Danielle Chanzes’ eyes watered when her boyfriend called her from the Alachua County Jail for the last time. He was going to be freed that evening.

After hearing the news, she drove to the nearest Burger King and got him his favorite meal, a Whopper with fries. Ernest Walker, Chanzes’ 42-year-old boyfriend, was released from the Alachua County Jail on Nov. 3 after being held more than eight months without bond.

Chanzes, a 27-year-old activist, is fighting for restorative and rehabilitative criminal justice reform to reduce staggering recidivism rates, which is the rate at which convicted criminals become repeat offenders in Florida. Walker also advocated for others from behind bars, connecting inmates to Chanzes.

In January, Walker was arrested for violating the terms of his probation after being accused of vehicle grand theft.

He has a long history of incarceration, first serving a ten-year sentence in prison for a slew of charges, including battery and cocaine possession in 2003. Later, he returned to prison for another two-year sentence in 2012 for violating parole.

He also has been in and out of jail on petty charges since his last release from prison in 2014 — before his jail time in 2020.

Prison is where offenders serve their sentences after they’re convicted, while jail is where the accused await trial or sentencing. Walker was held in the Alachua County Jail for over eight months.

Walker’s story of repeated offenses is similar to that of many other former inmates. Between 2007-2015, more than one third of inmates released returned to Florida prisons within five years of their prison release date, according to data from the Florida Department of Corrections.

Chanzes is an organizer with the Florida Immigrant Coalition and formerly worked with the Legal Empowerment and Advocacy Hub. She now collaborates with lawyers as a courtroom advocate to help defendants get lesser sentences.

Often at the jail protesting for criminal justice reform, night shift guards instantly recognized Chanzes when she went to pick up Walker that brisk 50° night, she said.

She said she believes that the U.S. criminal justice system leaves vulnerable people behind.

“The people that end up incarcerated are hurt people,” Chanzes said. “Hurt people, hurt people. These are people with unresolved trauma who are dealing with mental health issues and addiction, sometimes even acting out of survival.”

If someone had intervened and addressed his mental health and addiction issues earlier in his life, Chanzes said she thinks Walker wouldn’t have had to serve 12 years in prison.

“This is an issue that is personal to me,” Chanzes said. “I hope others don’t wait until it becomes personal to them.”

Syraj Syed is a narrative counseling specialist at Your Authentic Self Work, a counseling service that aims to empower individuals and organizations towards conscious growth by owning their life’s narrative. He works with Walker and others formerly incarcerated to address their traumas.

In January, Syed began to counsel Walker while he was still incarcerated both on video chat and in person.

“In a poetic sense, it’s to help them see the boundaries of the prison they exist in,” he said. “Not one of bricks and steel, but one of the mind.”

Syed has also worked with the Legal Empowerment and Advocacy Hub and attended a national participatory defense retreat with Chanzes. He noted the deep connection she felt to Fox Rich, a woman who fought for her husband’s release for decades and is now the subject of “Time,” an Amazon Prime documentary.

“That’s what Danielle has in her,” Syed said. “It’s intrinsic.”

Chanzes said the couple has been inseparable since they met in 2018.

They met while Chanzes was registering voters in East Gainesville’s Duval Heights neighborhood with the Florida Immigrant Coalition, she said.

The couple didn’t see each other for a while after that day, Chanzes said, until she returned a month later to register more voters and heard someone honking their car horn at her. It was Walker.

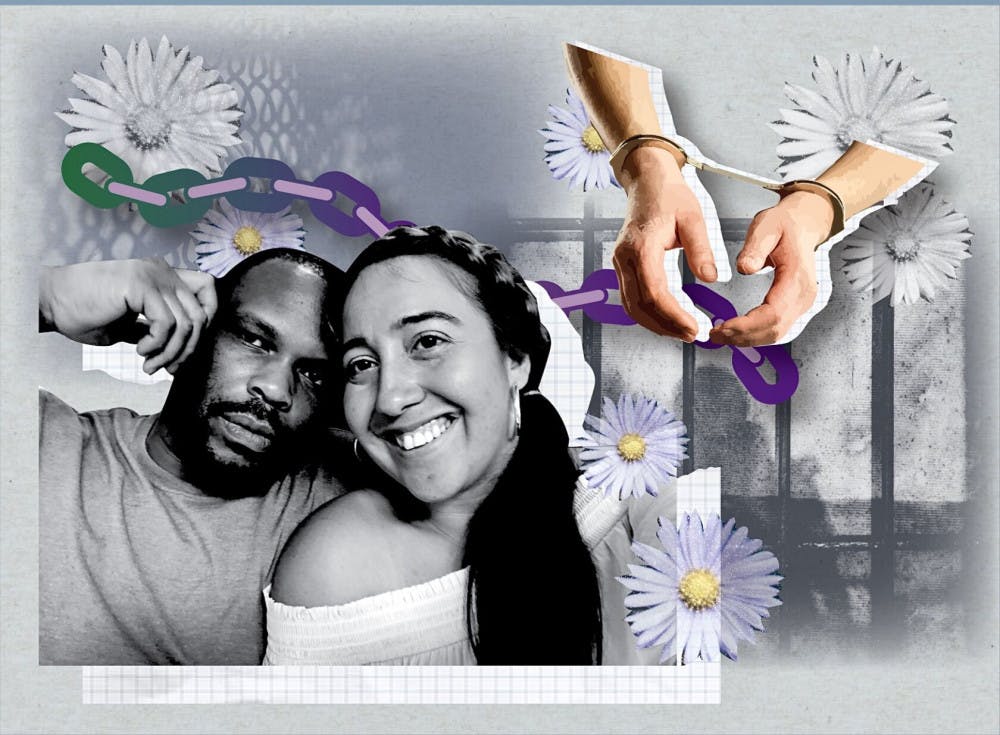

Danielle Chanzes, 27 came to visit her boyfriend Ernest Walker, 42, in Oct. 2019 outside the Sid Martin Bridge House, a residential substance abuse treatment program.

Chanzes was by his side during his hearing, too.

Walker chose an open plea, which meant that his fate was entirely at the hands of the judge. He said it was difficult to hear the prosecution attack his character.

“It intrigued me that he was able to stand up there for seven or eight minutes about how much I’m a bad guy when he’s only met me twice in court in front of a judge,” he said.

Walker said he’s grateful for the leniency the judge showed him because he expected to have been sentenced to up to six years in prison. Chanzes and a team of community activists supported him through the hearing, he added.

While in jail, Walker said it felt as if time was frozen even though the world kept turning.

“When I was released, it was sort of a stillness, a quietness and a sense of peace that came over me,” he said. “On the inside of jail it’s these cold gray walls, and everything echoes. Everyone talks too loud. Just to be released — that was a blessing.”

What Walker missed most all those years, he said, was not being able to see his three children grow up into teenagers.

While at the jail, Walker organized for Chanzes’ 352 Freedom Fund from the inside, connecting activists to harder-to-reach inmates.

“I’m just her sidekick,” he quipped.

Walker said helping inmates get released from the jail was an effort ordained by God. Many inmates offered to repay him for his help, but he only asked them for one thing — to make the right choices.

After being in and out of prison and jail for almost two decades and spending more than eight months in a bleak jail cell, Walker said he can’t picture reverting to his old way of crime, drug use and evading the police. He said he’s now taking the time to learn healthy habits.

He said he’s overcoming addiction through Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings and therapy. He also meets with the Torchlighters Re-Entry Support group, where former inmates share their struggles adjusting to life in the free world. The group is organized by Community Spring, a Gainesville-based organization with a goal of dismantling structural poverty.

“My nine to five was clocking into the streets,” Walker said. “Intensive therapy is something that I welcome. Every day is not going to be a good day, but this is something that I need.”

Hope Johnson is an organizer with Community Spring and co-founder of the Torchlighters Re-Entry Support group where she regularly works with Walker. In her life, she said she’s had relatives behind bars. She met Chanzes while attending a meeting for the family members of incarcerated individuals.

Johnson first saw Walker in person in the courtroom, where he was brought out in handcuffs and a striped jumpsuit. The image, she said, reminded her of slavery.

She regularly works with Walker through the support group and said she believes he’s putting in the work to listen and learn, often taking detailed notes.

“I find myself at ease just realizing that I’m not just here to help Ernest,” Johnson said. “I’m here because it’s saving my life knowing that I’m helping to save yours.”

Focused on rebuilding his life, Walker hopes to become an activist, mentor and motivational speaker.

Walker pointed to how he’s seen firsthand how hard it is for former inmates to readjust to society, mentioning how many go on to experience homelessness. Usually they become repeat offenders.

“What I’ve learned is that I have to crawl before I can walk and walk before I run,” Walker said. He sees readjustment like wearing a gas mask during an emergency on a plane. It’s not possible to help others without placing one’s own gas mask on first.

To Chanzes, the criminal justice system should address the needs of people who commit crimes instead of defaulting to lengthy prison sentences. Everyone in the community has value, she said, no matter their record. After organizing from behind bars, Walker said he will join Chanzes when he feels ready and able.

“We shouldn’t address their issues by throwing people in cages, locking them up and throwing away the key,” Chanzes said. “Justice doesn’t have to be punitive or carceral, it can be restorative and transformative. If we want safer communities, that’s the way we have to do it.”

Alan Halaly is a third-year journalism major and the Spring 2023 Editor-in-Chief of The Alligator. He's previously served as Engagement Managing Editor, Metro Editor and Photo Editor. Alan has also held internships with the Miami New Times and The Daily Beast, and spent his first two semesters in college on The Alligator’s Metro desk covering city and county affairs.