Every year, the “Manatee Capital of the World” erupts in celebration for a weekend-long festival. Yet even as thousands gathered this year to celebrate the manatee, the species struggles to overcome human threats.

More than 25,000 people packed into downtown Crystal River Jan. 13-14. Vendors sold everything from manatee-shaped soft pretzels to art depicting native sea life, and venture groups offered tours by boat or kayak to see manatees in their natural habitat.

One booth offered the chance for people to adopt their own manatee.

In exchange for donations, the Save the Manatee Club offered adoption certificates and manatee memorabilia. As a 501(c)(3) non-profit, the club focuses on protecting manatees in Florida, even as the species faced steep challenges in recent years.

Gina McClain, the organization’s outreach and volunteer specialist, said the festival is an opportunity for Save the Manatee Club to garner financial support and teach people how they can help the species. Many festival attendees come back to the club’s booth year after year, McClain said, while others are excited to learn about manatees for the first time.

“People are incredibly generous,” she said. “They love manatees. It’s everybody’s favorite mammal.”

Florida’s manatee population has struggled over the past few years, leading many petitioners to call for its re-entry to the endangered species list. In 2017, the manatee was reclassified from “endangered” to “threatened” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Save the Manatee Club filed a joint petition in 2022 to put the Florida manatee back on the endangered species list.

The decision to remove the manatees from the endangered species list was premature, Save the Manatee Club Research Associate Cora Berchem said. Due to the challenges manatees face, it’s important that they have as much protection as possible, she added.

Over the past few years, manatees have experienced an increased mortality rate. In 2021, the number of manatee deaths nearly doubled from 600 to 1,100, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

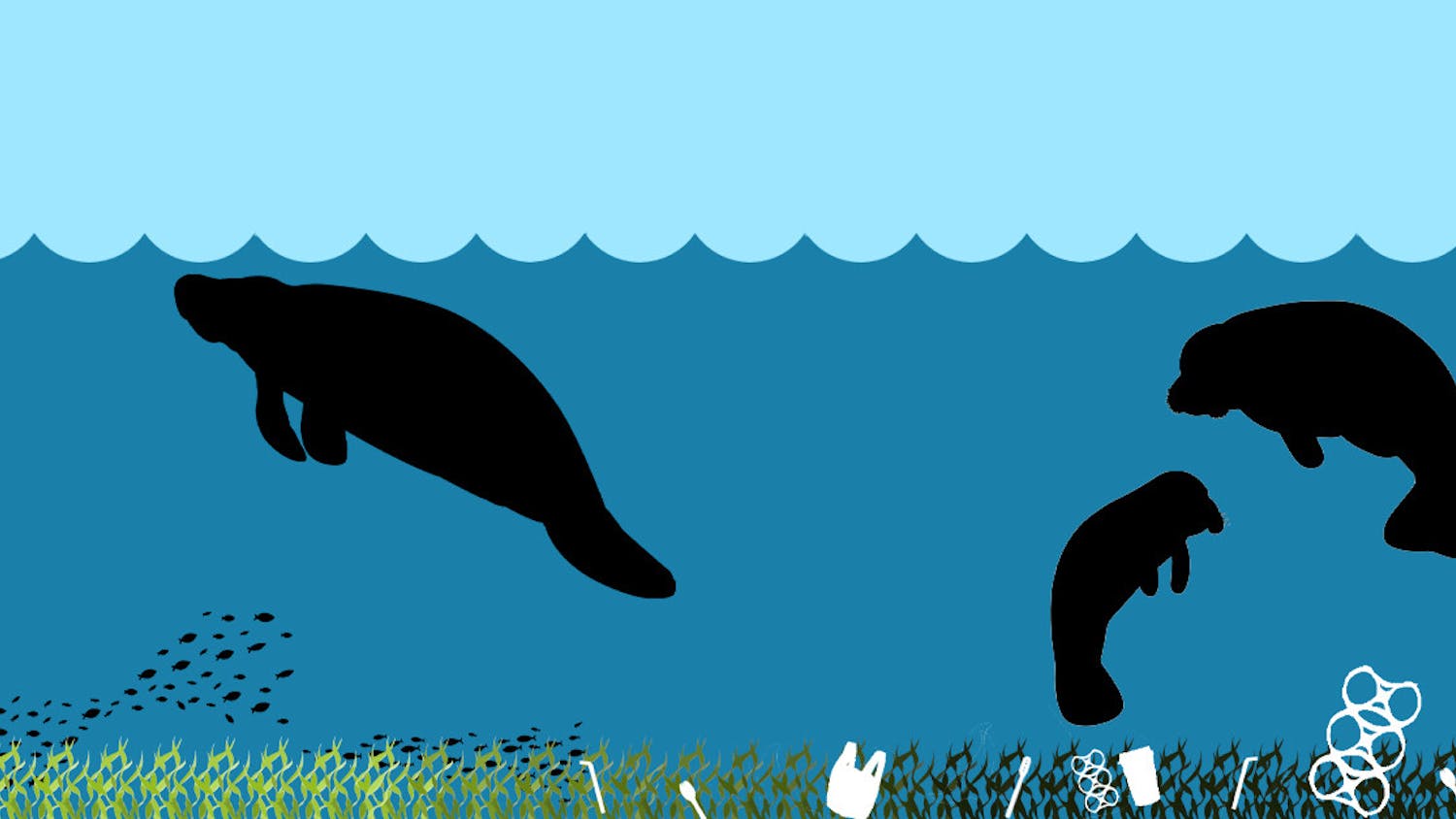

This increase was due to a mass die-off of seagrass, the main food source of manatees, Berchem said. Heavy algae blooms, caused by human pollution, led to the die-off.

“Manatees were literally starving to death because they couldn’t find that food,” Berchem said.

Many of the other threats manatees face are also caused by humans, UF Aquatic Animal Health Professor Michael Walsh said. Boats going too fast in shallow water can strike manatees, he said, and man-made canal locks or floodgates can also harm the species. Watercrafts account for about 10-20% of manatee deaths each year, according to data from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Algae blooms not only kill seagrass but can also pose additional threats to manatees. Red tide, a type of harmful algae bloom, is poisonous to manatees. In 2023, red tide killed more than 100 manatees.

“The challenges that are facing this species are just amazing,” he said. “And the problems are what we’re contributing.”

Manatees also face habitat loss as humans continue to encroach on natural springs and rivers, Walsh said. Florida’s spring systems have warm water temperatures year-round, which manatees need to survive.

Manatees can be found in the waters of over half of Florida’s counties but are commonly found in the Indian River Lagoon. Over the last several years, the Indian River Lagoon suffered poor water quality, and the subsequent algae blooms reduced seagrass in the area by over 90%.

A key part of protecting manatees is preserving the species’ habitat, said Alex Freeze, the collaborative conservation manager with the Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation. The Florida Wildlife Corridor focuses on land conservation and setting aside wild habitats to be permanently protected.

Part of the foundation’s focus is preserving the land around natural water bodies. Florida’s environment is interconnected, Freeze said, which means unchecked damage can have widespread impact.

“You cannot separate what happens on land from what happens in the springs from what happens in the ocean,” she said.

Part of the challenge, Freeze said, is making sure Floridians understand the impacts their individual actions could have on the environment. Some residents might not be aware of what causes harm to manatees, she added.

Educating residents on boat safety and how to avoid polluting waterways is part of what the Florida Wildlife Corridor advocates for, Freeze said.

“People as a whole want to do what’s right by the environment,” she said. “Do they have access to the knowledge, and are they supported in their pursuit of wanting to build sustainably?”

At the Florida Manatee Festival, Dianne Azzarelli said she enjoyed seeing positive education combined with fun and creativity. Azzarelli, 56, attended the festival for the first time Jan. 13. She bought a manatee T-shirt for her granddaughter and liked visiting the educational booths.

Azzarelli was happy to see the public awareness brought by the Save the Manatee Club. As a native Floridian, she said non-natives moving to the state often aren’t properly educated on how to protect manatees.

“I love that they’re imparting so much knowledge for the manatees,” she said.

Throughout the festival, first-time Save the Manatee Club volunteer April Sarna fielded questions and took donations from attendees. Sarna, 66, first saw a manatee at an aquarium in her home state of California. She said she was mesmerized by the way the aquarium manatee ate its cabbage and grew an instant appreciation for the species.

After moving to Florida, the Ocala resident joined the Save the Manatee Club and adopted a manatee named Ariel. This year, Sarna said she wanted to volunteer to learn more about manatees and show support for the species.

“It’s fun actually talking to people, and it seems like everybody’s on the same page and wanting to make a difference,” Sarna said.

Contact Kylie Williams at kyliewilliams@alligator.org. Follow her on X @KylieWilliams99.

Kylie Williams is the Spring 2025 Digital Managing Editor and a third-year journalism major. She has also worked as the enterprise editor and the environmental enterprise reporter. In her free time, she can be found reading, baking or watching reality TV with her cat.