Young adults tend to fumble. Some drop a class; some get busted for marijuana or fake IDs. For the latter, former State Attorney and Florida Sen. Rod Smith introduced a still-thriving solution in the early 1990s: deferred prosecution agreements, or DPAs.

A privilege offered to first-time offenders of nonviolent crimes, DPAs are a contract between a defendant and the State Attorney's Office to complete community service hours or donate to selected nonprofits in exchange for dropped charges.

Many of these offenders are college-age, especially in Gainesville, where college students make up a significant portion of the population, Smith said. He wanted to avoid giving them a criminal record that would hurt job applications, professional school admissions or whatever their future holds, he added.

“We thought it was a good way to avoid criminal prosecution,” Smith said, “but with people understanding that this is your chance, you know you made a mistake, this is the way we're going to deal with it.”

Breaking the cycle

Donations are made directly to charities, and offenders must submit proof of their contributions to the state attorney’s office. This is intentional so the Florida government never receives or handles the money, which Smith said could otherwise lead to concerns of transparency.

“It was a way to deal with moving cases along pretty quickly that don’t need to clog up the system,” Smith said. “And it served another purpose… to allow people to have a clean record.”

The impact of deferred prosecution extends beyond the individuals who receive a second chance. It also strengthens local organizations that serve the community’s most vulnerable.

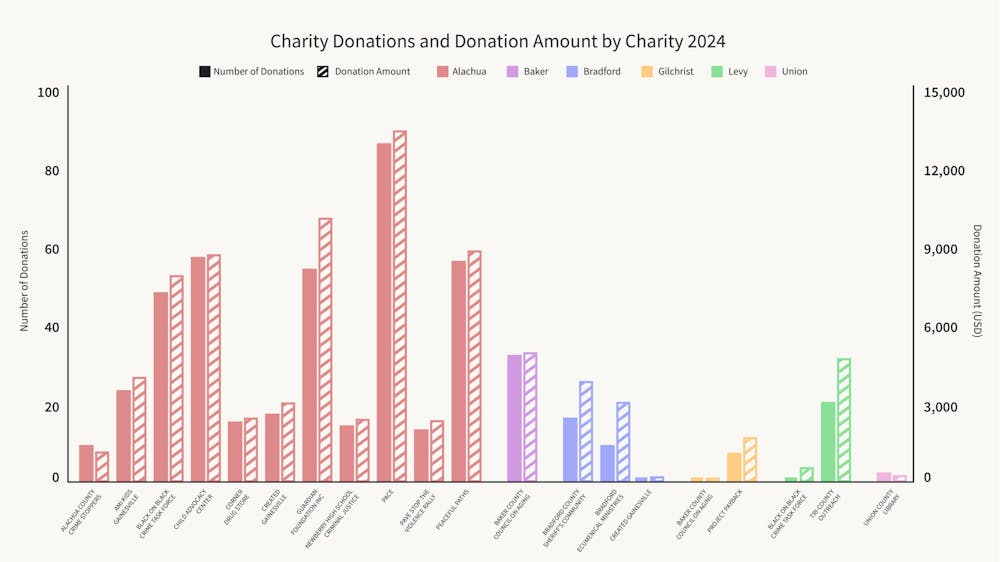

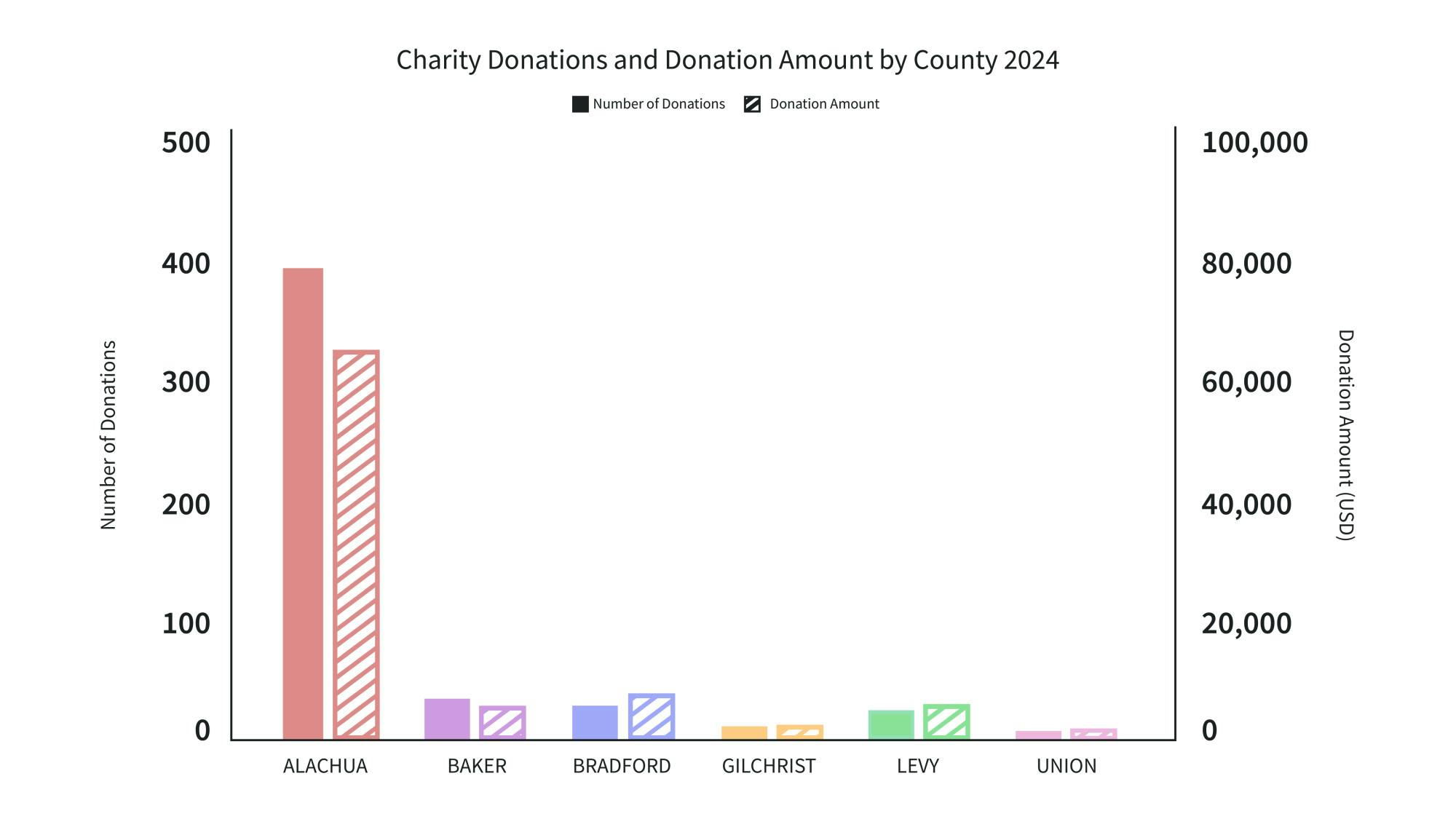

In Alachua County, 11 charitable organizations benefit from these donations, which help fund services for at-risk youth, children in foster care and victims of domestic and sexual abuse.

One of the first nonprofits to be included on the list for DPA donations was the Child Advocacy Center (CAC) in Gainesville, founded 25 years ago by Smith and his wife, DeeDee. After visiting a similar operation in Daytona Beach, Smith decided to create one for Gainesville.

The CAC provides critical services to children who have experienced abuse, offering forensic interviews, therapy and advocacy to help them heal. The center works closely with law enforcement, the Department of Children and Families, therapists, victim advocates and the State Attorney’s Office to ensure cases are handled with care.

“People who come from homes where there has been violence tend to go into homes and become violent,” Smith said. “That’s what they learned, so we were trying to break that cycle.”

Keeping the lights on

The CAC has been a recipient of deferred prosecution donations for over two decades, providing a steady, albeit small, stream of funding helping sustain its mission.

While the center operates on an annual budget of nearly $2 million, CEO Sherry Kitchens said DPA contributions, ranging from $8,000 to $12,000 per year, play a crucial role.

Although it’s a small part of the nonprofit’s budget, it’s an important one because the funds are unrestricted, Kitchens said.

Unlike grants, which often come with strict stipulations on how the money must be used, these court-ordered donations go directly to the center, allowing administrators to allocate the funds where others leave gaps.

The CAC also receives state funding and pass-through grants throughout the year. The funds, Kitchens said, help bridge the gap between the critical services the CAC provides and the operational needs keeping the center running.

“A lot of grants want to fund direct services to children, which is amazing,” she said. “But we also have to be able to keep the lights on, and pay for the internet and pay for maintenance.”

Each nonprofit in the DPA list is assigned a portion of the alphabet, and donations are directed based on the last names of defendants who are ordered to contribute. This system, she said, means the CAC cannot actively influence or increase the funds it receives.

Transparency, Kitchens said, is a priority in handling these donations. When individuals make court-ordered contributions, they must provide their case number, and the center issues a receipt along with information about its work.

When Kitchens first joined the CAC in 2005, the center was struggling financially and served only about 250 children a year. Last year, it helped 3,964 victims.

Kitchens sees DPA contributions as more than just financial support, but also as a restorative process for the offenders.

“This program gives folks who have made a mistake an opportunity to do something good,” Kitchens said.

Consistency and support

Peaceful Paths, a Gainesville-based domestic violence center, also benefits from court-ordered donations under the DPA program.

Peaceful Paths provides emergency shelter, legal advocacy, counseling and support groups for survivors of domestic abuse. With the help of the DPA program, the nonprofit can step in when survivors face financial barriers that traditional grants cannot cover.

The crimes and cases tied to donating offenders remain anonymous, according to Erica Merrell, Peaceful Paths’ chief financial officer.

Although these funds represent less than 2% of Peaceful Paths’ fundraising budget, Merrell said their impact is significant. Like at the CAC, the majority of funding at Peaceful Paths comes from state grants, which are restricted, unlike those from DPAs.

“There are times that grants will not pay for child care that is past due,” Merrell said. “We tap into funds like this in order to make really significant changes in a survivor’s life that is probably not covered by federal or state funding.”

Peaceful Paths has been a beneficiary of DPA donations for more than two decades.

Like the CAC, Peaceful Paths ensures full transparency in the use of its court-ordered donations. As a state-certified domestic violence shelter, it undergoes routine audits and financial reviews to ensure compliance with funding requirements, Merrell said.

In 2024 alone, Peaceful Paths provided over 56,000 services to survivors of domestic violence.

While the Child Advocacy Center and Peaceful Paths use deferred prosecution donations to support survivors, AMIkids Gainesville focuses on prevention and helps at-risk youth build stable futures.

The nonprofit, which serves young people ages 11 to 21, offers workforce development programs designed to prepare them for careers, apprenticeships or higher education. While it receives federal funding through the U.S. Department of Labor, court-ordered donations provide flexible, unrestricted support.

“These court-ordered donations help us to make experiential education opportunities available to the youth at AMIkids Gainesville,” Roxane Wergin, senior director of marketing and communications, wrote in an email.

The funds contribute to four “Challenge” events per year — Winter, Summer, Marine and Wilderness Challenge — where participants engage in hands-on learning experiences designed to build leadership and teamwork skills. DPA contributions have also helped fund a student-run cook-off contest for those earning ServSafe certifications and a Program Store, where youth can exchange earned tokens for essentials like snacks, clothing and personal care items.

Like the other nonprofits on the DPA donation list, AMIkids Gainesville depends on a mix of funding sources, but the flexibility of court-ordered donations allows them to step in where grants fall short. Whether supporting career readiness, life skills, or personal development, these funds reinforce the same principle that DPAs were founded on: turning an offender’s mistake into a helping hand for the community.

Contact Vera Lucia Pappaterra at vpappaterra@alligator.org. Follow her on X @veralupap.

Vera Lucia Pappaterra is the enterprise race and equity reporter and a second-year journalism major. She has previously worked on the university desk as the university general assignment reporter. In her free time, she enjoys deadlifting 155 lbs. and telling everyone about it.