanuatu, grow a stable economy with their natural resources. And they didn’t build her a hut.

Despite the Peace Corps’ hesitations and the village’s broken promise to build a place to stay, Prizzia zealously chose to shelter in a temporary shack near the village. There, she was surrounded by swaying palms, idyllic bays lapping on black sands, a looming active volcano and vibrant ni-Vanuatu neighbors. She began building relationships within the community –– and a real home.

For months, she wove palm fronds into a roof for her hut. Many of the villagers stood by and watched, and soon, Prizzia’s frustration boiled over. She asked Papa Samson, the head of the family who cared for her, to call a meeting. She observed the 200 ni-Vanuatu she now considered friends, and they observed her back. She felt their stares on her sun-bleached hair, freckled skin and blue eyes. She felt like the outsider that she was, and she couldn’t hold back her tears.

“I came all across the world, left my family and my friends and everything I knew to be here,” Prizzia sobbed. But now, she needed help.

The next day, the villagers finished building Prizzia’s hut. And they built her a bathroom.

It occurred to Prizzia later that maybe the villagers just didn’t know she needed their help. After all, she never asked. When she chose to be vulnerable, the villagers listened. Prizzia learned she needed to listen, too.

She came to Vanuatu with good intentions, but she learned that strengthening the community could not come solely from an outsider. To succeed, she had to create a partnership. She needed to be who they wanted her to be, not who Prizzia thought they needed.

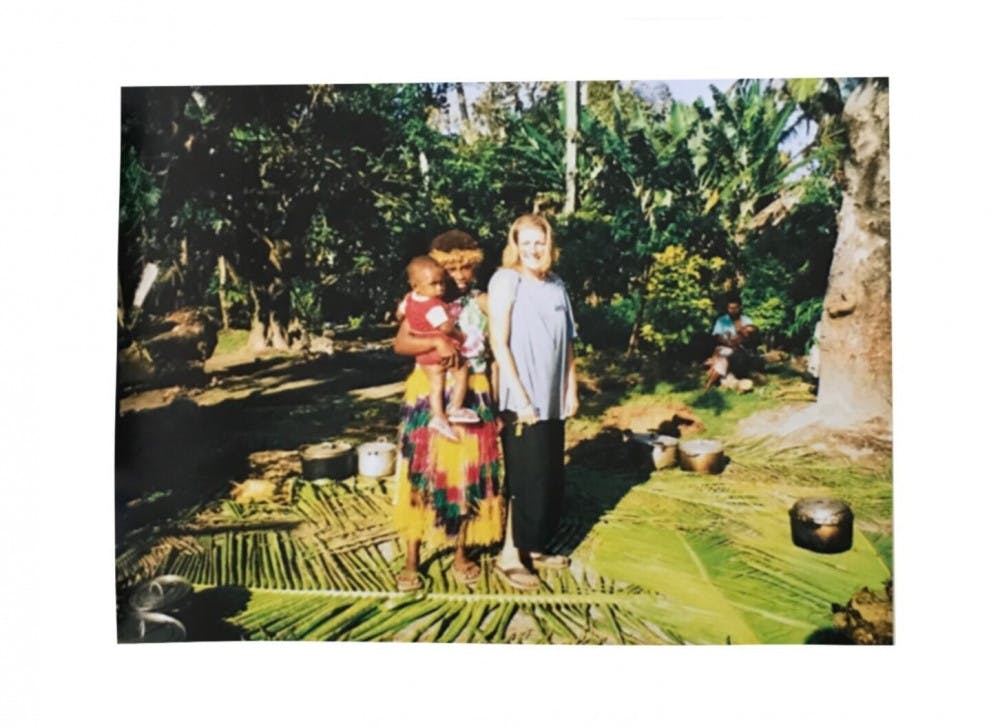

Prizzia’s “sister” Gel and women in her family pose for a picture on the pristine beach of Port Resolution. Eco-tourism is one of the main ways this community supports its economy. “Momma” Jenna and “sister” Gel helped Prizzia collect materials to build her hut in Vanuatu. Gel’s father, “papa” Sampson called the village meeting that convinced the villager’s to trust Prizzia’s intentions, eventually allowing her into the community.

Soon, the villagers told Prizzia they wanted to solidify a way to sell their crafts. She trained the women of the village in bookkeeping while the men labored on a new marketplace. And even when the tourists didn’t visit, the village used the building as a market, trading food and goods with one another in a centralized place.

The villagers in Port Resolution were tied to their culture, and they were tied to each other. Because valuing each other was a part of their culture. Together, they had immense power to better their community. They trusted each other to be vocal about their needs so others could lend a helping hand. Prizzia never experienced anything quite like it in America. What would this kind of community look like at home?

At the end of her service, Prizzia returned to Gainesville with fellow Peace Corps volunteer, Nick Taylor, who soon became her husband and father to their daughter Nora. She also returned with determination to make her new home a better place to live.

In Gainesville, Prizzia started building her family. And, she started building a community.

Food as a gateway drug

On her first trip to a grocery store after her return from Vanuatu, Prizzia stood under the harsh glare of fluorescent lights, surveying her options. Rows and rows of cereal stared her down. In the next aisles, grains, produce, milk, meats of every cut and fish from every ocean. So many different brands of chips, soups, sodas.

How is it possible we have all of these choices? she thought.

Back in Vanuatu, she had carried the water she needed and picked by hand the food she ate. In Gainesville, she suddenly had everything she could ever want, as long as she had the money to buy it.

Prizzia returned to Gainesville wishing to craft a community much like the one she had experienced in Vanuatu. The city had already felt like home, though she originally only came for graduate school.

She grew up in Virginia and Connecticut and attended the University of North Carolina in Wilmington before graduate school at UF. With her bachelor’s degree in marine biology and her master’s degree in wildlife ecology and conservation, Gainesville was a perfect base, she said. She fell in love with the city in a way that many of its ephemeral students don’t. She was taken by the trees, swamps and prairies. She was amazed by the wealth of natural resources so close to home.

But that first day in a supermarket, she realized that despite the abundance, resources were not distributed equally. She realized how abundant food was for those who had money. And, how much of it went to waste, even though there were plenty of people in need.

In Gainesville, she took up a new mission. In many ways, it was no different than the one that drove her in Vanuatu.

She was a young mother of means and even she noticed the lack of options for fresh, healthy food. She wanted to have relationships with local farmers, to learn about how her food was produced, but there were few Community Supported Agriculture farms and restaurants that prided themselves in serving farm-to-table. If she was having trouble finding good food, what must it be like for the less fortunate?

UF makes up almost a quarter of Alachua County’s population. The non-university residents, especially those who are lower on the income scale or live in rural areas, are often forgotten, Prizzia said. Gainesville itself is split by Main Street. On the west side of town, there are over 15 bustling grocery stores with fresh products. In the east, there’s one Walmart. The USDA classifies all of east Gainesville as a food desert, an area in which residents lack access to affordable, fresh and nutritious food.

In fact, Alachua County has the fourth highest food insecurity percentage in the state at 19.8 percent. The county’s poverty rate is 17 percent for white residents, 5 points over the state average. Among Black residents, that number almost doubles to 31 percent, increasing the racial divide.

Prizzia set herself on a path to bridge the gaps. She thought, if she could get people to care about their neighbors, she could sow the seeds for a functional community like the one she had experienced in Vanuatu. And the divides, she believed, would begin to shrink.

Food opened the way for Prizzia’s activism in Alachua County. It was not just fuel but a way to connect, congregate and communicate ideas. It became Prizzia’s gateway drug to sustainability –– not everyone will want to talk about waste or protecting the environment, but everyone needs to eat.

After leaving her job with the county’s water management district in 2006, Prizzia started working for UF. They had the power and resources, she says. And she still had her dreams.

Step one: help create and then direct the Office of Sustainability. Now she had the sway to suggest and work on projects.

Step two: transform an overrun field on campus into a community garden. From 2014 to 2016, Prizzia dug in the dirt with students and scientists, planting seeds and raising rows of collards, kale and squash near the banks of Lake Alice.

Step three: use the fresh produce to supply a pantry on campus for those without reliable access to food.

Step four: become the campus food systems coordinator, her current role, in which she oversees the Field and Fork campus food program, the UF community farm and the pantry.

At the same time she arrived back in Gainesville, Prizzia met Melissa DeSa, who admits she was more comfortable working with plants and animals than with people. But that was before she met Prizzia, whose love of community was infectious. In 2006, the two women launched a chapter of Slow Foods USA, a global nonprofit that operates in 60 countries and has 150 chapters in America. Its goal is to help create strong local food systems.

But Prizzia and DeSa did not stop there. They created Forage in 2012, which acted as a seed bank and food education group. Anyone could come and buy seeds and learn how to cultivate them in their home gardens or commercial farms. Then they went even further and merged Forage’s seed bank with another group, Blue Oven Kitchen, which worked to help chefs and restaurants gain footing.

That’s how their current venture, Working Food, was born. The group aims to connect farmers with local markets, restaurants and other businesses to help grow a robust local food system.

In Port Resolution, the village’s close connection inspired Prizzia. She was struck by how they listened to each other’s needs and worked together to find solutions. She used to dream of what that would look like at home.

In Vanuatu, one family primarily took care of Prizzia. Here, she and her “sister” Gel commemorate Gel’s first Sik Mun, a ni-Vanuatu tradition for a women’s first menstruation. The whole community takes part in a ceremony to mark the occasion.

Prizzia had come a long way from Vanuatu.

It has been 15 years of hard work –– she is always on the move. She ties her blonde hair, now dyed to hide grey, in a ponytail and wears a uniform of jeans and a blouse, which she said is “dressed up enough to show up at a meeting and dressed down enough to go to the farm.”

She said she is ready to take another step in her mission to create a local food system. This one involves policy.

Last year, she heard through the grapevine that Robert “Hutch” Hutchinson was retiring from his position as the chair of the Alachua Board of County Commissioners. That would leave the District 3 seat open. Prizzia looked up to Hutch after his three terms as commissioner. She thought he was honest and that he backed up his beliefs with actions. That was her idea of what a commissioner ought to be.

She envisioned the Hutch-sized vacuum that would be left after his retirement. And felt a calling.

Prizzia’s knew a political campaign would be difficult. In the upcoming Aug. 18 primary, she’s running against Democrats Kevin Thorpe, senior pastor of Faith Missionary Baptist Church, and William Jason Stanford, a teacher at Hawthorne Middle and High School. If she wins, she will face Republican Joy Glanzer, a Newberry commissioner and real estate agent, in November.

Someone had to champion equity and economic justice issues, she thought. That someone needed to be collaborative and determined enough to get things done in an era of deep polarization. She believed she could be that someone.

Chopping veggies, talking politics

I first caught up with Prizzia one evening in early April. By then, COVID-19 had already changed the world, and Prizzia was facing the prospect of running a political campaign from her home.

I had hoped to spend some time with Prizzia. Instead, she put me on speaker phone as she washed her hands for the recommended 20 seconds and chopped the vegetables that would accompany a roasted chicken for dinner.

Her family, like everyone else, were getting accustomed to their new normal. Daughter Nora, 11, was graduating from fifth grade at home. Husband Nick, a data analyst, was on the computer in his empty office. And Prizzia was trying to figure out how she could get elected without shaking hands, taking pictures and discussing community-based decision-making with constituents.

She had practiced canvassing with her friend, Gainesville Commissioner Gail Johnson, who was thrilled about Prizzia’s campaign.

“She pays attention. She’s gonna know exactly what to do and how to do it because that’s just the person she is,” Johnson said.

And similarly, supportive, Hutchinson had plans for a little soirée to kick off Prizzia’s spring campaign and help raise much-needed money. Prizzia’s research showed that it took $50,000 to run an effective campaign in Alachua County. But the pandemic put an end to those plans. Now, her campaign was not only difficult, but it also felt “weird.” She could no longer do what she did so well: connect with people, up close and personal.

Prizzia’s mind races while she chops veggies at home. She’s toying with new ideas for a future filled with Lysol and face masks. Emailing lists and social media, she knows, will quickly become her new best friends. She’s hoping voters who are increasingly online will research her record and see the work she’s done for the past two decades for her major platform points: environmental protection, social justice and equity and building the local economy.

Prizzia sees the pandemic as a possible opening. What has worked best, she said, are community efforts to help people in this strange and difficult time.

For example, in the middle of quarantine, nationwide protests thrust the Black Lives Matter movement and police and prison reform to the forefront of America’s collective psyche. Thousands of people risked their health to protest the deaths of unarmed Black people and demand an end to systemic racism. Many quarantine dinner-table conversations gained an entirely new vocabulary.

But even before the nation erupted in anger, Prizzia had told me her own reformation ideas.

In Alachua, Black people make up only 20 percent of the population but more than 70 percent of the incarcerated population.

Prizzia envisions the construction of a center that offers resources to those who disturb the peace, instead of arrests and jail time. Such a center, she said, could offer substance abuse or mental health counseling, connect vulnerable people with justice system representatives and redirect any necessary punishment to community service.

Prizzia said the time is right to implement big changes, given the current climate. On a community level, the county has stepped up to feed the hungry, to pay the rents, to keep everyone safe amid the pandemic. It has forced Alachua County to take a good hard look at whether the systems in place are working. Strangely, the pandemic, she said, may just be the catalyst that was needed to bring change.

Those who already struggled are struggling more, but even people who never once thought about where their next meal would come from are getting more involved, Prizzia said. Some are growing home gardens, and others learning how to bake bread for the first time. The grocery store, once a weekly visit, is now a daily social hour. Food is the common denominator between people.

Prizzia thinks that if people can learn about the food they eat –– where it’s made, how it’s produced, why it takes time to get to them –– then they can learn more about each other, too. That’s the first step to the kind of trust that can transform a community.

What’s a few blueberries worth?

On one mid-April day in quarantine, Prizzia was back to her day job of trying to help straighten out kinks in the local food system.

The summer’s heat had not yet set in as Prizzia headed out to Working Food to pick up 244 cases of blueberries grown at a local farm. The farmer lost his contract in the pandemic shutdown, and pounds and pounds of fresh blueberries were threatening to go to waste. Prizzia cringed at that thought. Those blueberries rotting in the field were just another symbol of the wastefulness of an ineffective food system.

She and DeSa reached out to their community contacts, posted on social media and found a market. They used some of the blueberries in the Working Food meal package program, which, since the beginning of April, has safely delivered healthy meals to over 15,000 individuals who have been unable to get reliable food throughout the pandemic. They used some of the blueberries at their bi-weekly drive-through farmer’s market, where Alachua residents can order fresh produce ahead of time straight from the farmer. The rest were allocated to the chefs in the Working Food kitchens, who have been able to stay afloat during a period of economic hardship with financial support from the Working Food community.

But it’s not just blueberries that are getting tossed. This kind of wastefulness is happening all over the country, Prizzia said. And it’s the antithesis to everything she has ever worked for. Farmers are dumping milk, plowing over beans and cabbage crops and smashing eggs. Literally, tons of perfectly good food –– destroyed simply because there is no transportation network to get the food to the consumer. Meanwhile, others are starving as their previously affordable options like canned goods fly off the shelves to stay in panic bunkers.

Prizzia knows the pandemic will give way eventually. But the waste? It will not end, she said. Farmers have had to deal with contracts dissolving for years, and without a local distribution network, throwing away their crops is the only option. That’s why Prizzia wants to shorten the chain. Having a strong local food system means security. You don’t need to rely on any outside forces to get your community what it needs.

In the South Pacific, Prizzia had discovered what can happen when people feel connected. There, she was the outside force, trying to ascertain what an unfamiliar community needs to thrive. She could only truly understand what they needed once she listened, trusted, became a part of the whole.

At home in Alachua, Prizzia stands firm on what she learned all those years ago: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. She believes that now, as she makes her first run for public office, more than ever.