Alachua County Public Schools’ curriculum promises Black history education to extend beyond the month of February and the few names repeated in history textbooks. However, not every classroom fulfills this promise.

The state awarded ACPS an exemplary title in 2021 for outstanding African American studies curriculum, K-12 social studies curriculum specialist Jon Rehm said.

ACPS set a goal in 2018 to build an exemplary African American studies curriculum because more than a third of its students are Black, Rehm said. The district spent most of 2019 and the beginning of 2020 creating a curriculum that includes education from Ancient Africa to slavery to abolition and centers contributions of African Americans in areas like art, literature and science.

The curriculum gives K-12 teachers pre-made guides with suggested material, Rehm said. Educators retain creative freedom and can go beyond those units while sticking to the district-wide curriculum at each grade level.

ACPS also offers African American History, an elective available at each high school in Alachua County. Students who take this course get a deeper understanding than in an ordinary history class.

African American History has not always been an accessible course. Prior to the new African American studies curriculum that earned the exemplary title, only one high school — Eastside — offered the elective.

Now, each high school has one section of the course, and each section averages about 25 students. Eastside, which tends to be the district’s largest school, typically has two sections.

“I think we’re having a much more robust conversation throughout all of our schools because of this curriculum,” Rehm said.

Although the curriculum earned the title of exemplary, the teachers still decide what’s taught in their classrooms.

Gaps in curriculum persist

Students who enroll in the African American History elective get a deeper understanding of Black history through literature, film and reflective assignments. However, students in elementary school, middle school or regular history classes still miss out.

The district can monitor how many teachers access Black history classroom materials via Google Drive. The district also conducts school administration walkthroughs to ensure students learn the material.

Despite these assessments, some parents don’t believe their children are receiving an adequate understanding of their own history.

Derora Williams, a parent of a second grader and fifth grader at Carolyn Beatrice Parker Elementary School, said her children learn the same names every February: Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman.

The district’s curriculum designates Black history in second grade to focus on the influence of Africa on North American Culture through map labeling and topics like tradition comparisons. It recommends fifth grade classrooms focus on topics like the triangular trade and famous African Americans in the American Revolution.

However, the few figures Williams’ children have learned about don’t relate to these topics. Williams said their knowledge of Black history is limited to the month of February.

Carolyn Beatrice Parker Elementary’s principal Kelly Brill Jones said Black History Month is important to her school community.

“February is designated Black History Month which provides our teachers with a time to more closely focus on the achievements, contributions and struggles of Black Americans,” Jones wrote in an email.

Carolyn Beatrice Parker Elementary is named in honor of a female Black physicist, which creates opportunities throughout the school year to weave Black history into classrooms, Jones wrote.

She conducts formal and informal observations of the teachers and said she is confident they follow the state’s benchmarks and district pacing guides. Because the school has an ESOL program, teaching and embracing the history, heritage and culture of diverse populations is an integral part of the school climate.

However, Williams, a program coordinator for the Alachua County School Board and former eighth grade language arts teacher, believes her children’s Black history education is lacking.

“I made sure that I extended [Black history] beyond just a month,” Williams said of her time as a teacher. “Because I wanted my students to know and recognize that there’s so many contributions and so many things that they should know.”

What is taught depends on the teacher, Buchholz High School’s African American History teacher Jessica Morey said.

“If I were to describe the county as a whole, I’m sure it’s a total hodgepodge,” Morey said. “Because it’s honestly what the teacher brings to the class.”’

Teachers put their spin on the curriculum

Educators are granted creative freedom with the district’s curriculum, and African American History teachers take advantage of this freedom.

Newberry Mayor Jordan Marlowe, also a Newberry High School African American History teacher, doesn’t use the guide provided in Canvas, an online learning platform, to teach his students.

“I think the county curriculum is excellent,” Marlowe said. “But in my perspective, as a teacher, teaching history is really only relevant in order to understand the present, so I’m not interested in recitation or just knowing the history. I only need you to know history so that you understand today.”

In Marlowe’s class, he offers an interactive learning experience to students. He invites guest speakers to talk about what Black history looks like in Newberry and Alachua.

“Part of me feels like there should be an African American teacher teaching African American History,” Marlowe, who is white, said. “But Alachua County has so few African American teachers that it’s difficult. But part of me also feels that African American students need to see and hear a white man say these things happened. These things were wrong. We can do better.”

As of the 2019-20 school year, 11% of ACPS teachers identify as Black and 81% identify as white. Meanwhile, 34% of the districts’ students are Black and 44% are white.

His class goes on field trips — they saw “Harriet Tubman” when it first came out. They created a festival called Soul Fest in 2019 to introduce African American History into the community and raise money for a potential field trip to Montgomery, Alabama.

“One of the injustices that we’ve done when it comes to African American History is we reduced it to Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X and just a handful of people and events,” Marlowe said. “When I look at my city and my community, we have a lot of activists that have been in the trenches doing this work here for the last 100 years.”

The county seeks to improve the curriculum, Rehm said, by adding Florida and Alachua County history. Marlowe said he has taken this step.

His class just concluded its unit on the 1916 Newberry lynchings — known as the Newberry Six. White mobs lynched six Black men and women after a Black farmer was accused of mortally wounding a Newberry office holder. Although referred to as the Newberry Six, oral history suggests a total of nine Black men and women were killed.

Marlowe published the unit as a chapter of a new textbook “Teaching Difficult Histories in Difficult Times” in collaboration with the UF African studies department on Feb. 11.

After more than a year of collaborating with UF to write this curriculum, Marlowe and other teachers piloted it in three African American History high school elective classes in Alachua County in 2021. This curriculum is now in every African American History class and made available to every 11th grade American history course in the county.

However, new bills in the state legislature seem to threaten the expansion of Black history education. Book banning, Critical Race Theory and discomfort based on race are a few topics discussed in Tallahassee.

Rehm said ACPS doesn’t anticipate current legislation to alter the current curriculum.

In Buchholz High School history teacher Morey’s class, students read African literature like “Things Fall Apart” and “Dreamland Burning.” If such books were to be banned, she said she would have to take them out of her curriculum.

She doesn’t want to stir that pot.

“All of that stuff,” Morey said of legislation circling the state legislature. “It has not impacted me. And, honestly, I bring the discussion of the history wars into class.”

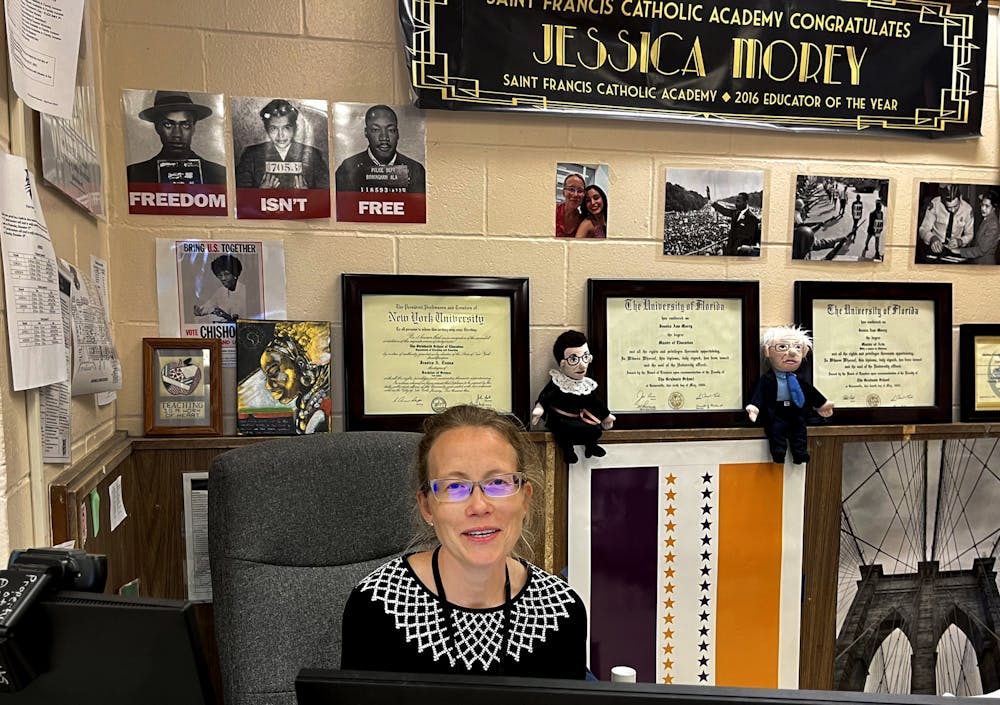

She brought a Wall Street Journal clip to class that discussed the arguments surrounding how history should be taught. Morey taught her students about the United Daughters of the Confederacy who pushed pro-Confederacy textbooks to teach the Civil War in a way that praised the Confederates. Morey teaches African American History, AP U.S. History and other advanced and honors courses. With a graduate degree in African history from UF, she jumped at the chance to teach the African American History elective three years ago.

Like Marlowe, Morey doesn’t follow the given curriculum. She believes each African American History teacher brings their own gifts and interests to the course, so each high school offers a slightly different style of learning.

“Because I’m trained as a historian, I treat it as a history course,” Morey said.

She teaches in chronological order, starting in Africa with colonialism and the Atlantic Slave Trade through the Civil War up to today.

The course has a textbook, but Morey doesn’t use it.

“It doesn’t really bring it to life,” she said.

She integrates primary and secondary sources, documentaries and literature to give her students an understanding of Black history.

Educators integrate Black history year-round

Beneath fluorescent lights, Morey’s classroom walls are plastered with newspaper clips and posters of civil rights movements. In the corner, a Joe Biden cut out stands in front of the rows of wooden desks. Her SMART Board projects the Canvas modules for this semester.

The public assumes African American History is not being taught in schools, Morey said, which is why she doesn’t just reserve it for her African American History elective or February.

“African American history is U.S. history,” she said.

This month, Morey’s AP U.S. history class discussed Marcus Garvey and his Pan-Africanism movement along with the re-rise of the KKK in the 1920s.

However, she can’t speak for every classroom.

“If a teacher is getting up there and using lectures they’ve been using for 30 years, they may very well not be teaching it,” Morey said. “And it’s also what type of learning have you had yourself?”

Some younger students receive Black history education outside of the repeated names of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, such as Caprice Blake’s 5-year-old daughter. She attends voluntary prekindergarten at the Caring and Sharing Learning School.

“Every day she has come and talked about a new person she has learned about involving Black history,” Blake said. “The normal stuff you will hear about is Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, but she has been coming home with people that I’ve never heard of.”

Blake’s daughter recited the poem “Hey Black Child,” a piece written during the Harlem Renaissance, during the Fall 2021 school year.

The Caring and Sharing Learning School is a charter school and not a public school under ACPS. Charters have access to the ACPS curriculum, but the individual schools decide whether to implement it.

To celebrate Black History Month, Eastside High School students and teachers crafted a periodic table of Black history with important figures instead of elements.

At the elementary level, third graders from Rawlings Elementary participated in a living wax museum to share what they had learned about Black figures like Misty Copeland and Jesse Owens.

ACPS will continue to teach Black history and seeks to pinpoint weaknesses in the current curriculum in an effort to improve.

Parents and passionate teachers believe Black history belongs in classrooms every month of the year. Educators like Marlowe and Morey exceed expectations, but all educators must be held accountable to avoid inconsistencies in curriculum application.

“There’s never a point where you can fully cover every single thing,” Rehm said, but ACPS aims to adapt its curriculum to best educate its students of Black history.

Contact Emma Behrmann at ebehrmann@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @emmabehrmann.

Emma Behrmann is a fourth-year journalism major and the Fall 2023 digital managing editor. In the past, she was metro desk editor, K-12 education reporter and a university news assistant. When she's not reporting, she's lifting at the gym.