Marty Jourard, a musician raised in Gainesville, lived in the city during some definitive times. Between the Civil Rights Movement, Brown v. The Board of Education and the Vietnam War, Gainesville was not necessarily a peaceful place in the 1960s and 1970s.

It was a place of civil unrest — protests, beatings and riots, but not entirely because of the hippies.

The hippie movement was a counterculture movement started by youths on college campuses in the 1960s. It was a culture that counteracted the “extreme conservatism” of the times, Marty said.

“The hippies were right. Peace and love. Make love, not war. It's not about money. Be nice to people. Be nice to Mother Nature,” Marty said. “The hippies had the right approach.”

But hippies weren’t respected outside of the hippie community. Gainesville was a “liberal oasis” in a conservative state, he said. However, there were areas of Gainesville that were dangerous for hippies to venture into.

“In Gainesville, you could get your ass beat by rednecks if you went to the wrong part of town,” Marty said. “They would cross the street to beat you up.”

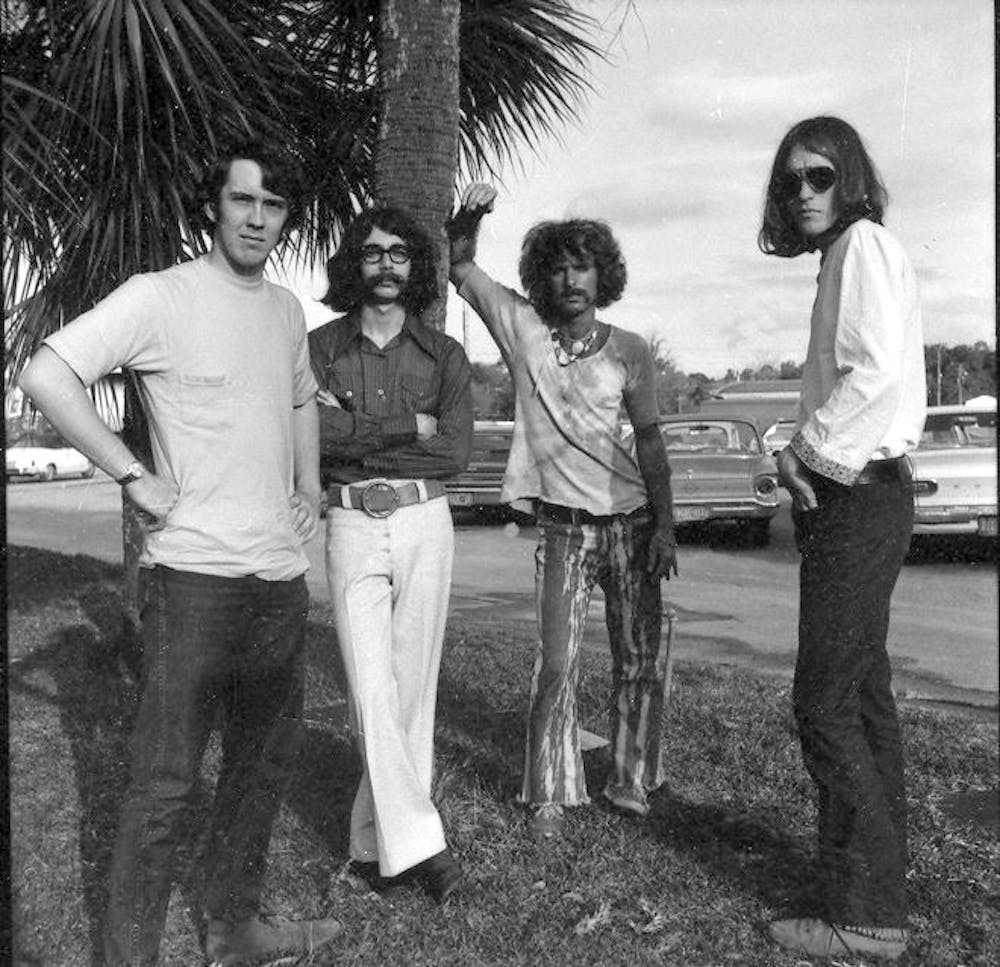

Hippies wore different clothes, used psychedelic drugs, grew their hair long and created new genres of music, but the hippie movement was much more complex than that, Marty said.

“It was a protest against the status quo of American culture,” he said.

Hippies believed in peace and love, and that belief carried into anti-war protests and the Civil Rights movement. Over everything, hippies fought for and supported equality, Marty said.

“You wanted to be peaceful. You wanted to cooperate with other people,” he said. “You were inclusive. You smoked marijuana. You took LSD.”

Marty’s brother, Jeff Jourard, 72, was a few years older and had a different perspective during the hippie movement. He was in the thick of it, and the hippie movement gave people the feeling that a revolution was coming, Jeff said.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, something like a revolution hit Gainesville: residents and students protested the Vietnam war and supported the Civil Rights movement, he said.

Hippies were different from the generations before them. They rejected mainstream American life and searched for alternative lifestyles, but it wasn’t a widely accepted theme among older Americans.

“There was people coming through for the Chicago Seven,” Jeff said. “All of these political and lefty kind of organizations were looking for support, and it got a lot of pushback from the conservative world who saw that as a threat.”

The Chicago Seven was one of the Nixon-era trials that aimed to suppress anti-war sentiment. All seven men were on trial for criminal conspiracy and incitement to riot in 1969. In 1972, two years after the seven were convicted, all criminal and contempt convictions were thrown out in appellate court.

Post-war America was a clean-cut, corporate “utopia,” Jeff said. It offered Americans who had lived through the Great Depression and two world wars a life with safe suburbs, quality entertainment, neighborhood barbeques and vacations. Post-war America was traditional, but it was a dream for some.

Hippies, however, couldn’t imagine something more boring, he said. Corporate America, to hippies, was no different than a “cleaned up prison,” and young people dreamt they could be anything, he said.

The hippie movement reached its heights in the late ‘60s, with anti-war protests becoming a fundamental part of the movement, according to History.com.

UF was no different.

Anti-war protests

On Oct. 15, 1969, about 1,800 UF students gathered at the Plaza of the Americas to protest the Vietnam War. The Student Mobilization Committee sold red and black armbands with ‘644,000’ on them, representing the estimated number of U.S. casualties in the war, according to UF archives.

On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard shot 13 students, killing four and injuring nine others. The Kent State shooting triggered national retaliation, with hundreds of colleges and universities closing down because of it, according to Kent State University.

UF students requested that then-president Stephen O’Connell cancel classes in honor of the victims of the shooting, but he didn't. It’s estimated that 3,000 UF students protested, causing classes to be canceled for two days.

Two years later, in May 1972, an anti-war demonstration spilled out onto the streets at the intersection of University and Northwest 13th Street. The mandatory draft was a consistent problem, Jeff said.

“There was a lot of anger and resentment over shipping off young people to just get slaughtered to make some kind of an abstract point,” he said. “The North remained communist, the South was sympathetic with Western values, and zillions of people got killed and burned. It didn't really settle much of anything.”

Others recall this particular anti-war protest as violent, too. Scott Camil, one of the Gainesville Eight, is a coordinator for Vietnam Veterans against the War. Veterans added a level of credibility to the anti-war movement that wasn’t previously there, he said.

“They [pro-war supporters] lost those arguments,” Camil said. “They couldn't say that we didn't know what we were talking about because we didn't read about foreign policy. We were the foreign policy.”

Camil was part of the May 1972 protest, he said. The protest lasted two days, continuing through the nights. It left 18 police officers hospitalized. Fifty-four more police officers were treated at the protest and 400 students were arrested. But none of the veterans that participated was hurt or arrested, Camil said.

However, once the veterans’ city-assigned protest permit ran out of time, they removed the barricades that created the blockade and left the streets, but the students didn’t leave. The students also didn’t move when 1972 student body president, Samuel Taylor, urged them off the streets.

Students didn’t move when fire trucks were brought in to spray them off the street — in fact, this only made the crowd larger because it provided sweet relief to hot May weather, Camil said. Students weren’t strongly affected by the tear gas police officers threw because the officers were standing downwind, and it backfired.

The veterans interfered with the protest when police officers, four to six deep, sidewalk to sidewalk, started to get violent with the protesters, especially the young, female protesters, Camil said.

“We used slingshots and projectiles and we just blasted their asses,” Camil said. “They were used to beating the sh-t out of the students. They weren't used to standing up against combat veterans, and we let them see that we weren't going to allow this kind of activity against the students.”

Camil, along with seven other men, would go down in history as the Gainesville Eight.

The Gainesville Eight

The Gainesville Eight, similar to the Chicago Seven, Harrisburg Seven and Camden 28, were part of one of the many Nixon-era conspiracy trials that occurred in the 1960s and ’70s. Trials like these were infamous for trying to suppress anti-war support.

Aug. 31, 2023, marks the 50th anniversary of the Gainesville Eight being acquitted on all charges. Seven of the eight men were Vietnam veterans, and today, only five of the eight are still alive.

Gainesville Mayor Harvey Ward welcomed the five men back to Gainesville Aug. 31 and read a proclamation praising the group for its historical significance and work for peace, according to The Gainesville Sun.

In 1973, the jury deliberated for three and a half hours before deciding the defendants were not guilty, according to New York Times archives. The U.S. government tried a case no one expected them to win, Camil said.

“I'm proud of what we did. I'm proud of what we stood for,” Camil said. “We were exercising those constitutional rights that we not only inherited, but we also bled for.”

An outside perspective

Bill Killeen wasn’t too far off from being considered a hippie in the ’60s and ’70s, but he didn’t consider himself one, and most hippies in the area didn’t consider him one either, he said. Killeen opened his store, which primarily served hippies, when he was 27.

He opened The Subterranean Circus in 1967 on Seventh Street with $1,200, and despite calling himself a “fool” for opening a store with a small amount of money, the store kept growing, he said. He sold hippie clothes and drug paraphernalia and frequented New York to buy both.

Killeen saw his fair share of protests, ranging from Civil Rights protests to anti-war protests. He recalls watching the 1972 protest die during the day before picking back up again at night, he said.

“It just went on and on,” he said. “It was rough.”

The hippie movement opened the door to a distrust in the U.S. government, Killeen said.

“The draft is something that's going to cause you problems,” he said. “But also people stopped trusting the politicians.”

The hippie movement came to an end in the mid-1970s, around the same time the Vietnam War ended, but hippie ideology lives on through some.

“People started smoking pot, people started taking acid — the music, the art, — everything came along at the same time,” Killeen said. “It was very, very unique, and every aspect of it was just stunning.”

Contact Ella Thompson at ethompson@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @elladeethompson.

Ella Thompson is the Spring 2025 Editor-in-Chief and a fourth-year journalism major. She also worked as the Fall 2024 Digital Managing Editor and the Spring 2024 metro editor. In her free time, she can be found reading, planning a trip or journaling.