Rik Stevenson likes to challenge his students with questions each class: “Who is Claudette Colvin? How many slave ships remain untouched at the bottom of the ocean? Who is Bessie Coleman?”

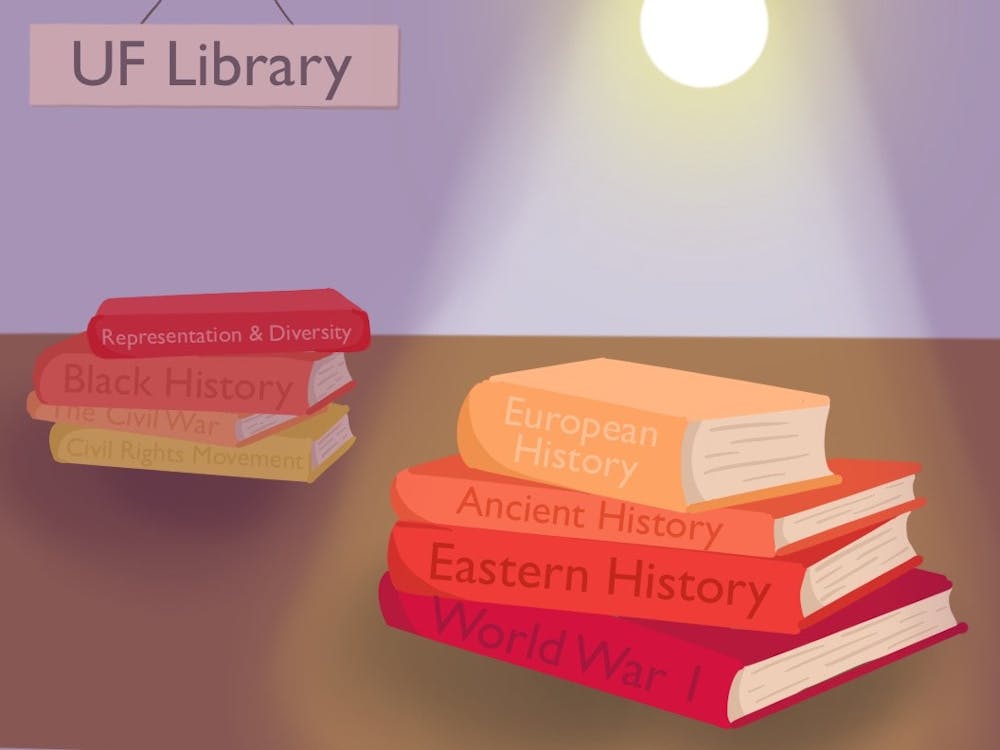

Few students know the answers to these questions, signaling to the African American Studies professor that a bigger problem exists: UF students lack a proper education in African American history.

“I just think that the under-education of our student population is doing us much more harm than it does good,” Stevenson said.

Stevenson uses a teaching methodology called critical pedagogy, or teaching through inquiry. He frequently asks students questions about historical people and analyses only to find they have never heard of them.

The main problem is that Black history is not traditionally taught as a part of American history, he said.

This appears to be a problem that extends into the Alachua County public schools. Parents have voiced concerns about the lack of Black history integration despite the county having a state-recognized African American studies curriculum.

At the individual level, he said taking the time you would spend on social media and redirecting that attention to research would help close the gap of knowledge disparity.

To combat this lack of education from the university level, Stevenson believes student advising should better market the courses that the African American Studies department offers.

“A student who sees African American history as integrated into the American history context has a better perspective of what it means to really be American,” he said.

It is important to go back and learn and acknowledge our past, said Yasmine Adams, a 22-year-old English major with minors in African American Studies and anthropology. History in general is important to understand the context of the present, she said.

Most of Adams’ professors in the African American Studies program are Black, she said, which provides an Afrocentric lense that regular history courses may not have.

“[The classes] are often taught from people who have experience in things that we are talking about,” she said. “I find that a lot of times my professors are very engaged and it’s very obvious that what they’re talking about is so important to them.”

Roughly 73% of the professors in the African American Studies department are Black while only about 8% are White, according to UF’s workforce database.

There is also no fear that the course will be whitewashed because African American history is what it is, and the instructors teaching it are genuinely interested in uncovering the truth, Adams said.

Adams feels African American history is not emphasized enough in UF’s education. Students either do not see it as important or the university does not take the time to notify students about the courses they are offering, she said.

“My Black friends, our pursuit of Black history is because of our experiences and so we feel the need to be involved and be knowledgeable,” she said. “But when it comes to the academy, I don’t see that same interest being put out there.”

Approximately 79% of students majoring in African American Studies are Black and 6.5% are White, according to UF’s student enrollment and demographics database.

The university does not require courses that teach African American studies and Black history, but its Quest program can expose students to equitable courses as a part of their general education, said Angela Lindner, associate provost for undergraduate affairs.

UF’s Quest courses examine difficult questions about the human condition in our changing world, according to the description on the program’s webpage.

Quest replaced the “What is the Good Life” course in Spring 2019. It was clear that one course was not sufficient to create truly well-rounded students, Lindner said.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the program requested that professors propose courses about racism and antiracism.

These requests, she said, prompted courses like “Acting for Change,” “Black Women’s Work in Film,” “Dance, Race, Gender” and “Journalism, Justice and Civic Change,” which were offered this Spring.

Courses like these are a start, Stevenson wrote in a text message.

“I think initially there should be more course[s] that highlight African[s] before the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” he wrote.

UF added a second required course for Quest program this year. The goal is to add a major experiential learning third course by 2027, she said.

Lindner approves courses as the chair of the university curriculum committee and the general education committee. But the committees have no say in course content. Instead they examine the courses’ objectives, the weekly course schedule, how students are being graded and if they are being graded fairly, she said.

Course content is determined at the college and department level, she said.

“The gen-ed committee doesn’t push for specific courses; that’s not the role of the committee,” she said. “We’re not going to tell them they can’t teach certain content; that’s just not our job. We are here to help.”

UF’s curriculum changes always start with the faculty, she said, then the committees review their requests to ensure they meet the standard guidelines.

Both committees are made up of UF Faculty Senate members, members appointed by the provost and representation from UF’s student government, which allows students to have a voice in their curriculum, Lindner said.

Lindner encourages any faculty members who have questions or suggestions to come to them, and the committees will support them through the process.

“We all have to have skin in this game,” Lindner said. “The community cannot rely just on the administration to make change. We’re on this every day, but it’s got to come from students, it’s got to come from faculty.”

While changing and adding to the curriculum seems like the obvious solution, Vincent Adejumo, a UF senior lecturer of African American Studies, said he does not believe requiring students to take courses in African American history is the solution.

Requiring studies in one culture, Adejumo said, then poses the question of whether studies in other cultures like Latin American groups and Jewish groups should be required too.

“If a person isn’t interested in learning it, especially as a college-age student, then they shouldn’t be mandated,” he said. “I think what the university can do is be open to more programming that is more African American centered.”

On Feb. 8, UF Student Government funded a Black History Month concert headlined by Roddy Ricch, who was paid $350,000 to perform.

SG funded another Black History Month concert two years ago on Feb. 24, 2020, that was headlined by Tory Lanez. He was paid $91,500 to perform.

A better allocation of this money would be to use the funds for getting a series of speakers and scholars to come to the school not only during Black History Month, but the entire year, Adejumo said.

“At the end of the day [the students] want to have fun, and that’s fine,” he said. “But if the university is serious, they would look into bringing more serious people in to talk about these issues.”

Students have to demand these changes because without it the administration has no incentive to change, he said.

Students could pay more attention to what’s going on with the faculty even if they are not choosing to take courses in African American studies, Adejumo said. Administration could also do a better job at putting out press releases and keeping students informed on the inner workings of faculty members, he said.

Tackling this issue of educational disparity calls for an all-hands-on-deck approach.

If the urgency for change begins to ripple throughout the student body, faculty and administrators, then maybe more students would know the answers to Stevenson’s questions.

They’d be able to confidently say Bessie Coleman was the first Black woman to get a flying license, that nearly a thousand slave ships rest peacefully on the ocean floor and that Claudette Colvin, a dark-skinned and pregnant 15 year-old, was the first Black woman to refuse to give up her seat on a bus.

Contact Elena Barrera at ebarrera@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @elenabarreraaa.

Elena is a second-year journalism major with a minor in health sciences. She is currently the University Administration reporter for The Alligator. When she is not writing, Elena loves to work out, go to the beach and spend time with her friends and family.