Editor's note: This story was corrected to reflect Stansly was not in the Peace Corp. A change was also made to reflect he earned his nickname “psyllid slayer" two years ago while working to combat citrus greening in Florida.

The weevil was the best thing that happened to Philip Stansly.

“Dad always said that, ‘If it wasn’t for weevil, none of y’all would be here today,’” said his son Ted Stansly.

His dad was full of snappy sayings and quotes, Ted Stansly said with a small sigh.

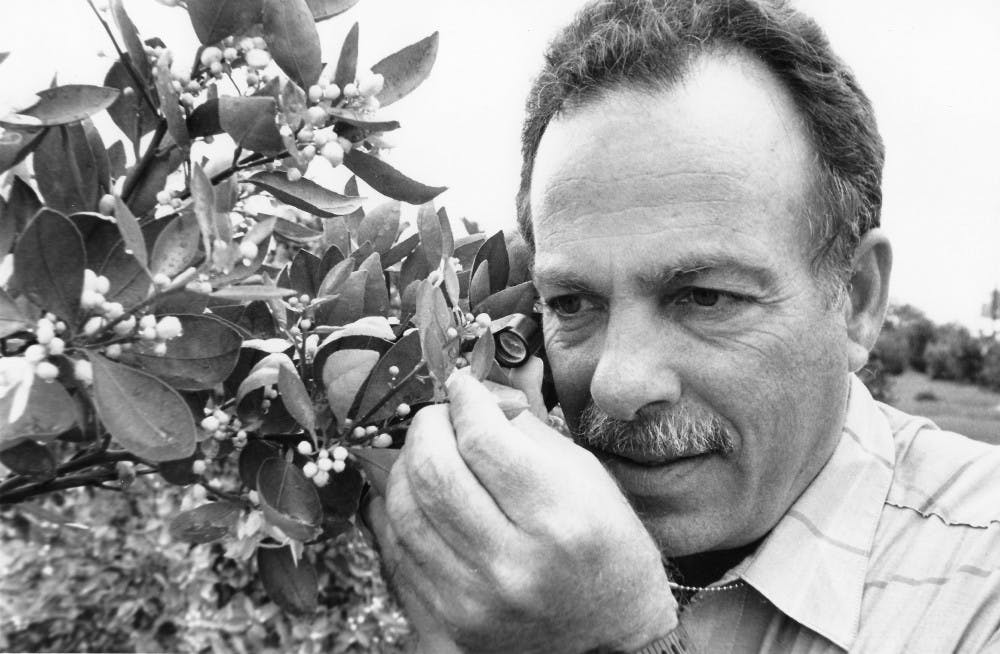

Philip Stansly, a UF professor and international entomologist, died at 74 years old on Sept. 12 in Fort Myers after more than a year-long battle with colon cancer.

Stansly’s career began in Africa. He would leave his lodging each morning on camelback to release swarms of ladybugs. His efforts helped keep insects from killing off the date palms locals depended on for food, shelter and fuel, he said.

The self-proclaimed “bug doctor’s” travels led him from the Sahara Desert to Mexico to Venezuela and Ecuador in pursuit of fighting small plant-eating pests.

Stansly ventured to a research facility in Lazaro Cardenas, Mexico more than 30 years ago in search of a solution to the boll weevil, a pest wreaking havoc on all kinds of crops. This trip cemented his legacy, his son said.

Ted Stansly, Stansly’s oldest of two sons and a 35-year-old UF doctoral agronomy senior, said this trip to southern Mexico is where Stansly met his wife, Silvia Stansly. She survives him along with his two sons, two daughters, one sister, granddaughter and niece.

The extroverted scientist was happy to share knowledge with anyone, said Blair Siegfried, the UF entomology department chair.

“We’ve all become so specialized that Phil was one of those rare individuals who knew a lot about a lot of different subjects,” he said.

Stansly worked with the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at Southwest Florida Research and Education Center in Immokalee, Florida since 1989.

Kelly Morgan, the Southwest Florida Research and Education Center director, said he worked with Stansly at the center for 13 years. Together they studied how to improve tree health and overcome impacts of fertilizers.

“He wasn’t into science just for the science. It had to improve the production practices and benefit the grower,” Morgan said. “It really is (his legacy).”

He was always there to provide solutions to these crises, Siegfried said.

“Phil was one the of the best entomologists I’ve ever known,” Siegfried said. “I think he saved growers in very difficult situations when there were certain pest outbreaks.”

Stansly was committed to international agriculture and taught students in his lab who went on to have successful careers in the agriculture industry, Siegfried said.

While working to combat citrus greening in Florida two years ago, Stansly earned the nickname “psyllid slayer.”

He plans to work with IFAS to create a scholarship fund for international students to honor and continue Stansly’s decades of work put into his program, Stansly said.

Stansly spoke at his last Citrus Expo less than one month before his death while battling the painful effects of cancer, Siegfried said. Though most experts gave one presentation, he gave two.

“If you listen to his words, near the end you can almost hear he was saying his goodbyes, and I felt like that was pretty noble of him,” Ted Stansly said.

Contact Angela DiMichele at adimichele@alligator.org and follow her on Twitter at @angdimi