A bell rings every time someone opens the door. That ringing echoes through the long yellow building called the Cotton Club Museum and Cultural Center.

In its past, it was a theater, then a big-bands club and most recently, a furniture warehouse. It dates back to the 1930s when a group of World War II soldiers built the place.

Once inside, walls full of Black art and the following eyes of murals greet attendees. At one end of the building is a stage that has seen the likes of music artists James Brown, B.B. King and Bo Diddley.

On Jan. 14, a four-chair panel was set in front of that stage in preparation for “Beyond the Headlines: Exploring the Gainesville Sun’s Covering of Race Relations.” The four panelists found it fitting that the presentation was only days before Martin Luther King Day. The event took the audience through the late 1800s and early 1900s of Black news not covered by the Sun and how southern newspapers are trying to make up for their mistakes.

Vivian Filer, the Museum’s CEO, founder, chair of the board and one of the panelists, reminded the nearly 60 people in attendance that MLK Day isn’t one for rest, but for action.

“We who believe in freedom cannot rest,” said Filer, 84, to those in the crowd.

This presentation is part one of a possible three-part series conducted by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, UF’s official oral history program. All parts are included in the Challenging Racism initiative SPOHP has started.

Paul Ortiz, Adolfho Romero and Donovan Carter filled the three other seats on the panel. They all recounted the history of the Gainesville Sun and other southern newspapers that failed to report on crime, injustice and news about Black citizens.

Romero, the co-assistant director of SPOHP, said the presentation shows the most striking examples of the Gainesville Sun failing to tell stories about the black community. Choosing those examples was challenging, given how many accounts they read through.

“There is so much material,” Romero said about what he refers to as “silences.”

A ‘silence’ is when a newspaper chooses not to report a story. He read stories about lynching, KKK murders and the shooting of a 10-year-old Black boy, none of which ever made the paper.

The crowd in the museum was made of all ages.

The Cotton Club will teach everyone “from the cradle to the grave,” Filer said.

Timothy Sinclair, 20, said he was in the crowd to take advantage of the lessons taught. He said it was a goal of his fraternity at UF, Omega Psi Phi, to go out and learn more about Black culture.

Sinclair and a handful of others in the crowd took advantage of the question-and-answer portion of the panel. A part of the night that highlighted topics like Black-on-Black violence, the portrayal of Black men in media and the need for a reliable daily newspaper.

To Filer, there’s a need to teach these topics through local media.

“I am not here to make it look pretty; it was painful,” Filer said.

No one believes in this mission of education as much as Filer.

She has grown with the city of Gainesville since she was 7 years old. At that time, she attended the only Black high school in Gainesville, Lincoln High School, then studied at Sante Fe College and UF once schools were desegregated.

What the Cotton Club teaches cannot be found in school history books — lessons about slavery and the hardships experienced by Black people in the last 550 years, she said.

While the spoken stories told in the museum are about the hardships of enslaved Black and emancipated people, the exhibits show their resilience, culture and resourcefulness.

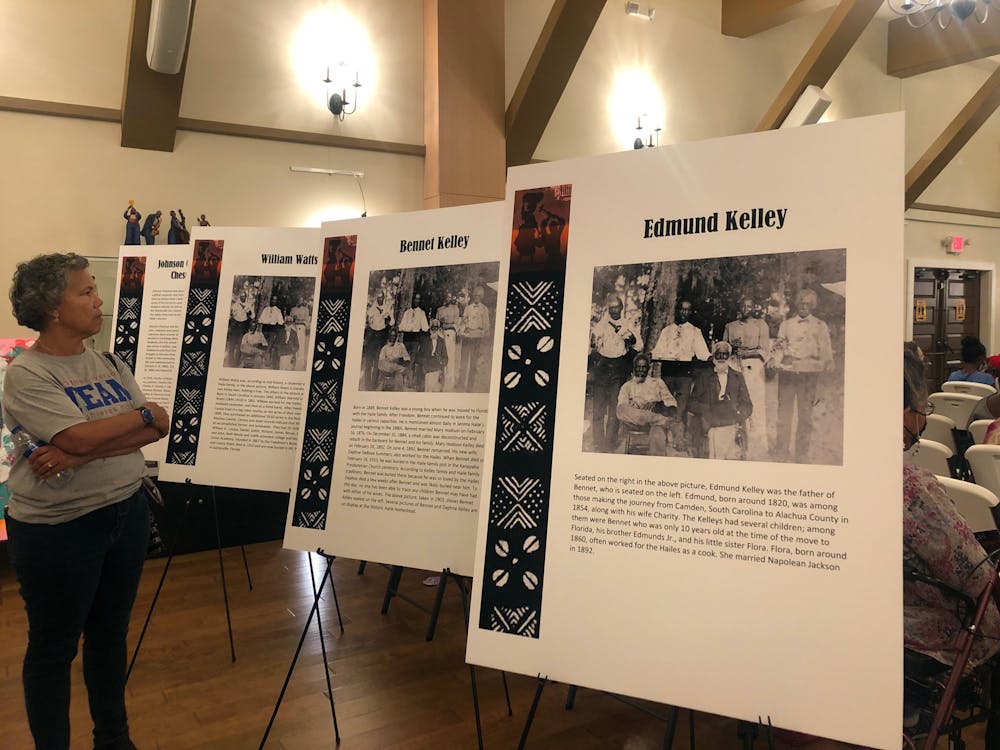

Exhibits are up at the Museum with lessons about the Gullah Geeche people and stories from the more than 18 former plantations in Alachua County, both of which are not a part of the school curriculum in Florida.

The Gullah Geeche are the descendants of formerly enslaved people living on the Atlantic Coastline from Georgia to Virginia, heralded for their fishing techniques.

From events that highlight the importance of covering race in media to exhibits that enrich the youth’s understanding of Black history, Filer and the Cotton Club strive to make an impact.

The Sankofa bird is a perfect model for the museum’s mission, Filer said. The symbol of knowledge is found repeatedly in African studies.

“Feet planted forward, head looking back,” Filer said.

Contact Jake at jlynch@alligator.org. Follow him on Twitter @JakeLyn20488762.

Jake Lynch is a third-year journalism major. He is a South Florida native that loves to spend time with family and friends. He has no idea what he wants to do with his life but he hopes this helps.