In the classroom of an environmental science teacher one will see many things. Lab coats. Goggles. Maps. Skeletons of animals tangled in nets.

John Pettit sees the future.

“I feel like I am going to be influencing our next generation of leaders,” he said.

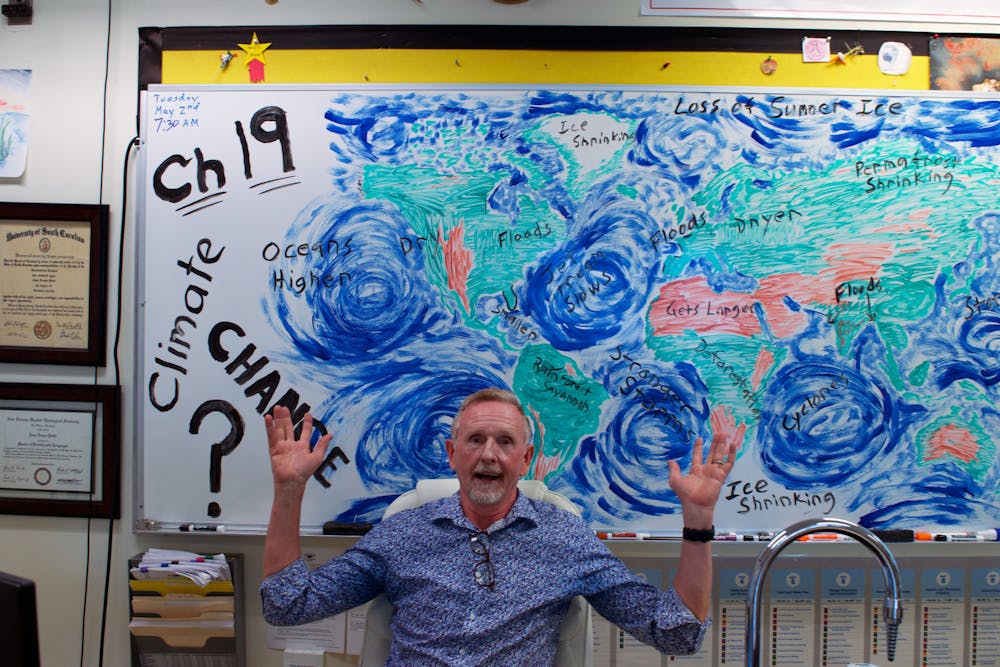

Pettit, 58, has taught environmental science at Buchholz High School for nearly six years, and around a third of his curriculum focuses on climate change.

The list of Florida state standards for science classes under environmental science include 39 items, 14 of which are specifically related to climate change, according to CPalms, a database of standards and resources created by Florida State University. Teachers are required to tailor lessons to topics like the costs of fossil fuels and greenhouse gases.

Environmental science is solely focused on the relationship between humans and the environment, but other core classes like Earth science do include standards related to climate change, such as causes and the impact the ocean plays in global warming.

While not everyone in class is always rapt with attention, including climate change in Pettit’s lessons hasn’t been met with significant pushback from students or parents over the years.

He doesn’t see himself as a “doom and gloom” guy. He tries to address hard science first, but at the end of the day, he said, he also tries to encourage his students to see the possible ways for them to effect change.

“I point out with my kids a lot of times: ‘Unfortunately, your generation is going to have to fix what my generation did, but that's OK,’” Pettit said.

Before he was a teacher, he did economic development work all across Asia. He traveled to the snowy mountains of Nepal, the rainforests of Thailand and the savannas of India working to improve poverty and the well-being of large populations. He has seen the negative effects of human activity on the environment in a variety of places.

He often references these experiences in class to tie what his students learn to reality.

“When I talk about poverty and population, it's not a theoretical with me,” Pettit said. “Pictures that I'll put up on the screen of where we've been and what we've done, it's more tangible.”

Besides teaching about how climate change impacts rising seas and the loss of biodiversity due to human activity, Pettit said there are four main elements to environmental science: poverty, population, pollution and petrochemicals.

When he was still in the field, he worked on addressing poverty and the strain an increasing population has on the natural environment. Now, as a teacher, he focuses on teaching students about pollution and petrochemicals, like how oil and waste spills have large-scale environmental impacts.

One of Pettit’s student’s, 17-year-old Angela Gao, has taken her environmental education a step further.

Since the sixth grade, Gao has worked on independent research in the field of environmental engineering. She works mostly with biochar, a charcoal-like carbon formed when organic materials like wood or grass are heated up to extremely high temperatures with low-oxygen.

Gao hopes to refine a way to use biochar to reduce and prevent pollution, she said.

Biochar is porous, so it’s used to soak up pollutants in soil, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Growing up in Florida, it gives you a firsthand sort of look into some of the effects of climate change and global warming,” she said. “We have so many aquatic ecosystems, so that's how I really got my start in this.”

Her class with Pettit was the place where she realized the research she was doing had the potential to make an impact and help the environment, she said.

However, she said, she feels like the current curriculum needs to expand on this aspect more.

“We could get more people sort of aware of the interactions between humans and the environment and just how critical it is at this point in time,” Gao said. “We need to be addressing these sorts of issues.”

She has several suggestions for ways Alachua County Public Schools can spread more awareness on the topic, she said, including making environmental science a required class or hosting annual sustainability assemblies. Gao wants to see more of her fellow students working together to help the planet, she said.

Another Buchholz student, Morgan Smith, 18, was also greatly impacted by her environmental science class. She was always aware of environmental issues, but taking the class her freshman year really opened her eyes, she said.

“Change needs to happen,” Smith said.

Edward Hunter is an environmental science teacher from Gainesville High School. He agrees that more students need to take a stand.

“They need to know not just what's going on … that the climate is changing, the planet is warming, that these consequences are starting to happen,” Hunter said., “Bbut we need to have them on board in terms of making changes in their own lives.”

Like Pettit, Hunter has never received backlash for his curriculum from students or parents. He also has never been told that there isn’t anything he can’t teach, he said.

In his class, he covers general environmental science topics like water pollution, renewable and non-renewable resources, global warming and other consequences of climate change.

As a teacher, he sees his role as simply an informant, he said. He’s there to spread awareness of issues in the community and the world — but, most of all, he wants to empower his students.

“The situation is tiptoeing up to a really critical pivot point,” Hunter said. “People need to understand that everything we do is important.”

Pettit also shares this belief.

While ACPS teachers rarely receive pushback on climate change teachings, Pettit has seen a change in the overall attitude of society. What people once believed to be a hoax is now seen as hopeless, he said.

“We've shifted from ‘It's a hoax’ to 'There's nothing you can do about it, so, don't worry about it,’” Pettit said. “My main push to my kids [is] we all have to do something.”

That is why he shifted from the field to a classroom. He believes his students have the power to make the world a better place. He would retire or go back out to the savannas and rainforests if it didn’t feel like he was helping, Pettit said.

“If it didn't,” he said, “I would leave tomorrow.”

But he knows it does.

There is a water project he assigns to his students, in which they track how many liters of water they use in a day. Afterward, they’re challenged to see how much water they can save, with his experiences in Nepal as an example.

When he was doing field work in Nepal, he used just under 20 liters of water a day. That is the average amount of water a local Nepali uses, he said.

Typical American teenagers use about 300 liters of water a day, and most people can easily save between 20 to 30 liters, Pettit said. In the U.S., it’s difficult to reduce water use to just 20 liters. And even if one person saves 30 liters, it doesn’t seem like that much.

However, if all of Pettit’s 200 students save 20 liters each, that’s over 2,000 liters of water per day, he said.

He knows the future of his students matters, and that can only be achieved through their joint effort, he said.

“That's the power of environmental science,” Pettit said. “It's not a few of us doing a lot — it's a lot of us doing a little that's going to make the big difference.”

Contact Aubrey at abocalan@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @aubreyyrosee.

Aubrey Bocalan is a third-year journalism major. She is also pursuing a double major in Art. When she isn't writing, she's probably watching TV with her dog, Albus Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore Bocalan.