Using African American Vernacular English as a Black person is expected and encouraged but also criticized.

While AAVE words and phrases, “sis,” “lit,” “yas” and “tea” have become popular online, many Black students who speak AAVE aren’t understood and sometimes even ridiculed by teachers. In the American education system, Black students may speak AAVE, which some teachers consider incorrect because of its different speaking and writing patterns.

The debate about AAVE’s validity even led to a successful lawsuit against school systems in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1979, after teachers denied AAVE’s existence. Oakland, California, recognized AAVE as a language in 1996.

Expert linguists, like Diane Boxer, a UF linguistic professor, said AAVE is a highly developed, systematic language with its own predictable grammatical rules.

AAVE is a language variety essential to Black culture, Boxer said. The variety, which has its own grammar, vocabulary, syntax, pronunciation, word forms and context, was formerly known as Black English Vernacular or Ebonics.

The variety grew after slave owners purposely grouped slaves from different areas of Africa so that they couldn’t understand each other, Boxer said. The rise of the variety began as a pidgin language, which develops when two speakers don’t share a common language.

While most speakers of AAVE acquire it by hearing it at home while growing up, linguists like Boxer believe it isn’t something that can be taught.

Bidialectal students are similar to children who grow up bilingual, Boxer said. Speakers of AAVE grow up with one way of talking in their community and another way of talking in formal situations. The situation differs because AAVE speakers are usually exposed to English.

However, Boxer said students may not find using standard English necessary — this is where they may find educational trouble.

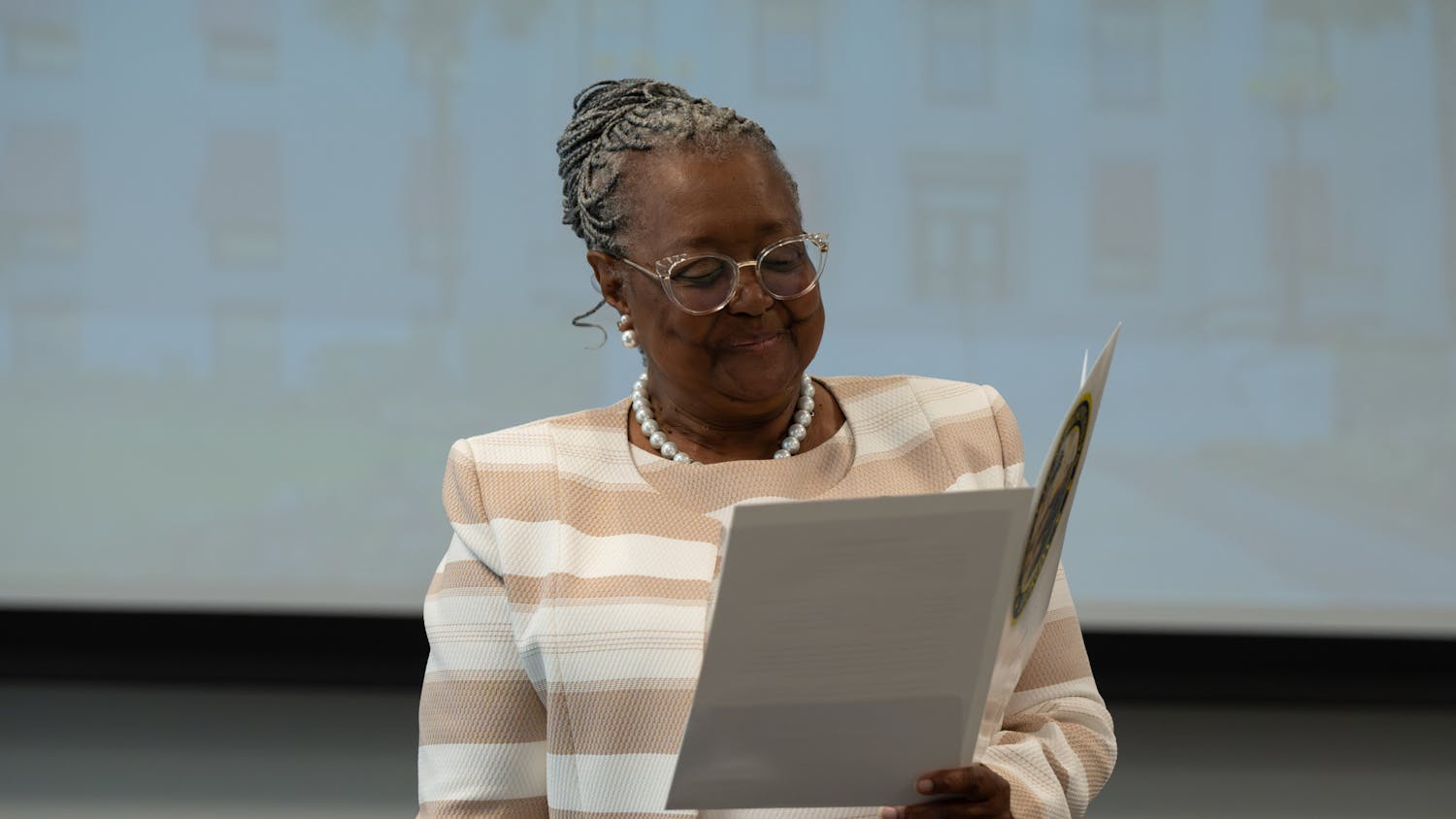

Students in Davida Holmes’ English classes at Eastside High School sometimes used words often perceived as slang, like “finna,” “gon’” and “ion.” Holmes, their teacher said she never bashed them or told them they were wrong.

Many of the students in her classes were fluent speakers of AAVE, so few students using standard English when writing papers can have experiences comparable to those learning English as a second language, Holmes said.

Holmes, who taught general and Advanced Placement English courses, had her students read books that combine AAVE and SAT prep words with a standardized writing style. Her students read The Hoopster Trilogy by Alan Lawerence Sitomer, a novel about a young Black basketball player navigating racism while pursuing journalism.

When growing up, Holmes said her mother wouldn’t allow her and her siblings to use AAVE until they knew standard English. Her mother said if she wanted to use a phrase like “Ion like that” or “I’m finna go to the store,” she needed to know how to say “I’m not going to do that” or “I’m getting ready to walk to the store.”

“It was not a matter of learning a foreign language per se,” Holmes said. “I think it was more so my mother just telling me ‘This is the way that you’re expected to speak within society and be respected, so you gon’ do it.’”

People who say the variety is grammatically incorrect are misinformed, insensitive and dismissive of Black history, Holmes said. However, she added that many students told her they felt they were perceived as ignorant or stupid because of the way they spoke.

“I think language has a way of doing that,” she said. “I think it has a way of making people feel like they’re inferior or superior to others, and that is why I teach the way that I teach my students.”

When she felt relaxed, Holmes said she used words like “finna” in classes.

This is called code switching, or the swap from one language variety to another, Boxer said. AAVE speakers everywhere do it every day.

AAVE speakers may code switch to be recognized as a member of a cultural group, Boxer said. A Black person may be seen as an outsider to the culture if they don’t speak like those around them in informal situations. The change, often a subconscious one, involves shifting all aspects of language — grammar, vocabulary, tone, intonation, diction and pitch and volume — depending on what someone is trying to say, she said.

As a code switcher herself, Holmes said students have asked her how she learned to talk differently even telling her that she “talks white.”

“It’s almost like you’re a chameleon,” Holmes said. “You need to be able to adapt to the situation that you’re in, OK?”

To Boxer, teachers need to adapt as language evolves.

“Language is always in the process of changing,” Boxer said. “It’s not accepted by the wider public, especially people who are in the teaching profession who ought to be able to accept different varieties of English.”

While most speakers of AAVE acquire it by hearing it at home while growing up, linguists like Boxer believe it isn’t something that can be taught.

Asta Hemenway is a third-year senior majoring in Journalism. Born in Tallahassee, she grew up Senegalese American. When she’s not writing or doing school, she loves watching Netflix and Tiktok in her spare time.