McKethan Stadium is quiet now.

Florida just wrapped up a road trip to Lexington, Kentucky, this weekend, where the No. 1 Gators took two of three games from the Wildcats. Their first contest back home will be against Mercer on Tuesday night at 6, but if you were to walk by the stadium sometime Monday afternoon, you’d probably never know.

You might hear the rhythmic whir of a lawnmower or the persistent ping of leather meeting aluminum, but the stadium seems dormant in the absence of fans and teams and life. Rest assured that inside, where nobody’s watching, plenty of preparation is going into Tuesday’s game against the Bears.

Mitchell Wydetic knows that better than anyone. He’s the head student manager for Florida's baseball team, and his job is basically to make sure everything that needs to get done behind the scenes does indeed get done. His journey started back at Henry Plant High School in Tampa.

He wanted to play baseball, but he was too small. At 5-foot-8 and without standout skills, his coach approached him with a proposition: What if he gave up playing and used his strongest baseball attribute — his brain — to help coach the team?

“People don’t give up their career at 15 to start coaching,” Wydetic thought. “They do that at 35.”

But he wanted to stay around baseball, and becoming a student-coach would make that happen.

“I’ll do it,” he finally decided, “but if I don’t like it after two weeks, I’m out.”

About six years and one college enrollment later, he’s still performing many of the same tasks minus the actual coaching. And on a recent Tuesday, he sat down to explain how he and the rest of the operations staff makes sure games get played smoothly.

The Balls

What would baseball be without, well, baseballs? You can’t play a game without them, after all. But the scale at which UF purchases these spheres of cork and yarn wrapped like sausage between two leather strips may surprise you.

Wydetic explained that UF orders about 35 cases of baseballs every fall. Each case carries 120 balls, which makes the total about 4,200. Each ball is worth about $5 individually, Wydetic said, without factoring in any bought-in-bulk discounts.

Some of them get used right away as practice balls, which are kept in their own basket for batting practice. Others are saved for games.

These game balls are rubbed in a special mud called Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud that comes from a secret spot along a river in New Jersey. The mud is commonly used in professional and advanced amateur baseball, and one professional-sized buckets costs $100.

“We rub up each baseball,” Wydetic said, “just to take the shine off.”

This gives pitchers a better grip and batters some peace of mind knowing that a 95-mph fastball is less likely to slip and shatter their teeth. So what happens to mudded-up game balls on a pitch in the dirt or a foul tip?

You may have noticed that when something alters the feel of a baseball, catchers or pitchers will toss them aside in favor of a new game ball. The ones that are scuffed get put into the practice basket until they become dented, shredded or maimed beyond use.

They save some of the really scuffed ones for rainy days — literally — opting to use them when the field is wet and they don’t want to damage any more pristine baseballs. But once they reach that beyond-use point, they’re destroyed, thus ending the life cycle of a college baseball.

The Uniforms

Wydetic and the other student managers store Florida’s uniforms in numerical order on racks in the team’s equipment room. You can find six kinds of jerseys — white, blue, orange, black, grey and pinstripes — and five kinds of pants — long white, short white, long grey, short grey and long pinstripes — cramped into this soap-scented oasis.

The managers lay out the uniforms before games and launder them after. Players aren’t allowed to depart with their jerseys or pants. Which uniform is worn depends on the day and the location.

Baseball teams have traditionally worn white/light-colored uniforms at home and grey/dark-colored uniforms on the road. Florida tries to keep to that tradition.

That’s why Friday usually means white, Saturday is usually pinstripes and Sunday is sometimes the more spirited blue or orange, much like what the Miami Marlins used to do before their orange jerseys were retired.

The starting pitcher also has some say.

“For example,” Wydetic said, “Brady Singer loves to wear white.”

As for pants, Wydetic said players rarely wear the shorts anymore. Last year, the team had stirrups socks, so sometimes they’d wear the shorts with them. This year, the team’s socks are always solid blue, so there’s really no need. Plus, given his height, he doesn’t find them flattering.

“If you’re shorter,” he said, “you kinda look like a hobbit.”

The Gloves

It starts with a catalog.

Easton, which has a contract with UF, sends it to Florida each fall. It boasts all the new features and options for gloves available to players. That means models, pocket types, stitching colors — basically everything you could ever want in a glove is made possible.

The catalog is passed along to players, who build their own gloves each season. And if you’re a two-way player like catcher/first baseman JJ Schwarz or pitcher/outfielder Austin Langworthy, it means you build two gloves.

“A lot of the people think it’s really cool,” Wydetic said, “because for most of their lives, picking a glove has been all about, ‘Is this the right size for me?’”

Some players take advantage of the options. Former outfielder Buddy Reed, who’s now a member of the San Diego Padres organization, requested a glove made of light blue leather and orange stitching.

“He liked it so much that he hardly ever used it,” Wydetic said.

Some others take advantage in a different way. Closer Michael Byrne, for example, had “Hands” embroidered onto his infielder glove because, Wydetic explained, he loves taking ground balls on off days and thinks he has quick hands.

Players can also get their names, Bible verses or almost anything else tattooed onto their customized leather.

“Anything that’s not profane or can’t be seen on TV,” Wydetic said, “they can put that on a glove.”

The Chalk

One of Wydetic’s final tasks to ensure each game runs smoothly is to draw the batter’s box using a tub of chalk on wheels. He sweats each time, he explained, and not because it’s a physically demanding task.

He remembers having to draw the box before a Super Regional game last season. The game was going to be televised on ESPN.

“If this doesn’t come out right,” he thought, “everyone watching on television is gonna think we’re idiots.”

Luckily for him, the team has a process to try and ensure there are no slip-ups. It starts with a stencil.

The stencil is basically a big rectangle that’s placed next to home plate. A spotter observes the placement from between home plate and the mound to make sure it’s perfectly parallel with the sides of home plate. Then the chalk is dropped.

This process has allowed Wydetic to escape any mistakes so far, whether on ESPN or otherwise. As for what would happen if a line was out of place, his explanation mirrors the solution for any problem in his line of work.

“If something goes wrong, you have to figure out how to fix it,” he said. “Quick.”

Follow Ethan Bauer on Twitter @ebaueri and contact him at ebauer@alligator.org.

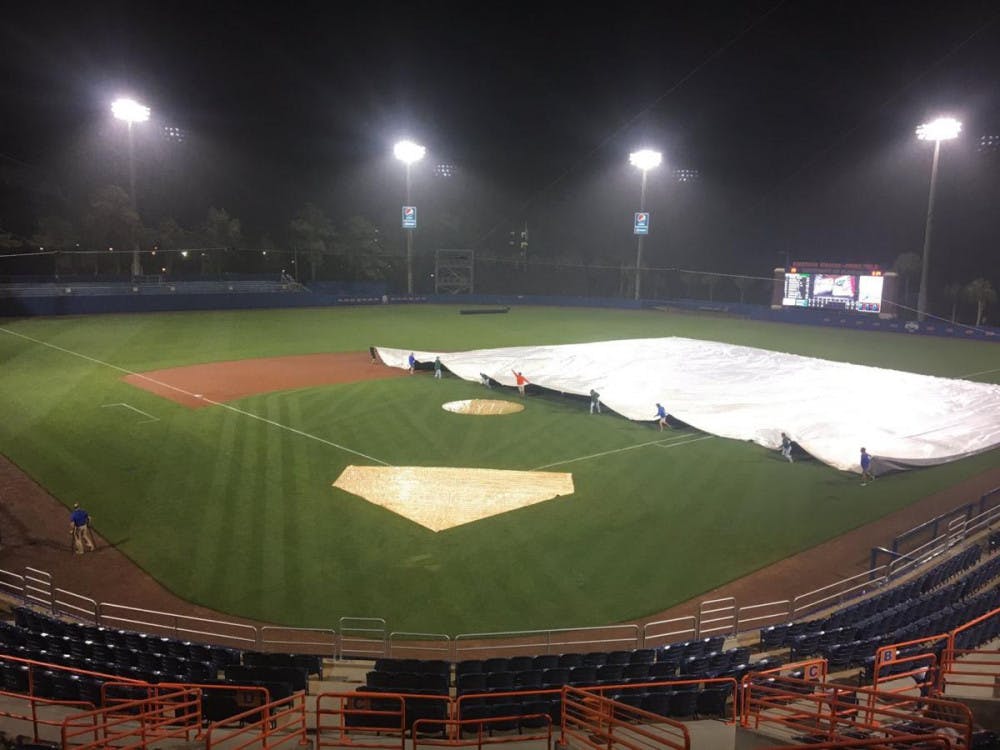

The grounds crew at McKethan Stadium pulls a tarp over the field during a rain delay on April 4, 2017.