Doctors have to hand-draw maps of the brain to detect Parkinson's. However, sometimes this method can lead to misdiagnosis.

This may change after a research team led by a UF professor engineered a non-invasive technology that automatically diagnoses Parkinson’s disease. The work was announced on Aug. 28.

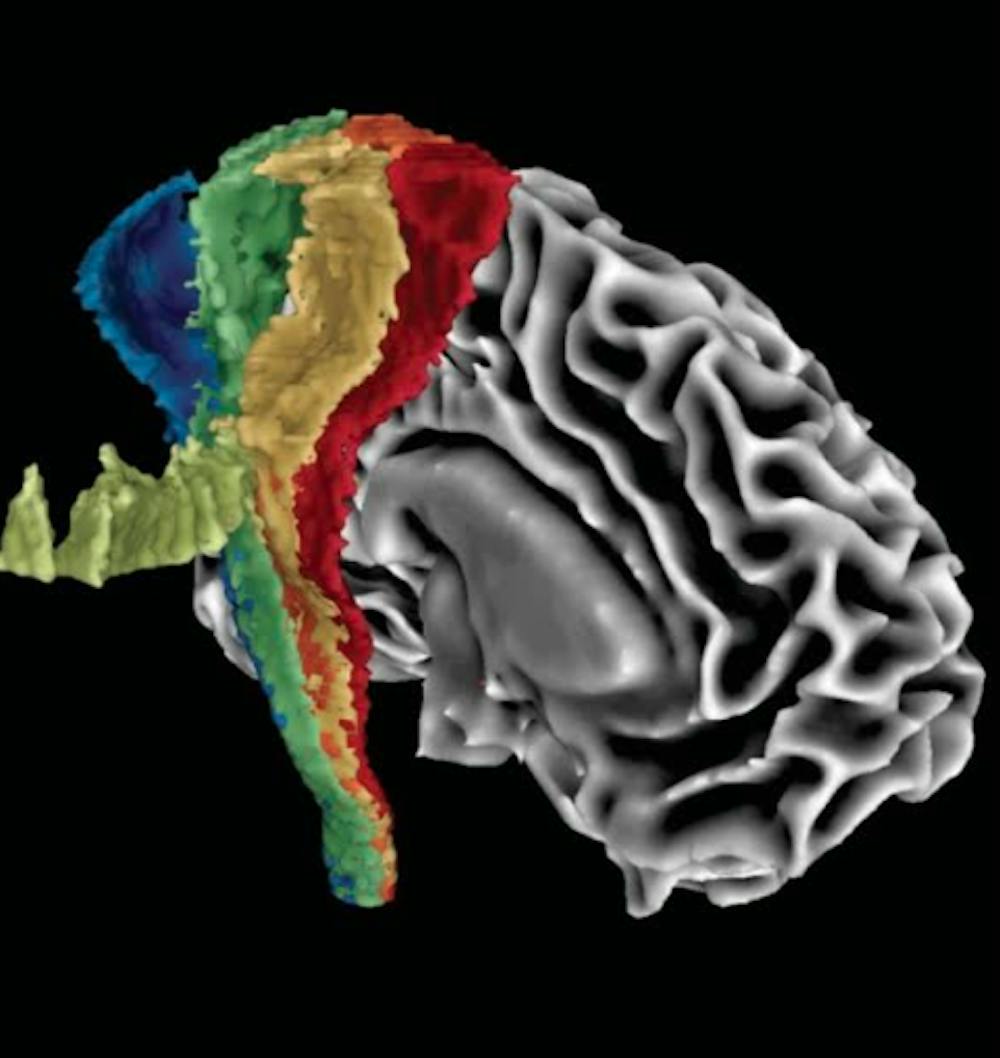

Led by David Vaillancourt, UF department chairman of applied physiology and kinesiology, the research produced an automatic imaging system that uses MRI methods to diagnose Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.

This system, called automated imaging differentiation of parkinsonism, should prevent misdiagnosis of Parkinson’s and similar diseases, Vaillancourt said. The current process to diagnose the disease involves drawing out brain areas by hand.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, took place over about two years and involved 1,002 patients in 17 facilities in the U.S., Austria and Germany, Vaillancourt said.

He said this could change the industry.

“Patients are misdiagnosed early on,” he said. “They are misdiagnosed and end up having an atypical form of Parkinsonism, but each of these diseases have different treatments and clinical courses.”

The researchers do not know when the technology will be available to patients because this requires additional funding that has not yet been secured, he said.

Derek Archer, a UF post-doctoral research associate, was the project’s lead writer. The research team began work on the mechanical aspects of the project in 2015 and continued to this year, he said.

“The most rewarding part was the automated learning part,” Archer said. “A lot of clinicians can’t use MRI data quantitatively. We’ve created an automated pipeline that essentially they can just collect this image and it can give clinicians a probability of a patient having Parkinson’s.”

Winston Chu, a 26-year-old UF biomedical engineering doctoral student, assisted with the research scripting and programming. He helped create the computed algorithm that shows what patterns in the brain are most important in identifying Parkinson’s.

In today’s current medical practice, no software can pinpoint areas of the brain affected by parkinsonism and its atypical forms, he said. This new system has made this process possible and automated.

The difference in scans is so subtle that before this system was developed, it was difficult to distinguish between them with the hand-drawn brain maps, Chu said.

Having a centralized platform where other research groups could upload their images and clinical trial data would help this model to become more updated in the future, according to Chu.

“I think it is important to support biomedical research,” Chu said. “The more we can fund these kinds of studies the faster we can get to curing these diseases.”

Derek Archer developed a template to differentiate between Parkinson's and related diseases, illustrated here as used in the research team's automated imaging differentiation of Parkinsonism machine.