Sydney Look was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was 16 years old. The condition causes her pancreas to produce little to no insulin, depriving her of the hormone that regulates her blood glucose levels.

“Diabetes is a 24/7 disease,” Look, 23, said. “I often wake up in the middle of the night to a high or a low, and that affects my sleep hygiene and how I do in school the next day.”

The medical student shared how the disease and its costs affect her life at the town hall on the high cost of insulin prescriptions at the Reitz Union on Tuesday night. The meeting was organized by Right Care Alliance of Gainesville, which Look is a member of, and UF’s Department of Pediatric Endocrinology.

More than 20 people attended the meeting, which featured three presentations, including Look’s, followed by a Q&A session.

The increasing cost of insulin was the main topic of discussion. Between 2002 and 2013, the average price of insulin in the U.S. tripled from $40 to $130 per vial. A vial typically lasts a patient a week or two, according to one of the presenters at the town hall.

The extreme jump in price makes insulin the sixth most expensive liquid on Earth at $26,000 per liter, and by 2020, the industry will be worth more than $48 billion worldwide.

“There’s only three manufacturers, and they kinda carved out the global market,” said Dr. Mark Atkinson, director of UF’s Diabetes Institute. “Competition decreases prices, but there’s a monopoly here.”

Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi dominate the insulin industry. Atkinson said the cost to make the actual glass vial is only about 30 cents, and analog insulin, which is synthetically made and acts rapidly, costs no more than $10 to produce.

“There’s been research over the last few decades that the cost to manufacture it has been relatively stable, but the cost that they charge has been increasing dramatically,” Atkinson said.

Type 1 diabetics like Look must take insulin to survive with no alternative medicine. About a third of people with Type 2 diabetes have to take insulin, too.

A study from Emory University found that 17 percent of patients admitted for diabetic ketoacidosis – a potentially deadly complication of diabetes – had stopped using insulin because they couldn’t afford it.

One in four diabetic patients at a clinic in Connecticut admitted to cutting back on their insulin due to the cost, according to a Yale University study.

“I don’t want to have to lie to my doctor about how much insulin I use in order to hoard extra,” Look said.

Look originally took insulin injections after her diagnosis, but after six months, she switched to an insulin pump. The pump costs her about $6 every three days.

She also uses a continuous glucose monitor, which relies on a sensor wire inside her. The device has a transmitter that sends the information via Bluetooth to another device Look uses to track her levels. The glucose monitor costs her about $50 per week.

UF’s student health insurance has cut the price in half for her from $800 to $400 per month from her old insurance. Look said without her father’s help, she wouldn’t be able to afford all the technology that makes her life as a diabetic easier.

“The continuous glucose monitor has been life changing for me. Unfortunately, it’s really not widely available because of its price,” Look said. “A lot of people don’t have access to these things.”

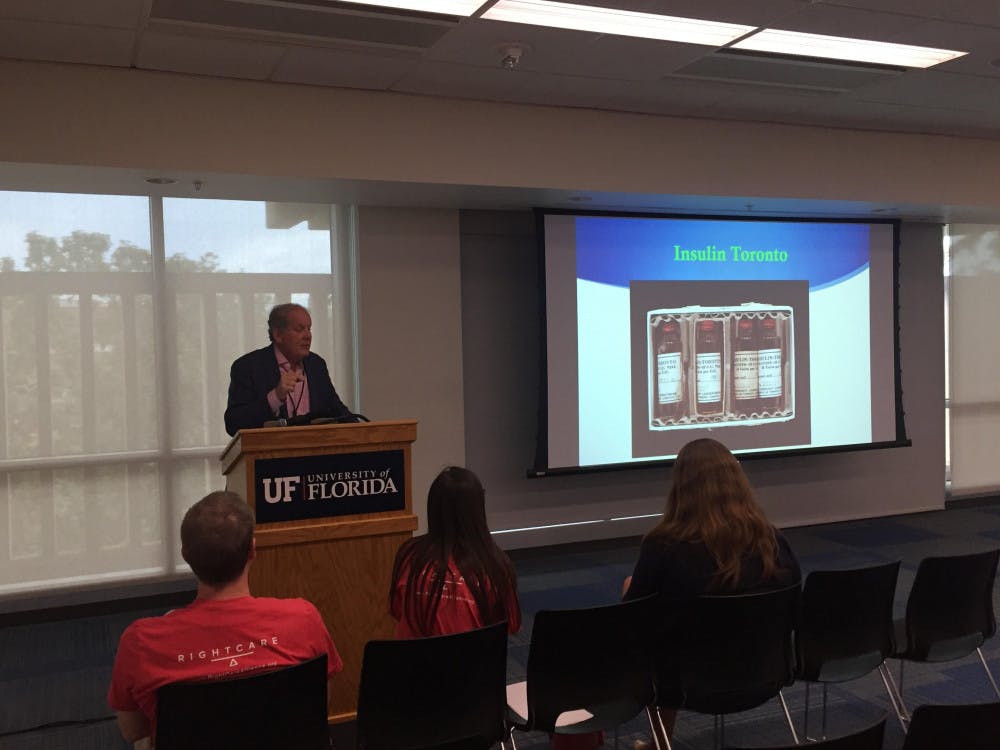

Dr. Mark Atkinson presents a PowerPoint at Tuesday's forum in the Reitz Union.