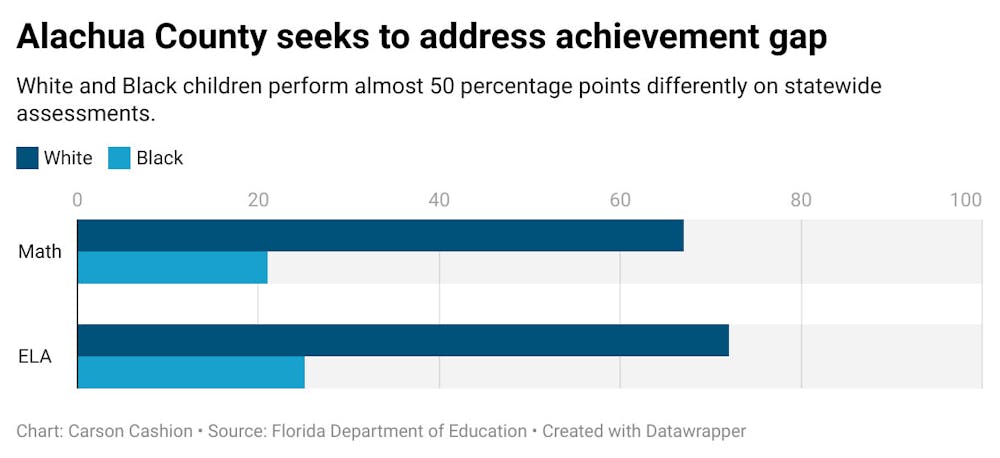

ACPS has the state’s widest achievement gap between white and Black students in both English language arts and mathematics. Segregation met its end in 1970 for Alachua County Public Schools, but disparities between Black student and white student performance afflict the district today.

This district serves more than 30,000 students — 33% of which are Black and 41% of which are white. ACPS officials acknowledged this gap and crafted an equity plan in 2018, promising to eliminate the disparity by 2028, but the plan failed to narrow the difference in student performance.

It outlined goals like raising the performance of Black students in reading and math by three percentage points each year, but the gap widened as the district failed to implement any policy changes to meet its goal, ACPS school board member Tina Certain said.

The gap continues to divide Black and white students in pursuit of educational success.

The district can’t task its teachers with overcoming the achievement gap. Every district in the state has a gap, and factors outside the classroom are at play.

The Alachua County Education Association’s service unit director Crystal Tessmann said years of systemic poverty and racism entrenched in society have aided the gap’s formation.

The achievement gap is the difference between the percentage of white students who received a passing score, a level three, on the Florida Standards Assessment and the percentage of Black students who received a passing score.

The reality of separate, but not equal during segregation has manifested itself in this achievement gap, Tessmann said.

“It just got a different name and kept disenfranchising and hurting the kids who needed the most,” she said.

She taught at Metcalfe Elementary for nine years.

Metcalfe is home to an 84% Black student population, according to school-level demographics. Last year, 18% of its fourth graders passed the English Language Arts FSA, below the district’s 51%.

She loved her time teaching there and made score gains with her students, but when the state came in after the school received an F for its grade as a result of low FSA scores, state coaches made teachers feel as if they could never do enough.

“Sometimes it comes off that it’s the teacher’s fault that the achievement gap is happening, and instead it needs to be how can we empower teachers to fight the achievement gap?” Tessmann said.

Of Florida’s 75 districts, Alachua’s gap remains the largest with a 47 percentage point difference in ELA and a 46 percentage point difference in math. Miami-Dade follows with a 39 percentage point gap in ELA and a 40 percentage point gap in math.

The district is trying to tackle this divide.

Although the district has not created another equity plan, new programs began this August that aim to improve student achievement, Certain said. These contrast the lack of policies initiated with the 2018 equity plan.

One of these new programs resulted from a partnership with University of Florida’s College of Education: the University of Florida Literacy Institute, referred to as UFLI. This program trained teachers last summer and was implemented in every kindergarten through second grade classroom districtwide. It is a research-based phonics curriculum that teaches students to read with multi-sensory activities such as hand motions and chanting.

Instead of mediating students once they reach the testing grades as third graders, Certain said the district can build up students’ literacy skills to prevent the need for remediation.

However, she expects the achievement gap to stay the same or even widen because of pandemic-related learning losses, which hit students of color particularly hard. Students of color were not in classrooms when COVID was at its height, Certain said. Many elected to learn remotely or were quarantined often because of exposure, so learning loss is expected.

Even if the gap remains the same or widens after this year’s testing, the UFLI program remains promising. Through district progress monitoring, kindergarten through second grade students show improvement, ACPS spokesperson Jackie Johnson said. These students were behind their peer groups from previous years at first but have progressed beyond where their peer groups were at this time last year.

“We attribute a lot of that to the success of the UFLI program,” Johnson said. “And, of course, teaching kids to read and making sure that by third grade they have learned to read and are able to begin reading to learn — that is huge.”

Reading skills receive an emphasis because success in both reading and math on statewide assessments is dependent upon a student’s ability to read and comprehend the question presented.

The district implements other tutoring programs called Beyond the Bell and High Dose. Beyond the Bell is an afterschool program available to all students and taught by the district’s teachers, offering homework help across all subjects. High Dose tutoring pulls students who are struggling primarily with reading in all grade levels for one-on-one or small group tutoring with a paraprofessional.

Students who reinforce such skills at a younger age could help close the achievement gap, which disproportionately affects predominantly Black schools on the east side of Gainesville.

For example, on the east side, Black students make up 80% of Lake Forest Elementary School’s population. Last year, 15% of Lake Forest’s third graders passed the ELA FSA, which is below the district’s passing rate of 53%, and 21% passed math, below the district’s 51%.

On the west side, Black students make up 21% of Hidden Oak Elementary School’s population. For Hidden Oak’s third grade students, 75% passed ELA and 68% passed math, exceeding the district’s passing rate. Hidden Oak’s ELA pass rate gap between Black and white students sits higher than the district’s gap at 55 percentage points.

The school may perform above the district, yet its Black students are left behind.

Funding per student is the same for each school in the district. Although the 2019-2020 cost per student by school shows Lake Forest received $3,176 more than Hidden Oak. But Lake Forest has 346 students where Hidden Oak has 786 students, so when the same funding is divided per student, it appears unequal.

Schools like Lake Forest receive extra state funding because of their Title I and turnaround school status. Schools receive Title I status when they are determined to have several economically disadvantaged students, and ACPS is home to 33 Title I schools. Turnaround status is given to schools who earn consecutive school grades below a C.

Extra funding does not translate to improved test scores. Factors like lack of background knowledge, less experienced teachers, differing behavior plans and unstable home lives contribute to ACPS’ achievement gap.

“Affluent students come to school having had better preschool and early learning experiences,” Certain said. “They come from households where they’re surrounded or exposed to more things that are educational and that build up their knowledge base.”

High-stakes testing like FSA is composed of questions written from a white person’s perspective, Certain said. Word choice and word use might not be familiar to children who do not share the same background as their white counterparts.

The district also aims to provide students, especially disadvantaged students, with experiences they might not have. It partnered with the Cade Museum to form a program called Full Steam Ahead that arranges field trips for students to receive hands-on science activities, Johnson said. This program has not seen its full potential due to the pandemic.

Differences in background and experience make in-classroom learning vital for students. But teachers in predominantly Black schools tend to be less experienced.

“Mediocrity for a poor child or a child that’s at a low-performing school has a far more reaching, negative impact on that child’s life,” Certain said.

But closing the gap goes beyond curriculum and literacy programs.

Black students experience a higher rate of out-of-school suspensions than all other students. In the 2019-2020 school year, three times as many Black students received an out-of-school suspension than white students. Such discipline removes them from instructional time and hinders learning.

Former superintendent Carlee Simon said student behavior is managed at the school building level, so strategies and approaches differ depending on the leadership at each school. Before the board voted to fire Simon in March, she worked on implementing a district-wide behavior plan to establish an expectation of consistency.

State testing data reveals the achievement gap between Black and white students, but it reaches further than a pass or fail on an assessment. Multiple factors shape a student’s educational environment and learning opportunities. Exactly why this type of gap exists in Alachua and in every other school district in the state fails to be pinpointed.

A swath of programs and pandemic-relief funding promises to raise Black student performance across the district, but the effects of such initiatives require time, patience and another cycle of testing data.

Contact Emma at ebehrmann@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @emmabehrmann.

Emma Behrmann is a fourth-year journalism major and the Fall 2023 digital managing editor. In the past, she was metro desk editor, K-12 education reporter and a university news assistant. When she's not reporting, she's lifting at the gym.