The streets of Gainesville looked like a warzone in the summer of 1968.

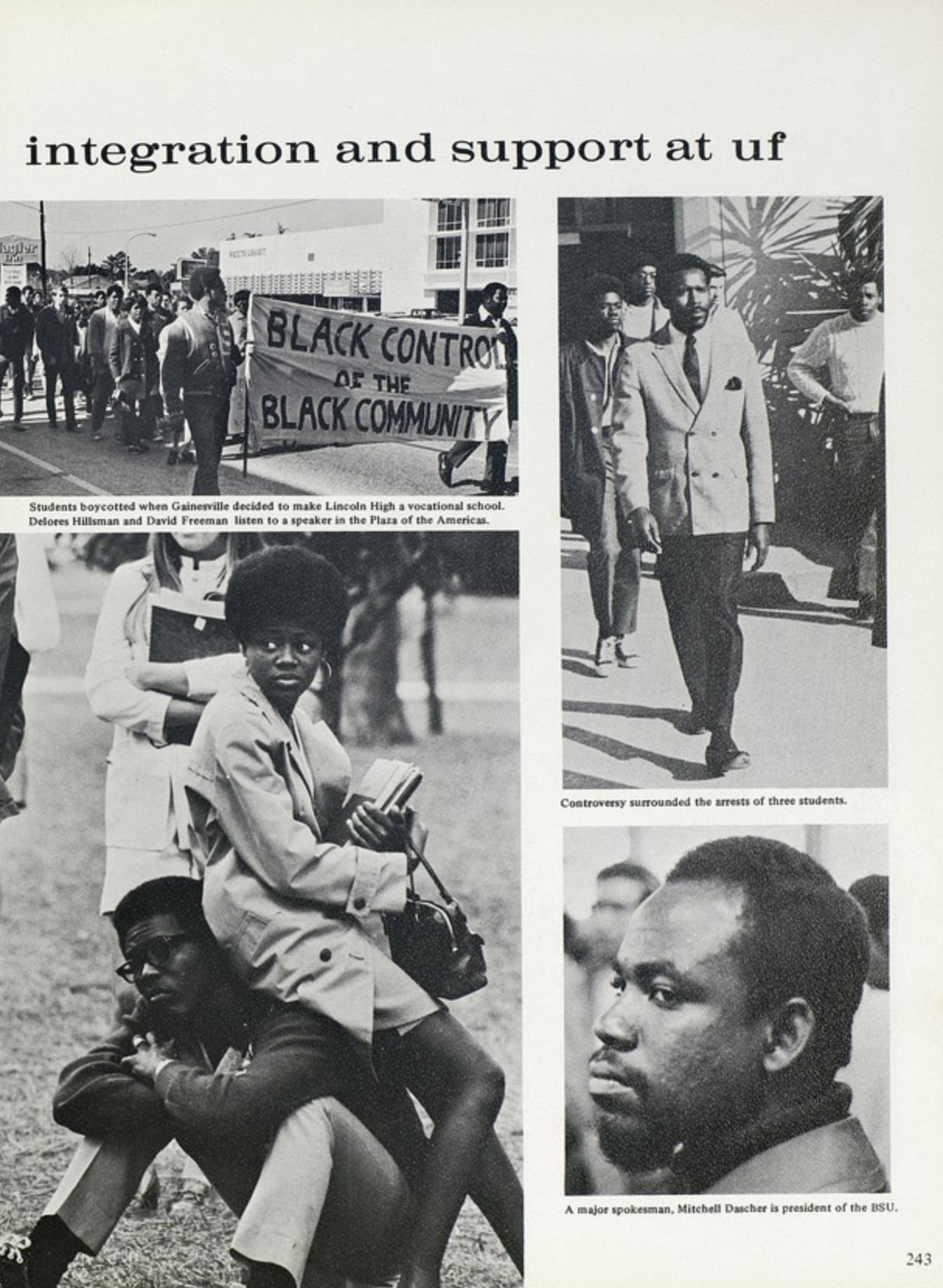

The City Commission enacted a nightly curfew from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. for all students and residents. Police arrested black power militants for inciting riots. National Guard troops patrolled downtown armed with rifles.

After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968, UF’s 87 black students began to confront white students and professors about improving race relations on campus.

The following year, the African American Studies program was founded. Now, the program is in its 50th year and beginning its transition into a department.

UF will become the first Florida public university with an African American studies department.

An archival article of The Alligator reports on the proposal for a UF African American Studies program on Aug. 1, 1969.

Mary Watt, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences College associate dean, said though it is uncertain when the program will become a department, a director may be hired by August. The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences is interviewing candidates.

A program is a collection of courses that compose a major or minor while a department is a unit of faculty for a specific academic specialty.

“This is a happy coincidence that this is happening in time for the 50th anniversary,” Watt said. “What better way to mark an anniversary than with the creation of something new?”

Watt, who oversees the search for a department director, said the benefits of becoming a department include tenured faculty and master’s and Ph.D. programs. Funding cannot be determined until the faculty and director are hired and their salaries are determined.

UF’s program originated in 1969 partially as a response to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Robert Kennedy and Malcolm X, African American Studies Director Sharon Austin said.

Prejudiced incidents on campus have occurred over the past half-century and continue to happen, Austin said.

Black students in 1968 told The Alligator that the discrimination they faced was “very subtle and difficult to prove.”

In 2017, racially charged incidents on campus still surfaced. UF President Kent Fuchs responded to a noose found on campus in January that year and acknowledged that the object is a painful symbol for the black community despite the intent of its appearance being unknown.

In February, someone uprooted the Walker Hall sign, which marks the home of the African American Studies program. Some interpreted this as an act of hate speech, but others saw it as a “drunken joke.”

In October of the same year, white supremacist Richard Spencer spoke on campus. About 2,500 people protested his presence.

One minority student was turned away from the event for having emergency contact numbers written on her arm. One student who attended the speech as a Spencer supporter said he believes in segregation. One man showed up wearing a T-shirt decorated with swastikas.

William Walker, a 24-year-old UF African American studies 2017 alumnus, said some of these incidents being close to Black History Month made him feel like black students were targeted on campus decades after the racial turmoil in the ‘60s.

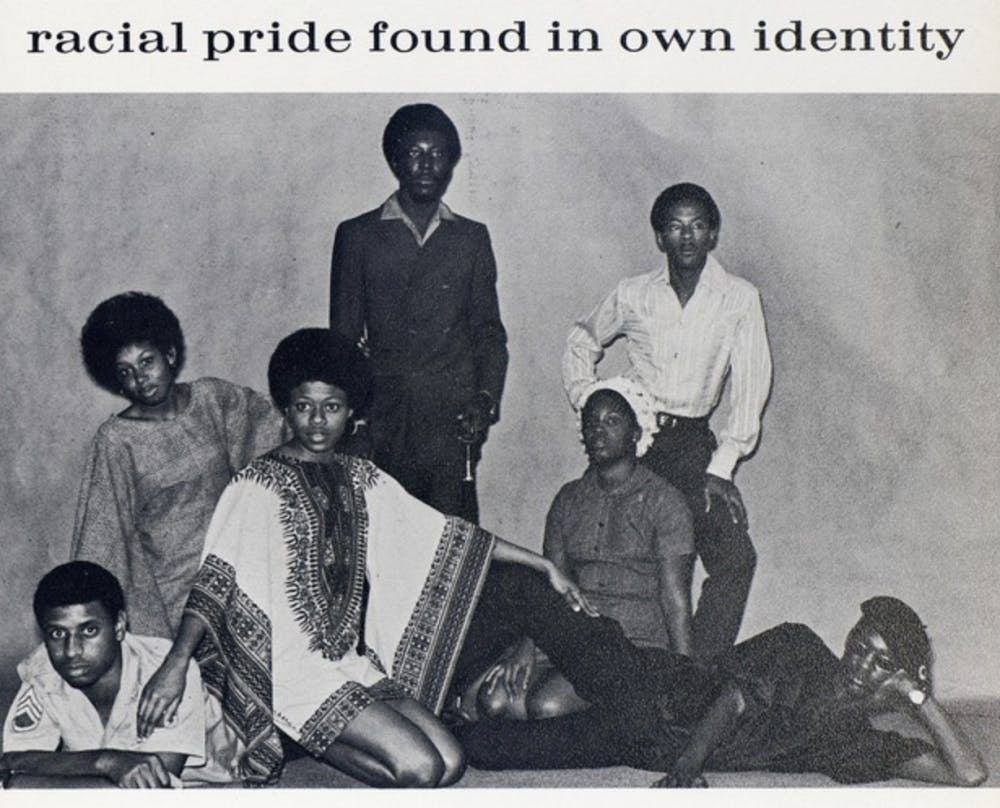

A page in the 1970 UF yearbook dedicated to black students.

“It was a really difficult month to get through. We were just talking among one another, pretty much giving ourselves an outlet to relieve our stress and express how upset we were with the things going on,” Walker said.

Walker planned to join a fraternity his freshman year during Spring 2014 but decided not to when two fraternity brothers posted photos of themselves wearing blackface in 2012. Austin said this incident sparked anger and motivated administration to support the major in a way it may not have before.

“People just get sick and tired of the foolishness that continues to happen over and over again,” Austin said.

The program expanded from offering only a certificate from the 1970s through the 1990s to creating a minor in 2006 and major in 2012.

Vincent Adejumo, a UF African American studies lecturer, said UF has the most students majoring in African American studies in the country. According to the university, other programs and departments have an average of 20 students in the major. Adejumo said UF’s program has 81 students.

“That tells you that there is a thirst for this knowledge, and the faculty and staff at the ground level have been doing the work necessary. The only way we’re going to take it to the next level is department status,” Adejumo said.

Sharon Burney, the African American Studies program assistant, said since 2003, she has worked under at least five directors. Many of the program’s professors belong to other departments, which limits the time they can allot to African American Studies. The program’s only full-time employees are three professors, one director and one staff member — herself.

“How you treat the most disenfranchised among you is a reflection of who you are at the core,” Burney said. “This is a program that has shown it’s been worthy through what we’ve been able to do with minimal staff and faculty. It should be celebrated, but it should also be invested in.”

In comparison, the University of Michigan’s Department of Afroamerican and African Studies has 57 full-time employees, program manager Elizabeth James wrote in an email.

“Every university needs that type of cross-cultural work because every place of the world is important,” James said.

UF’s program offers a black-oriented curriculum in a predominantly white institution.

Jireh Davis realized people treated her differently when she started elementary school. The one place she has not felt this is the African American Studies program.

Davis grew up in a predominantly white area of Arlington, Texas. Her friends growing up told her that their parents liked her because she was different from the stereotype of black people they believed to be true.

The 22-year-old UF political science and African American studies senior is now at UF, where 57 percent of the Student Body is white while about 7 percent is black. She said she is often the only black woman in her political science classes.

Davis did not have the confidence to talk about her race when she was a kid. She did not know how to respond when kids at her school thought the words “black” and “ghetto” were synonymous.

The program has provided a space where she feels included and has learned to use her voice to combat intolerance she faces while learning about the students who fought to be represented.

“It brings comfort, it brings a sense of home, a sense of relief, a sense of safety,” she said.

Contact April Rubin at arubin@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @AprilMRubin.

Black UF students pose for a photo in the 1970 university yearbook. The UF African American Studies program was founded in 1969.