Hilaria Cruz couldn’t read books in her language growing up.

Nothing had been written in her native tongue, so she decided to change that.

Cruz, a University of Louisville linguistics and Native American religion professor, presented “Developing Readers and Writers in Indigenous Languages: A Chatino Perspective,” a discussion about her experience developing an alphabet for the indigenous Chatino language, to about 40 people on Monday in the Reitz Union.

“Languages and the way in which they are very particular give us a window into humans and the human creative capacity,” Cruz said.

Growing up in an indigenous community in Oaxaca, Mexico, Cruz spoke Chatino, a Mesoamerican language spoken by the Chatino people, but learned to read and write in Spanish.

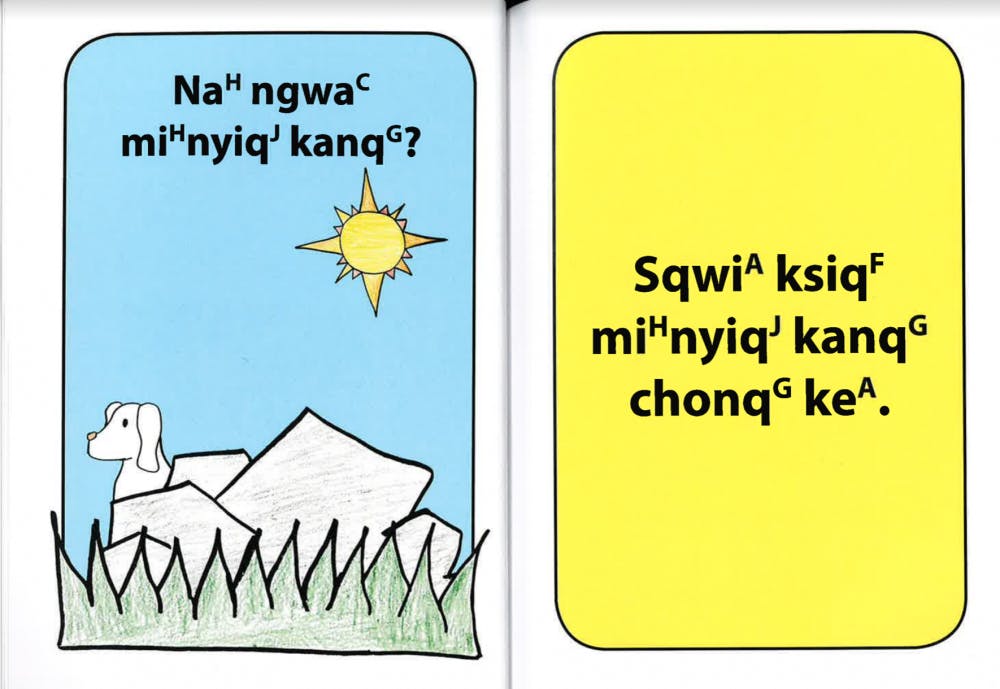

Inspired by the lack of books in her native language and her inability to read children’s books to her kids, Cruz and her sister worked to develop a Chatino alaphabet with linguists and anthropologists at The University of Texas at Austin. Dartmouth College students used the language to write eight children’s books.

The books were published in indigenous languages including Chatino, which uses the Roman alphabet and has 12 tones. The 150 books printed will be given to Chatino families for free.

Due to Mexican policies encouraging Spanish education and the high emigration of Chatino youth, the language has been lost over the years, Cruz said.

“It is very important for people to learn about different languages,” Cruz said. “Each language is a storage of wonderful information.”

UNESCO, which promotes international peace through education, science and culture, declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages. Cruz thinks it’s a great time for students to learn about world indigenous languages.

Cruz’s presentation helped Olivia Lafuente, an 18-year-old UF anthropology freshman, learn more about how language influences humanity and its importance with the next generation.

“If there is a certain aspect of culture that you want to study, all the factors tie into each other,” Lafuente said.

It is vital to document native tongues, as content could potentially be lost in translation, said George Broadwell, a UF linguistic anthropology professor, who helped Cruz develop the Chatino dictionary.

Broadwell hopes to create a course at UF about multilingualism, and Cruz hopes to create videos to teach the Chatino alphabet and support reading.

“People all over the world have knowledge of their history, environment and culture,” Broadwell said. “A lot of that knowledge comes from the language they speak.”

Contact April Rubin at arubin@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @AprilMRubin.

Hilaria Cruz and her sister worked to develop a Chatino alaphabet with linguists and anthropologists at The University of Texas at Austin. Dartmouth College students used the language to write eight children’s books. Courtesy to The Alligator