Harold Stahmer will be remembered by the smell of books, cigars and turtles as well as his love of chocolate ice cream, at least to Hannah, his daughter. Others will remember him as a lifelong advocate for justice and equality.

Stahmer, a UF religion emeritus professor, died at 91 in Gainesville on Oct. 23 after a five year battle with Parkinson's disease. His actions and role in education left a memorable mark in his family and at UF.

“He was a pretty amazing dad,” his youngest daughter, Hannah Stahmer, 59, said.

His interest in civil rights led him to move to Gainesville in 1969 with the purpose of working on UF’s racial integration. He served as the associate dean of the UF College of Arts and Sciences until 1979 and continued working at UF until 1995 as a religion professor, Hannah Stahmer said.

Stahmer was a key figure in the establishment of the African American Studies Program created in 1969, according to its website. This happened after UF students went on strike in November 1968 demanding the inclusion of Black faculty and students and for Black courses, spaces and opportunities.

During his 26 years at UF, he also helped establish the Women’s Studies program, the Center for Jewish Studies, the Center for Gerontological Studies and the Criminal Justice program, according to a note published by the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Stahmer was born on Aug. 7, 1929, and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. A white man, he was active in the civil rights movement and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Alabama, in the summer of 1965, Hannah Stahmer said.

Stahmer wanted his daughters to find their own religion. He was spiritual, appreciative of all beliefs and passionate about teaching about them, Hannah Stahmer said. However, he did not follow any specific religion.

Stahmer wrote and published over 15 research articles and books in the fields of philosophy of religion, theology, and the Jewish-Christian dialogue, according to his curriculum vitae.

“He took people's beliefs very seriously,” Hannah Stahmer said. “And that carried over to how he felt about people — that everybody should be respected for what they believe.”

After graduating from Dartmouth College in 1951, Stahmer spent a year living as a monk at a monastery in Germany. There, he studied German, Latin and Roman Catholicism. He also interpreted Gregorian chants he would listen to until the last of his days, Hannah Stahmer said.

Amid the Vietnam war, Stahmer became part of a committee called “Committee of Responsibility” that would bring wounded children from Vietnam into American households. Children would go back to Vietnam if their families were found and relocated.

In 1968, Stahmer welcomed Yen Van Doan to his family’s New York home. He didn’t know English but learned and attended second grade with Hannah Stahmer. He eventually returned home to live with an uncle but felt like a brother to Hannah and her sisters — Sarah and Jennifer — during the two years they lived together, she said.

“Dad wanted us to experience things,” Hannah Stahmer said. “And I'm always grateful for that experience.”

Voting, defending his civil duties and sharing that with his daughters was important to him as a Democrat, Hannah Stahmer said.

“If we didn't vote — oh, my gosh, that was terrible,” she said. “The minute the Reitz Union opened the voting, I was like ‘I gotta go. This is for my dad.’”

Hannah Stahmer, who lives in Gainesville, would meet her father at the 43rd Street Deli on Sunday mornings. He would bring her a copy of the Gainesville Sun and one of The New York Times. He was a caring and loving father, she said.

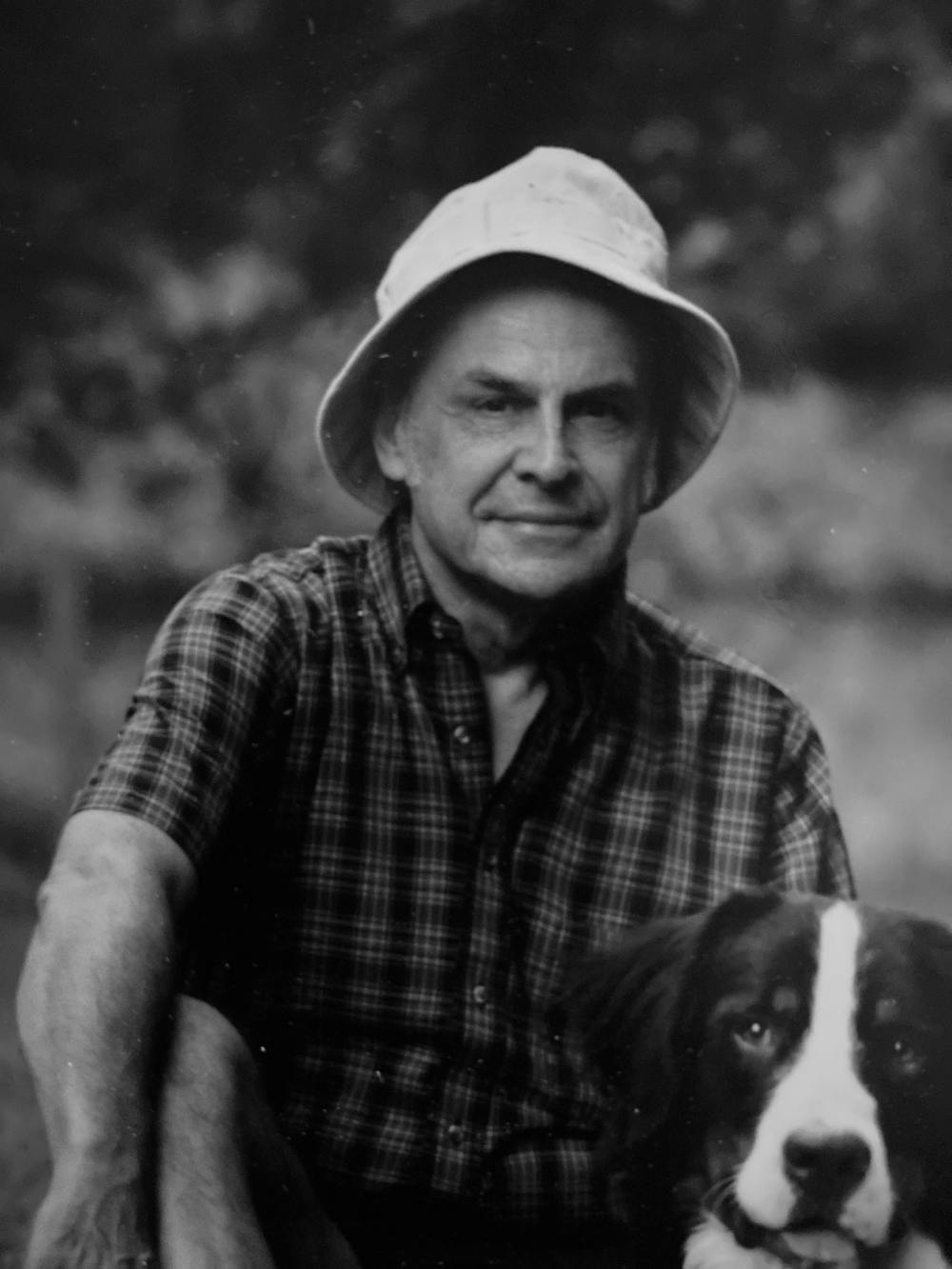

Stahmer was a handsome man who would always have a hat on — a cap, a fishing hat or a straw one, Hannah Stahmer said.

“He lived a good long life. He really did,” she said. “He had family that loved him and some people aren't fortunate to have that.”

Stahmer was married to Jean Smith from 1956 to 1982. In 1985, he married Paula Stahmer, with whom he lived until he died.

Paula Stahmer said he was very welcoming, had a huge heart, empathy for all humankind and tremendous energy.

“He could do by noon more than I could do in a week,” she said.

Together, in 1998, Stahmer and his wife were involved in the campaign for a charter amendment to save the Hogtown Creek surrounding environments, which include the Loblolly Woods and Hogtown Creek Headwaters parks, Paula Stahmer said. They succeeded with 59% of votes to protect the land flaking the creek, according to the Gainesville Sun.

When he died, he was with his daughter Hannah, Hannah’s two dogs and his own dog Pumpkin, a medium size dog, Paula Stahmer said.

“He knew where he was, and he knew what was going on, but he was weak,” Paula Stahmer said. “And then he just slipped away in his sleep.”

Stahmer died before Election Day but voted before with an absentee ballot. His wife brought their ballots to the Supervisor of Elections Office as soon as they could because Stahmer was scared they would get lost in the mail, she said.

Paula Stahmer wants to honor him by always taking care for others, speaking up and advocating for what is just, she said.

“He cared very much about other people and doing his duty as a human being and as a citizen to make the world a better place,” Paula Stahmer said.

Vasudha Narayanan, distinguished UF religion professor, worked with Stahmer from 1982 until he retired. The two became good colleagues and friends. She describes him as someone who fought for justice all his life.

Stahmer also had a wonderful, almost wicked sense of humor, Narayanan said.

He and his wife visited Narayanan after a major brain surgery she had in 2007. They were worried and brought her flowers and chocolates. Narayanan said Stahmer said to her “If you wanted chocolates, why didn’t you just say so? You didn’t have to go this far to get attention.”

“I remember laughing so much that my stitches hurt,” she said.

Although it was expected, Narayanan had a sense of sadness when he died. She said she wished she had spent more time with him during the last couple of years.

“He was a person of absolute integrity, brilliant, and with a sense of compassion and kindness,” Narayanan said.

Aurora Martínez is a journalism senior and the digital managing editor for The Alligator. When life gives her a break, she loves doing jigsaw puzzles, reading Modern Love stories and spending quality time with friends.