With Florida’s watermelon growing season in full swing and blueberry season not far behind, migrant workers begin their routes of seasonal work throughout the counties of north central Florida. They do not come alone, however — their families that depend on the income these jobs provide accompany the workers as they migrate.

For the children that follow their families from county to county and state to state, constant migration can have detrimental effects on their educational attainment, according to Victoria Gomez de la Torre, the 63-year-old program supervisor for the Alachua Multi-County Migrant Education Program.

With Florida’s watermelon growing season in full swing and blueberry season not far behind, migrant workers begin their routes of seasonal work throughout the counties of north central Florida. They do not come alone, however — their families that depend on the income these jobs provide accompany the workers as they migrate. For the children that follow their families from county to county and state to state, constant migration can have detrimental effects on their educational attainment.

Gomez de la Torre said this program aims to meet the needs of the kids both in education and areas that may impede their development if mishandled, such as nutrition and health.

“You can't tutor or educate a child who does not have food in the house, who is sick, who has issues,” Gomez de la Torre said. “We try to provide referrals to medical services, referrals to social services and then obviously focus on the academic needs.”

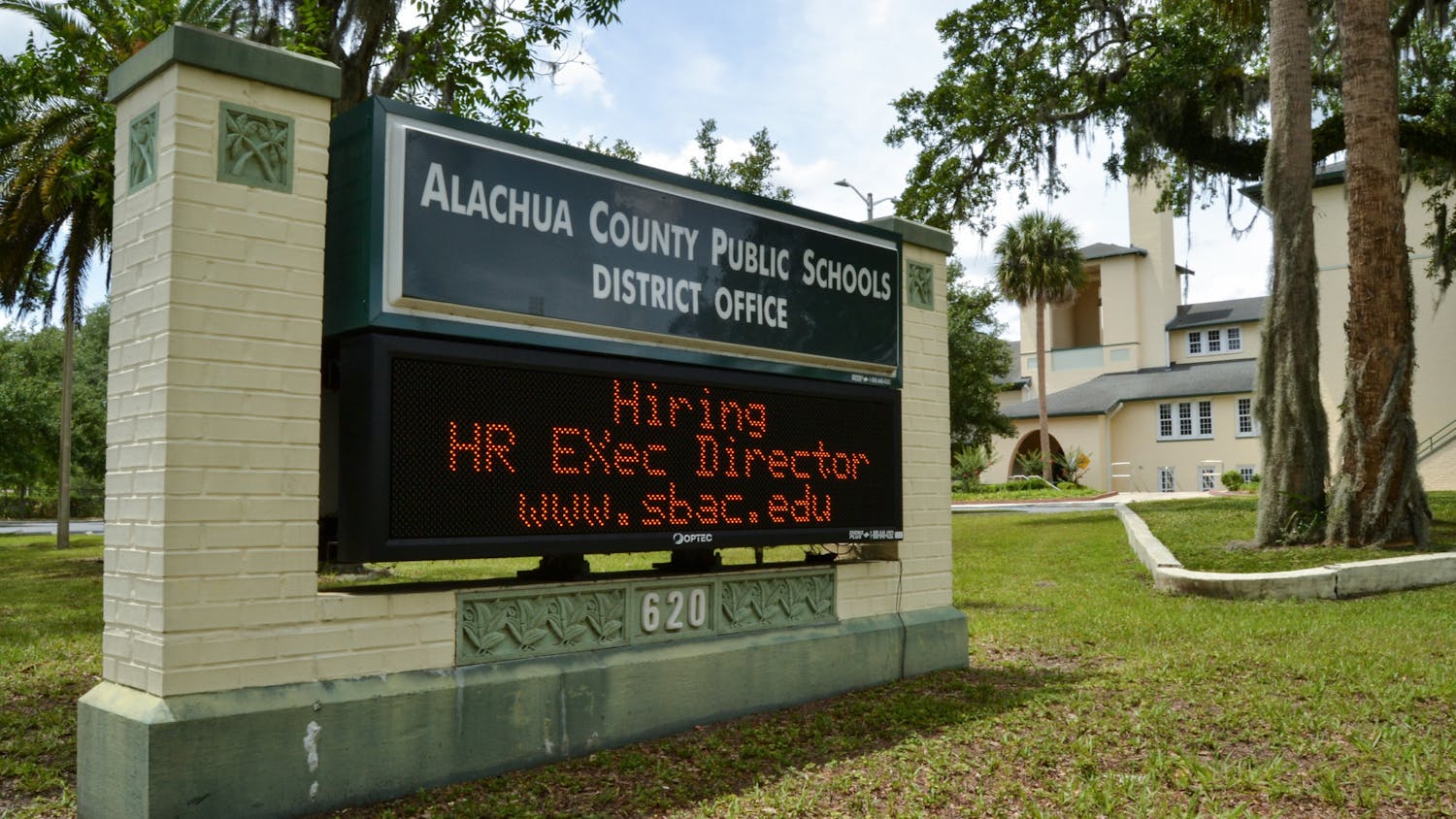

Since the federal government created the MEP nationwide in 1966, the program has evolved in north central Florida as a consortium of 13 counties, including: Bradford, Citrus, Clay, Columbia, Dixie, Flagler, Gilchrist, Hamilton, Levy, Marion, St. Johns and Union. A similar collection of counties also serves the Florida panhandle, though the Alachua Multi-County consortium is the largest in the state.

The program identifies potential migrant families during school registration. If a family writes down an occupation as related to agriculture, fishing, dairy or food processing, then those families get referred to Gomez de la Torre, who conducts interviews and questionnaires to see if they qualify as the population they serve.

“Our program is the one that determines if a person qualifies for a program or not,” Gomez de la Torre said. “It’s not up to the school to decide, ‘Oh, he came from Mexico or Venezuela, so he's a migrant.’ He might be an immigrant, but to qualify for the program there's a specific criteria as to what they do.”

According to the Alachua MEP website, a migratory child is defined as one who is “under the age of 22 without a high school diploma, who moved, either on his/her own or with a parent, guardian or spouse across district/state lines in the last 36 months for the purpose of obtaining/seeking temporary or seasonal employment in agriculture, fishing or food processing activities.”

Gomez de la Torre said one of the challenges for Latin American immigrants was the role of the parents in education, especially for immigrant workers who culturally have a different idea of how schooling works.

“In Latin America, schooling is the responsibility of the school,” Gomez de la Torre said. “So the family's job is to put food on the table and a roof over their heads and the teacher's job is to educate the kids … We try to make them understand that here it’s about 50/50, you have to be super involved in their education.”

While many migrant agricultural workers tend to be Hispanic immigrants, Laura Ritonia, the program’s 62-year-old academic coordinator for middle and high schoolers, said the MEP is not the same as the English Second Language program and maintained that many MEP beneficiaries are not immigrants at all.

“A large population of our students are our white Americans, and their families work in fishing,” Ritonia said. “So, in Citrus County and Levy County … we have several kids that are in school, but they have interruptions to their education due to the fact that they’re getting on the boats and crossing district waters.”

Ritonia said the MEP is important for this population of children because they tend to have tumultuous educational histories. Some children may pass through three different schools in a given school year, she said.

“Our students are higher risk of not graduating or getting through school,” Ritonia said. “Typically they’re lower economic households, and then of course, the disruption of their education … We see kids that are coming into the country that may have finished school in third grade, but they're at the age where they should be in eighth.”

Ritonia also said the program keeps track of the children as they migrate between MEP consortiums, whether within or out of state.

“We had a student we just found out that he had left Hamilton County and went to Madison County,” Ritonia said. “He's a young man that we're concerned about. He's in 11th grade, so I just left a phone message asking him to call me to make sure that [he’s] enrolled. We follow our kids.”

Since the coronavirus pandemic, the largest problem shared by both primary and secondary education appears to be missing out on school, with truancy being the largest problem among middle and high school students, according to Ritonia.

Edith Sanchez, the program’s 61-year-old academic coordinator for pre-K and elementary schoolers, said the program worked in close collaboration with schools.

“We cannot provide services without the permission or the authorization with the schools and the teacher,” Sanchez said. “So, we need to work very closely with the teachers. And they determine what the academic needs are to work with the kids.”

Beyond being an academic coordinator, Sanchez is one of the program’s tutors. She visits families to help the parents engage with their children, providing them flashcards and activities to maintain interaction throughout the week.

Sanchez also helps with medical tasks that for an American family may seem mundane but for a migrant family can be confusing.

“It’s part of our work to explain to the parents how the processes are,” Sanchez said. “Maybe the parents need to know how to schedule an appointment with the doctor … how they can write an excuse if the student is sick at home.”

The MEP has seen many success stories. Ritonia, the academic coordinator for secondary education, said three students who graduated from their program were accepted into Muhlenberg and Lafayette colleges. Many more have stayed in Gainesville and went to Santa Fe for their electrician and HVAC apprenticeship programs.

“That’s my goal,” Ritonia said. “To get them out of school, graduated and into post secondary or something that’s meaningful for them and for the community.”

Contact Eluney Gonzalez at egonzalez@alligator.org. Follow him on X @Eluney_G.