Evergreen Cemetery’s first burial was a 10-day-old baby.

James and Elizabeth Thomas lost their child and laid her near a cedar tree. What started as a single grave now lies at the center of a 53-acre cemetery in Gainesville filled with a variety of trees and memories.

Prominent local politicians, UF faculty, veterans, influential community members and local residents all rest in the cemetery, said Karen Pruss, the cemetery coordinator. As part of The Alligator’s yearlong Who is Gainesville? The project, which covered the past, present and future of Gainesville, we looked into Evergreen Cemetery and some of the people buried there.

In 1866, James sold more than 700 acres to residents Watson Porter and William Cessna, Pruss said. The cemetery was privately owned by several community members until 1944 when Gainesville purchased it.

“It’s just a wondrous place. It’s a calm, peaceful, beautiful, tree-covered place,” Pruss said.

In addition to prominent local citizens, more than 1,000 veterans who served in wars since the 1800s lie in Evergreen Cemetery, Pruss said.

Mausoleums and tombstones of various sizes and shapes dot the cemetery in contrast to the flathead stones of other cemeteries, Pruss said.

Among the prominent community members buried in Evergreen Cemetery are Thelma A. Boltin, Dr. James Robert Cade and Dr. Sarah Lucretia Robb.

These are their stories.

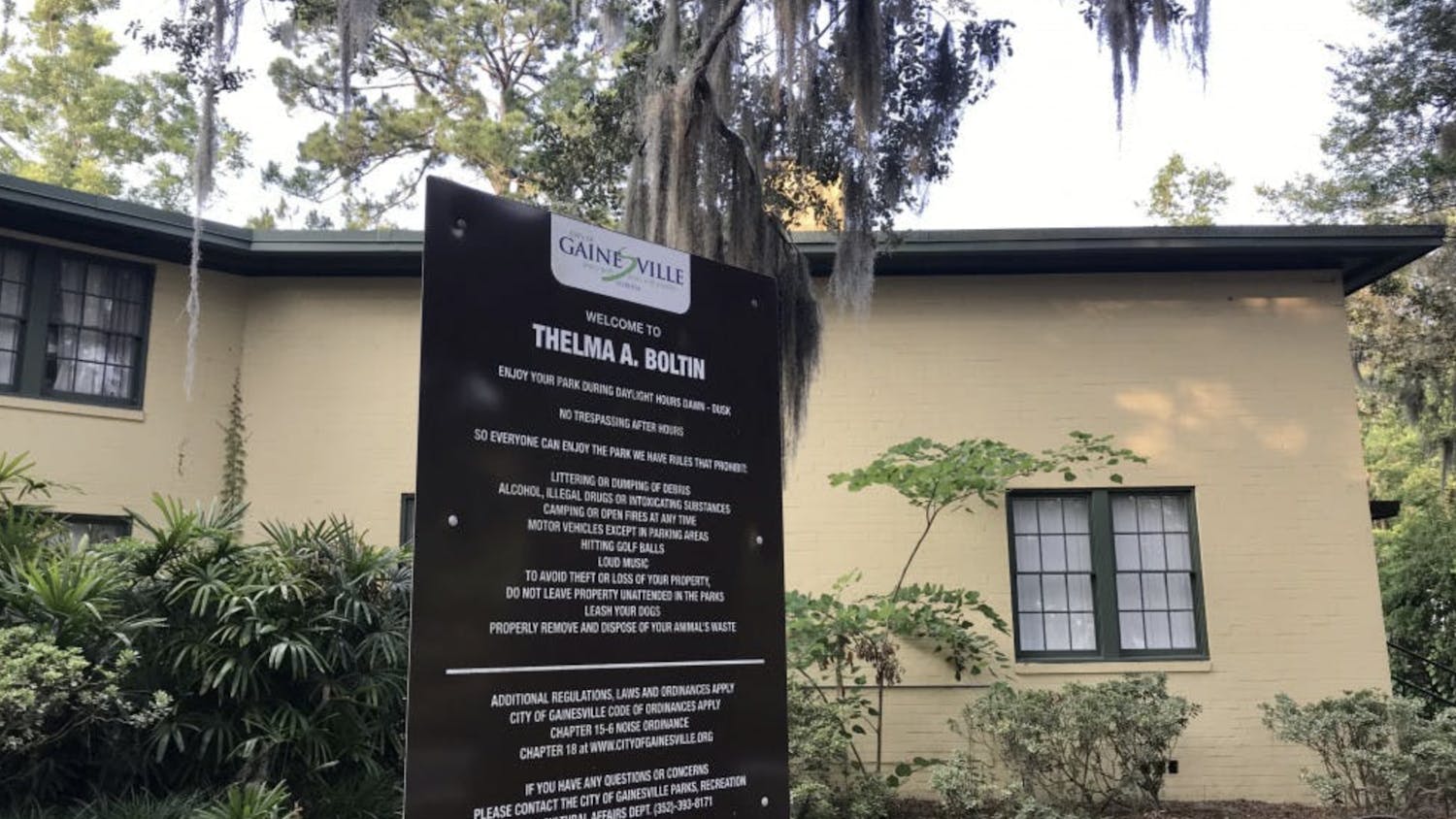

Thelma A. Boltin

Thelma A. Boltin was called Cousin Thelma by those who knew her. Her relationship with community members was close enough to be considered family.

Boltin moved to Gainesville at about 3 years old and left her legacy on the area through her storytelling.

She was an expert in folklore, teaching and performance, said Kim Rivers, a park ranger for Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State Park.

After studying English, drama and speech at Emerson College, she returned to Gainesville and delved into local folklore like no one had before, Rivers said.

“One of the things she did as a storyteller was not just to learn the stories and the folklore, but she collected and shared them so that they wouldn’t die,” Rivers said.

Boltin was a drama teacher at Gainesville High School and Florida’s first certified high school public speaking teacher, Rivers said.

She helped found Gainesville’s Little Theatre, where she also acted and directed.

She organized a teen club at a recreation center which stayed active from 1943 to the 1960s. It was renamed the Thelma A. Boltin Center in her honor.

Boltin was the director of the Florida Folk Festival from 1954 to 1965. She traveled the state on a Greyhound bus year after year to find new talent for the festival, Rivers said.

“She is referred to as the queen of Florida folklore,” Rivers said.

Rivers knew Boltin near the end of her life and was recently tasked with researching Boltin through archives to visually display at the park’s antiques, arts and collectibles event.

Rivers remembers her white outfits, bonnets and distinctive laugh.

“When they made Thelma Boltin, they made her unforgettable. And for that reason, she’s still talked about,” Rivers said. “She’s our legend. She’s our legacy.”

Dr. James Robert Cade

Gatorade bottles are one of the many ways James Robert Cade’s presence is still felt in Gainesville and around the world.

The former UF renal medicine professor and Gatorade creator was skilled in research, music, invention and medicine.

Mark Segal, the chief of the Division of Nephrology, Hypertension and Renal Transplant, worked with Cade when he was tasked to review his research for Institutional Review Board approval.

Cade brought an innovative and systematic approach to his work as a physician and researcher, which is why The Cade Museum for Creativity and Innovation is named after him, Segal said.

When creating Gatorade, Cade tested many variations so the drink would replace nutrients athletes deplete while exercising.

Cade was generous both within and beyond UF, even when he was low on funds, Segal said. Early in his career at UF, he purchased a dialysis machine for the hospital when the hospital would not spend the money on it.

“Without the money that Gatorade brings to the university to support research, you wonder if UF would be what it is today without that Gatorade money,” Segal said. “Certainly, it has had a profound effect on the College of Medicine and our department.”

After Cade retired, many of his patients were passed onto Segal, who is now the J. Robert Cade professor for Medicine.

“Every day, I try to live up to the legacy that he left,” Segal said. “He was the embodiment of everything that we try to be as physicians and as division scientists.”

James Bledsoe Bailey

A veteran, slave owner and politician is buried in the Evergreen Cemetery along with his daughter.

He was brought up in Montgomery, Alabama, fought in the Second Seminole War, returned to Montgomery and then moved to Gainesville.

The Second Seminole War saw guerilla attacks and many civilian casualties, said Sean Patrick Adams, a UF history professor.

“It’s really interesting that he fought in the war and then came to Gainesville,” Adams said. “It was not only an unsuccessful war, and it took a long time and a lot of lives. There was a lot of suffering on both sides.”

Upon moving to Gainesville in the early 1850s, Bailey became involved in local politics and helped bring Alachua County’s seat to Gainesville.

Gainesville’s immediate rise was influenced by the development of the Florida Railroad, Adams said. Gainesville became a prominent city when it became a stop along the rail line.

“Gainesville came into being in a really interesting time in the state’s history and in one that it’s hard for Floridians now to envision the way the state was,” Adams said. “Gainesville was considered one of the southern extreme towns in Florida.”

Dr. Sarah Lucretia Robb

Sarah Lucretia Robb was rejected by medical schools in the U.S.

Rather than staying a nurse, she got her degree in Heidelberg, Germany.

When she came to Gainesville in 1882, Robb was a general doctor and delivered babies. Midwifing was traditionally a female job without formal training but with experience, Adams said. Men at the time pushed women out of the industry despite their lack of practical knowledge.

“Women were really limited in what they could do in so many ways and one of them is in the professions,” he said. “You had a whole generation of women who couldn’t achieve what they wanted to achieve for that reason.”

Robb saw patients in her home, which is now the Robb House Medical Museum and Alachua County Medical Society, said Florence Van Arnam, the museum curator. She later saw patients as a traveling doctor via horse and buggy.

Robb was active in civic and church affairs, Van Arnam said. She started one of the first private boarding schools in Gainesville.

Robb and her husband co-authored a book of medicine, “Robb’s Family Physician.” In this book, they presented their contrasting approaches to medicine, Van Arnam said. Robb was a believer in a scientific approach to medicine, whereas her husband supported a natural approach.

“They were way ahead of their time,” Van Arnam said.

The Robb House Medical Museum is the first medical museum in Florida recognized by the American Museum Association. It holds aspects of her original household and over 1,000 artifacts.

“I would say she was one of the first emancipated ladies,” Van Arnam said.

Evergreen Cemetery had its first burial in 1856. The cemetery is now 53 acres large and prominent local figures such as politicians, veterans, teachers, professors and community members rest there.