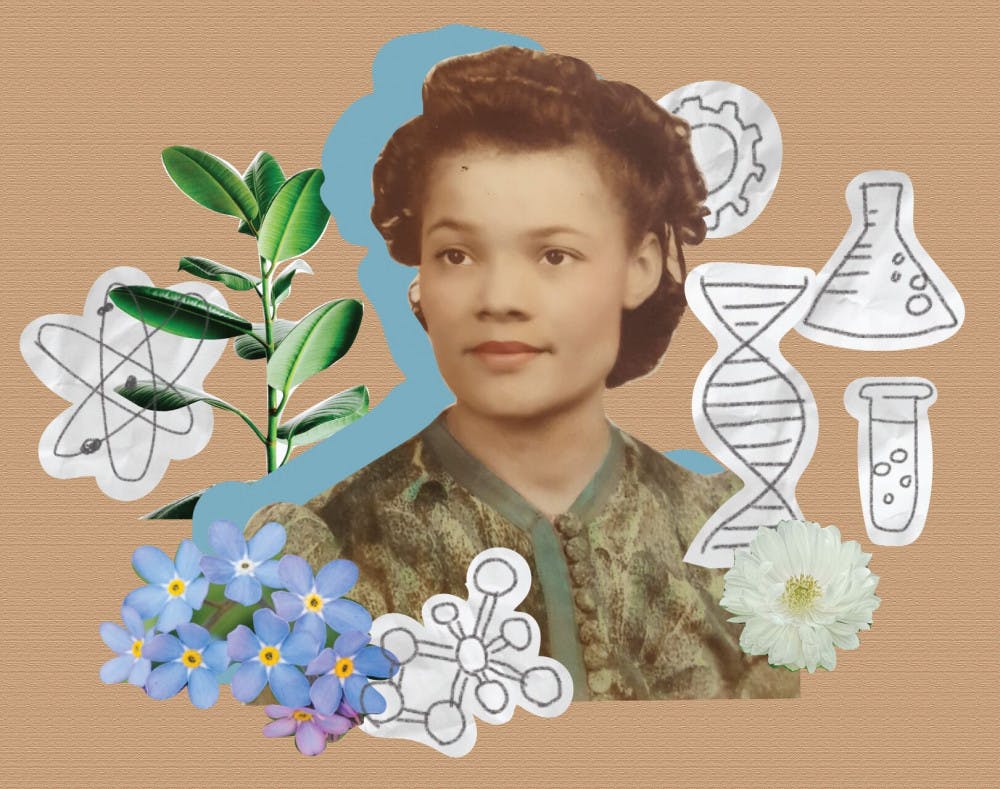

She was born in the Jim Crow South. At 20, she dedicated her life and mind to protecting all Americans, even those who oppressed her, from the threat of Nazism. She was the first African American woman in the U.S. to receive a graduate degree in physics — later earning another master’s degree in the field.

The Alachua County School Board’s renaming committee voted to approve the new namesake for J.J. Finley Elementary School: Carolyn Beatrice Parker. The school’s current namesake was a confederate soldier and is known for his contribution to the culture of lynching in Alachua County.

The Alachua County School Board voted to rename the school Carolyn Beatrice Parker Elementary School officially on Tuesday, Committee Chair Carlee Simon said.

“Not only was she incredibly successful academically, and she came from a very successful family, but she also was successful in, even now, a predominantly male-occupied field of study,” Simon said.

Born in 1917, Parker grew up in Gainesville’s Jim Crow era, said Peggy Macdonald, a renaming committee member, Stetson University history professor and author of a biography about Parker. While she was an infant, her father, a physician, worked to eradicate the influenza epidemic of 1918.

According to Macdonald, six of Parker’s seven siblings achieved advanced degrees. Her sister Julia Leslie Cosby became the first Black woman to teach in the previously all-white Alachua County schools.

Parker’s niece, Dr. Joyce Cosby, has fond memories of Parker, who passed away when Cosby was 10. She remembers her mother calling Parker her favorite sister.

After high school, Parker taught in Rochelle, Florida, with her sister for a year to save money for college, Cosby said.

Parker later moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to pursue a bachelor’s degree in physics at Fisk University. She graduated magna cum laude in 1938 before returning to Gainesville to teach alongside her mother for two years, Macdonald said.

While Parker’s name is not listed in Kevin McCarthy and Albert White’s 2012 “Lincoln High School, Gainesville, Florida: Its History and Legacy,” Macdonald said she, her colleagues and Parker’s nieces believe she taught at Lincoln High School.

In the 1940s, the historically Black Lincoln High School was the only Gainesville institution that would have permitted Parker’s service.

In 1941, Parker made history when she became the first African American woman in the U.S. with a graduate degree in physics, which she obtained from the University of Michigan. Ten years later, Parker almost earned a Ph.D. in physics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

However, she put her education on hold two years later.

She was welcomed to the Dayton Project, a division of the Manhattan Project, which created the American atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, Macdonald said. Her division was recruited to work with polonium, a highly radioactive element used in atomic bombs.

“She contributed to ending World War II, working on a project that was originally designed to defeat Hitler,” Macdonald said.

Albert Einstein informed Franklin Delano Roosevelt that the Nazi scientists were verging on finalzing the atomic bomb, and the Manhattan Project was founded in response, Macdonald added.

While working on the Dayton Project, Parker would have experienced numerous levels of oppression, Macdonald said. During the early-to-mid-20th century, women in science were usually given menial tasks despite their potential, she added.

“What Carolyn Parker did was incredibly uncommon for a white woman scientist,” she said. “To be an African American and female scientist and this time, the challenges she surmounted were incredible.”

According to the renaming committee’s proposal and biography, the Black scientists working for the Manhattan and Dayton Projects were commonly mistaken for janitorial staff.

While the goal of the projects is now known, the work was top-secret at the time, and Parker’s family still doesn’t know the extent of their ancestor’s work, Macdonald said.

According to MIT Black History’s profile on Parker, she couldn’t discuss her job with her family.

However, the work Parker did wasn’t disclosed to her and many of her fellow scientists, Macdonald said. The deployment of the bombs using elements they studied was a shock to them.

Because Parker was a junior scientist, she didn’t participate in the decision-making of dropping the atomic bomb, according to the renaming committee’s proposal.

After leaving the Dayton Project in 1947, she worked as an assistant physics professor at Fisk, even though women were discouraged from teaching advanced science courses, Macdonald said.

Fisk University is a historically Black university, but she still had to overcome barriers as a minority — women at the time were commonly not permitted to teach science.

Parker earned a second master’s degree in physics, and she was on track to become the first African American woman to receive a PhD in physics.

She continued her work in research as a physicist for Air Force Cambridge Research Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, after receiving a second master’s degree in physics from MIT, Macdonald said.

Before having the chance to defend her doctoral dissertation, tragedy struck.

Parker died from leukemia in 1966. In 2008, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health declared that polonium can cause cancer.

“I really felt sympathy for this amazing woman, who completed work that most female scientists could not have done,” Macdonald said. “And yet she was working to save the nation from Nazi threat of attack. Then because of her work to do that, she died from leukemia, so she really sacrificed her life to save the nation during World War II.”

Parker is buried in Mt. Pleasant Cemetery in Gainesville among other important Black national figures like Matthew Lewey and the wife of Josiah T. Walls, Macdonald said.

Parker’s family still attends church services at Mt. Pleasant Methodist Church, she added.

While her story wasn’t told for years, the renaming committee hopes that the school board will take this opportunity to unveil Carolyn Beatrice Parker’s hidden history, Simon said.

“There are these pieces of our history that I think many of us are being introduced to pretty late in our lives,” Simon said. “And it's so unfortunate that we didn't know certain things sooner, and it wasn't part of our curriculum and it wasn't a cultural component of American life.”

According to Simon, some Alachua County Public School teachers are already excited to include Parker in their curriculum. The committee also discussed holding a science fair in her name.

As an elementary-school-aged girl, Cosby lived in the J.J. Finley school zone. The school she once could not attend will now pay tribute to their family name.

“With the emphasis on science technology and math in today's era, certainly the fact that this was a woman who predated some that have received a great amount of publicity recently, namely the “Hidden Figures” — she was 20 years ahead of them.”

Macdonald reflected on what else Parker could have contributed to the U.S., science and history if her life hadn’t been cut short.

“There's so many ways you could teach national history major topics and themes through Parker’s life,” Macdonald said. “And her life was unfortunately brief — had she lived past the age of 48, I would like to think of all the other stories that we could tell about her.”