Even after her husband cut their furniture in half with an ax, threatened to kill her and hide her body, a domestic violence survivor didn’t believe she was in an abusive relationship.

It was not until she told her story to a counselor from the Gainesville domestic violence center Peaceful Paths that the survivor, who wishes to remain anonymous for her safety, understood the gravity of her situation.

“I didn’t realize how bad it was until I told people,” she said. “I had hospitalizations because of depression, overdoses on medications. I look back now and I think I was just a robot.”

She said she understands now that even if she didn't have a broken arm or black eye, she was psychologically and emotionally abused by her husband. She’s grateful to the providers at Peaceful Paths who helped free her from her marriage.

However, federal and local funding issues for domestic violence resources have put centers like Peaceful Paths at risk. At the federal level, Congress slashed $700 million from The Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) fund's annual budget for the 2024 fiscal year. The federal assistance grant program created in 1984 supports state and local programs that assist crime victims.

The Florida Department of Children and Families shared in its 2022 annual report that federal funding resources, like the VOCA fund, make up about 66% of the funding for domestic violence resources, with over $31 million in grants and programs. There are 41 certified domestic violence centers in Florida.

Additionally, local funding challenges have forced North Central Florida shelters, like the Ocala Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Center, to close their doors. Alachua County resources are being stretched thin due to the influx of people seeking help from neighboring counties.

After more than a year of attending weekly Peaceful Paths support group sessions, the survivor said she was finally able to find her independence. She makes sure to participate in every event and donate as much as she can to the center.

“You know, the little things that I can do to support them because I don’t ever want another woman told there’s no beds,” she said.

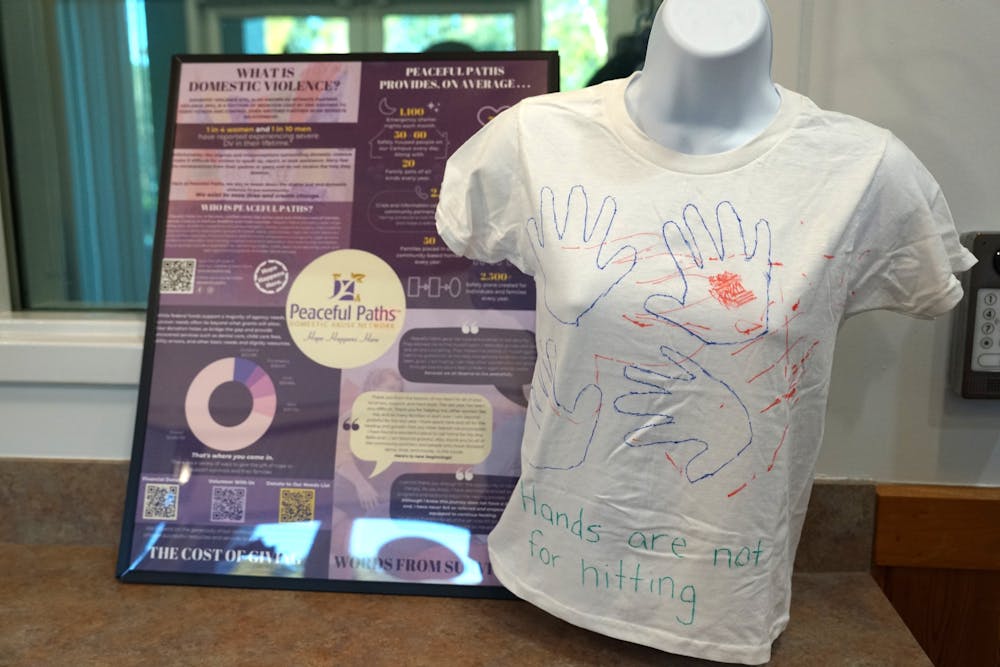

Peaceful Paths has provided over 57,000 services, such as temporary safe housing and over-the-phone assistance, to more than 3,000 survivors over the past year, according to a press release.

As Peaceful Paths receives most of its funding from VOCA, the recent budget cuts could have drastic impacts on the center, Peaceful Paths Executive Director Theresa Beachy said. The center suffered a $500,000 cut to its yearly budget this month and will take another $400,000 cut next year, unless the Florida legislature steps in to address the funding gap.

On top of funding issues, the influx of people seeking local help from surrounding areas has sparked concern from providers about depleting resources.

“VOCA cuts are not increasing numbers [of survivors seeking help] — it's reducing the amount of service we are able to provide,” Beachy said.

Beachy estimated the shelter has seen a 20% influx in people seeking services over the past 18 months. Around 20 people within the influx traveled from Marion County due to the sole Ocala shelter’s closing.

The Ocala center closure

The Ocala Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Center closed down because it lost its largest local funder, United Way of Marion County, said Judy Wilson, who was the director of the shelter.

The center was a program under Wilson’s nonprofit, Creative Services, Inc., which was created to fill in the gaps in resources for the community, she said.

The president of United Way visited the shelter and claimed it was in poor condition, and the Marion County Sheriff’s Office launched an investigation. United Way eventually withdrew its funding, shutting the shelter down.

Despite the center closure, Wilson said she wants her nonprofit to continue providing services and support for survivors and families throughout North Florida.

“We’ve talked about developing a resource center for families in trouble,” Wilson said. “To help the residents with all the resources that they need to go on with their life.”

Early education and rising cases

Lisa Wolcott, a clinical social worker and therapist, said there is a need for education on domestic violence in earlier grades because many older victims don’t understand the abusive nature of their relationships.

In high school, Wolcott said she was in an abusive relationship. But she didn’t understand the severity of her experience until she learned about intimate partner violence in college.

“I had no idea there was a name for it,” Wolcott said. “I didn’t know that it fit a kind of pattern. I didn't have anyone to talk to about it.”

A forgotten part of domestic violence is psychological abuse and harassment, Wolcott said.

“I think stalking is a big part of domestic violence that isn’t talked about,” she said.

Stalking is most common in ages 18-24 and victims struggle with anxiety, depression and insomnia, Wolcott said.

The UF Police Department reported 56 cases of stalking between 2021 and 2022, while in 2023 there are 42 reported stalking cases as of Oct. 24, according to police records.

Higher enrollment numbers may explain the crime increase, but 2023 enrollment data is pending. A 30-60% increase in enrollment would be needed to explain the rise in stalking, and UF enrollment has grown less than 6% year-to-year in the past decade.

The Gainesville Police Department reported 47 cases in 2021, 65 in 2022 and 46 in 2023, as of Oct. 24, according to police data records. The total cases of domestic violence-related cases in Alachua County increased about 15% from 2018 to 2020, according to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

Alison Glover, the lead victim advocate for the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office, said she has witnessed a rise in domestic violence cases in her unit over the past year.

In cases related to domestic violence, Glover said her agency is especially careful. Even when a call is only about a domestic disturbance, the unit ensures victims know about resources in case they need to get out of their situation.

“If there’s a history of any domestic violence in the home… [We] make sure they’re aware of the services available to them and then make sure they’re safe," she said.

The victim advocates unit is composed of four advocates working to get resources for victims. It is partly funded by VOCA grants, so their funding has gone down, too.

“With a rise in the number of cases or incidents of domestic violence and a reduction in the funding, that’s clearly going to be an issue that we’re gonna have to figure out how to support,” Glover said.

Florida’s history of financial cuts

This is not the first time U.S. domestic violence programs have dealt with severe funding challenges.

In the 1970s, the federal government established the Displaced Homemaker Program to help newly single women get back on their feet. Florida had 16 programs.

Ongoing funding issues reduced the number of programs to eight, and when the Florida legislature completely cut state funding in 2016, six programs were forced to shut down. Today, the only DHP that remains in the state is the one in Santa Fe College.

JoAnn Wilkes, a 74-year-old Gainesville resident, said after her husband died she felt she had no direction. The local DHP helped put her on a path forward.

She currently works as the coordinator for the program and helps women coming out of shelters like Peaceful Paths find jobs, finish their education and live independently.

Wilkes was in an abusive relationship in college but wasn’t able to recognize she was experiencing intimate partner violence until the relationship ended. There is too much stigma surrounding victims of domestic violence, she said.

“Sometimes it’s the community perception of people who are in abusive situations,” Wilkes said. “I think for some they think ‘Well, why didn’t she just leave?’ and it is so not easy.”

Isabella Douglas contributed to this article.

Contact Valentina Sandoval at vsandoval@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @valesrc.

Valentina Sandoval is a fourth-year journalism major and the Summer 2024 Engagement Managing Editor. Whenever she's not writing, she's expanding her Animal Crossing island, making Spotify playlists or convincing someone to follow her dog on Instagram.