Rachel Kalfin was just trying to go to her fashion design class.

The now-27-year-old former inmate looked forward to her classes at the prison.

They served as an outlet for her to better herself and stay out of trouble.

But one morning, there was more than a gate that stood in her way.

As she approached the gate for her class, it slammed and locked in front of her.

A guard stepped in front of the doorway, his medium build blocking her path, which was just wide enough to fit one person.

The guard said she could earn her way through the gate if she performed oral sex on him.

Kalfin denied, but when she turned to find someone else to open the gate for her, the officer handcuffed her for being disrespectul.

When she reported the harassment and explained the situation to staff members, Kalfin said they agreed that she was being disrespectful. The report landed her in confinement, she said.

“They told me it was all my fault,” she said.

It was reports like Kalfin’s that prompted the Department of Justice to launch a federal investigation in August to look into allegations of sexual abuse and harassment at Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala. The investigation is ongoing and could take months, said Laura Cowall, an attorney with the Civil Rights Division of the department. If proof of the allegations is found, the findings will be made public.

Patrick Manderfield, the press secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections, wrote in an email that the investigation is welcome and that the department is committed to assisting the department with the inquiry.

“The Department does not tolerate any form of abuse,” Manderfield said. “We take all allegations of this type of behavior very seriously.”

The women’s prison currently houses 2,367 inmates. Since 2015, Lowell has taken significant steps to increase inmate security, Manderfield said.

The Office of Institutions has added additional security cameras in housing units and audio recording to help identify and respond to misconduct, he said. The prison has also increased the storage capacity of video cameras to prevent overwriting.

Lowell is also subject to an independent audit by the Department of Justice to make sure it’s complying with the Prison Rape Elimination Act, which is designed to investigate and eradicate prison rape, Manderfield said.

The most recent report occurred in 2016, according to the Florida Department of Corrections website. During the audit cycle, there were 158 allegations of sexual abuse and harassment at the prison. Of these, 86 were allegations of abuse and 29 were harassment by staff. The report does not indicate whether the allegations were founded.

Kalfin spent 30 months at Lowell for burglary and grand theft, during which she said it was common to see or hear about girls performing sexual favors for guards for a roll of toilet paper or other products in short supply.

“A lot of girls are asked sexual favors, and a lot do them because it’s their only attempt at survival,” Kalfin said.

Kalfin’s report of sexual harassment landed her in a 4-by-8 foot room for 60 days. While in confinement, she was served “Tuscan Stew,” a cold mixture of leftover food including rice, beans or noodles from the week before. Twice a week, she got to shower for two minutes, and if she was lucky, she got menstrual pads, Kalfin said.

At any moment, she could have a seizure that would knock her to the floor, and the guard who was supposed to check on her every 30 minutes was often asleep, or worse, apathetic, she said.

Kalfin had six seizures in confinement that left her lying on the ground unconscious and waiting for medical help, Kalfin said.

By the time it was over, Kalfin was 35 pounds lighter, she said.

Kalfin was released in August 2017 and is now engaged and expecting a son, but the effects of the trauma she experienced at Lowell linger, she said.

“It’s been really hard for me to be close with anyone, emotionally and physically,” she said. “When my fiancé moves, I jump and freak out because I’m scared. It’s not of him. It’s because of what they did in there.”

A few minutes from Kalfin’s home in West Palm Beach, Debra Bennett gets ready to go to work.

After being released from Lowell in March, Bennett started working two full-time jobs: one at a call center and another at a fast food restaurant.

Sometimes, kids stop and stare at her arm, which juts out at an odd angle.

While waxing a floor in Lowell, Bennett slipped and fell, fracturing her right arm. While she received care from nurses at the prison, her arm was fixed crookedly, Bennett said. She wasn’t given physical therapy for her injury and now can’t move her fingers.

“I’m tired of having a right arm that doesn’t really work,” Bennett, 50, said. “I’m tired of dropping stuff all day long and of the numbness and the pain.”

Since the investigation is focused on sexual abuse and harassment at the prison, Bennett fears that the investigation will not uncover the physical abuse that takes place too, she said.

Bennett spent about 16 years in the Florida prison system on charges such as drug trafficking and violating probation and said she has been to every compound in Florida. Lowell was the worst of them all, Bennett said.

She hopes the federal investigation will draw attention to the problems there and cover all types of abuses, instead of just sexual, but she knows the women are scared to talk to investigators out of fear of retaliation, she said.

While Bennett believes there are people who deserve to be sent to prison for their crimes, she said that people never deserve to be treated like the women were in Lowell.

“Your punishment is you’re removed from society,” she said. “It doesn’t mean that you are supposed to be abused in the way that Lowell Correctional abuses you.”

Contact Jessica Curbelo at jcurbelo@alligator.org and follow her on Twitter at @jesscurbelo

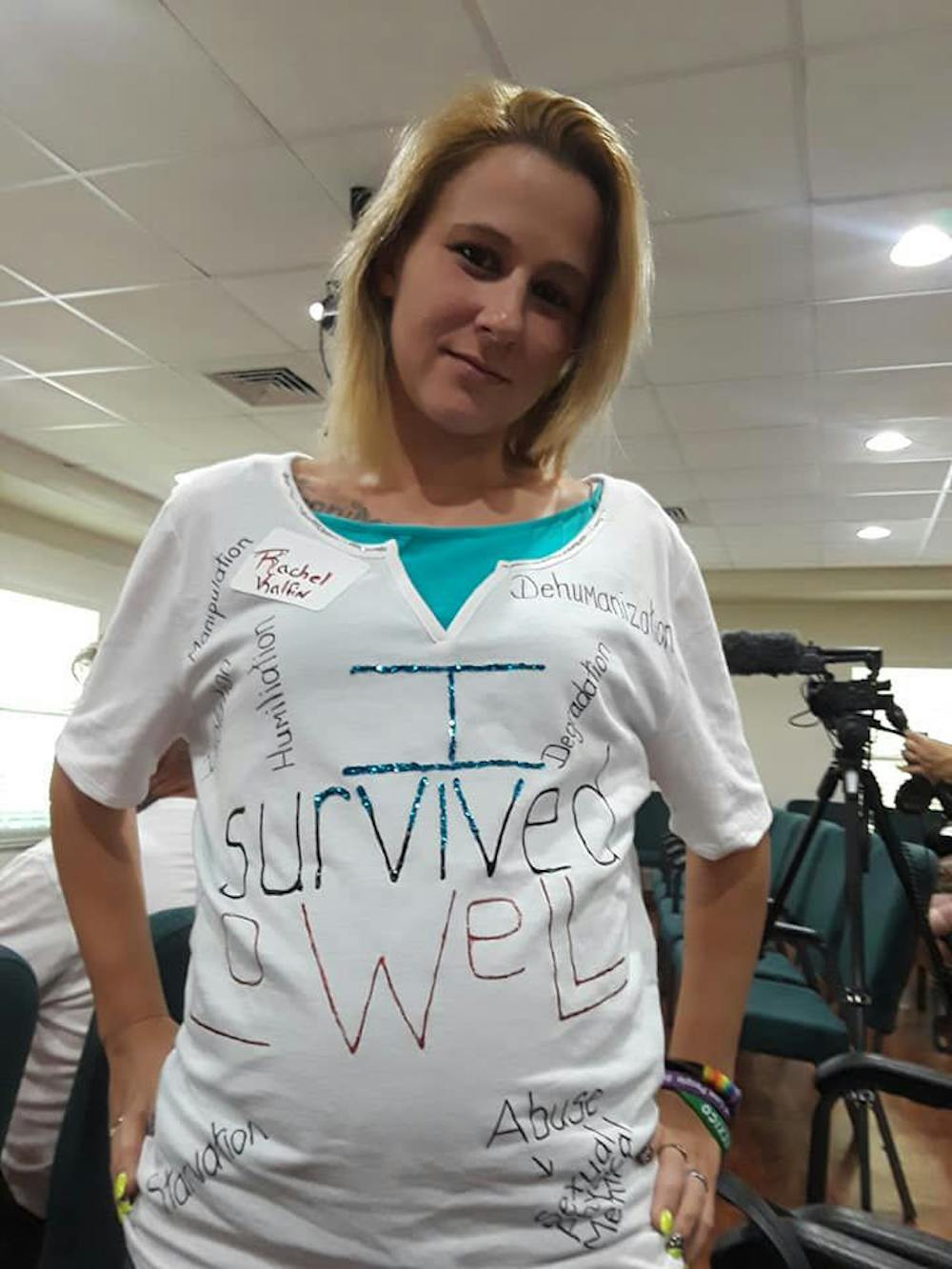

Rachel Kalfin, a former inmate at Lowell Correctional Institution, poses in her “I survived Lowell” shirt. On August 19, she attended a meeting in Ocala with other former inmates to talk to the Department of Justice team about abuses they experienced.