THE RESOURCES

A single mother of five and Circle K cashier, Cara Chatmon had just moved her family from East to West Gainesville in 2014.

She wanted to move her kids into a better neighborhood. She didn’t think her fifth-grade daughter Tamia’s adjustment from her old eastside school, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Elementary School, would be difficult.

But about two months after her daughter started the new school, Chatmon received a call. Ms. Smith wanted to discuss Tamia’s progress.

Smith showed Chatmon the class gradebook, pointing to Tamia’s name: low Cs, borderline Ds. The class average was a B+.

“What’s the situation like at home?” Smith prodded.

Chatmon felt broken. She thought she’d made a big deal out of her children’s education. She didn’t want them to follow in her own footsteps of working low-wage jobs and needing government assistance.

“At first I was hurt, like did I do something wrong?” Chatmon said.

What about the trips to the library every Saturday morning for homework and reading, she thought. What about the books her daughter checked out?

When Chatmon said home was fine, Smith asked where Tamia had transferred from.

“Rawlings,” Chatmon said.

The Stephen Foster teacher paused. Then she gave a thoughtful nod.

“That could be the reason,” she said. “Rawlings doesn’t have the resources.”

“NIGHT AND DAY”

Alachua County’s elementary schools are divided between east and west, and black and white.

While in eastside elementary schools, most students are black and fail Florida’s statewide end-of-year exams, westside elementary school students are typically white and pass the exams. Although nobody can point to a single reason the achievement gap exists, people mention cyclical poverty, racial segregation within the city, lack of parental resources and the current zoning map.

Even inside westside schools where the majority of students pass the Florida Standards Assessments, or FSAs, black student performance lags significantly behind that of their white counterparts.

Out of all 67 Florida counties, Alachua County has the largest achievement gap between white and black students on final exams, according to Alligator archives.

Four schools west of Interstate 75 — Meadowbrook, Hidden Oaks, Lawton Chiles and Kimball Wiles Elementary Schools — are all majority white and were graded as ‘A’ schools in 2017.

About 70.7 percent of these four schools’ students between 2013 and 2017 passed their language arts FSA exam.

In East Gainesville, in three of four elementary schools, about eight in every 10 students are black.

Only about 22.9 percent of students in these schools — Rawlings, Metcalfe and Lake Forest Elementary Schools — from 2013 to 2017 passed their FSA language arts exam.

Chanae Baker sees the divide first-hand.

Twice a week, Baker volunteers at Meadowbrook, where her 8-year-old goddaughter, Jyla, attends second grade.

Between the smart boards and the building’s mix of brick and bright white-painted walls, she said she’s in awe of the resources.

Then, once a month, she volunteers at Rawlings, where the 50-year-old building’s classrooms are gloomy and the textbooks are old and worn.

The difference extends to non-physical resources, she said. While Meadowbrook has a strong PTA, many Rawlings parents struggle to get involved because they work multiple low-wage jobs.

“It’s like night and day,” she said.

***

Above the whiteboard in Lilliemarie Gore’s fourth-grade math and science class, in an Idylwild Elementary School portable, a message hangs in orange and blue letters.

Nothing is greater than learning, the plastic letters read.

Since graduating from UF in 2005 with a master’s degree in education, Gore has committed her time to teaching in the eastern part of the city. It’s where help is needed.

After working for five years at Williams Elementary School, an eastside school, she moved to Idylwild, a majority black school in the west.

In both schools, she’s witnessed the underperformance of her black students.

“Personally, I believe it’s getting worse,” she said.

The achievement gap between white and black students is severe at Williams, Gore said.

Williams has a magnet program that is majority white, while the non-magnet program is mostly black.

While nearly 94 percent of Williams’ white students passed their language arts FSA in 2016-17 academic year, only about 25 percent of its black students passed.

The same trend exists for black students in West Gainesville schools, even those without magnet programs.

Even though Tamia passed her fifth-grade language arts FSA at westside Stephen Foster, nearly 86 percent of black classmates failed.

Only 8.7 percent of her white classmates failed.

DIVISION

Eileen Roy, the school board’s longest-serving member from District 2, thinks the current zoning map is a major cause of the divide.

In December 2003, the board redrew the map to a neighborhood style, which prioritized walking distance from homes rather than factors like having a mix of races within the same schools. As a result, she said the schools became much more segregated by race and economics.

Roy wasn’t on the board at the time, but was a member of the Zoning Task Force in 2002, which advised against the model, she said.

“A number of us said if we rezoned schools, we’ve got to have diversity as the No.1 criteria,” she said.

District 4 School Board member Leanetta McNealy said rezoning — or what she calls “the R word” because she sees it as a taboo term that people don’t talk about enough — would help close the achievement gap.

Chris Busey, a UF professor of education, said he’s not sure redrawing the map would end segregation. White parents would move their children to private schools or charter schools.

“What’s happened in the past when we’ve rezoned schools is that there’s been white flight,” he said.

When Elizabeth “Buffy” Bondy, a UF professor of education, thinks about how to fix the achievement gap, she turns to literature Nobel Prize Winner William Faulkner.

“‘The past is never dead, it’s not even passed,’” Bondy quoted.

Bondy said the conditions students are born into and the privileges they may or may not have come together to influence their education.

“The reason for the gap is broader than what’s happening in an individual classroom,” she said.

BREAKING POINT

As East Gainesville schools struggle with underperformance and racial inequity, West Gainesville schools face overcapacity.

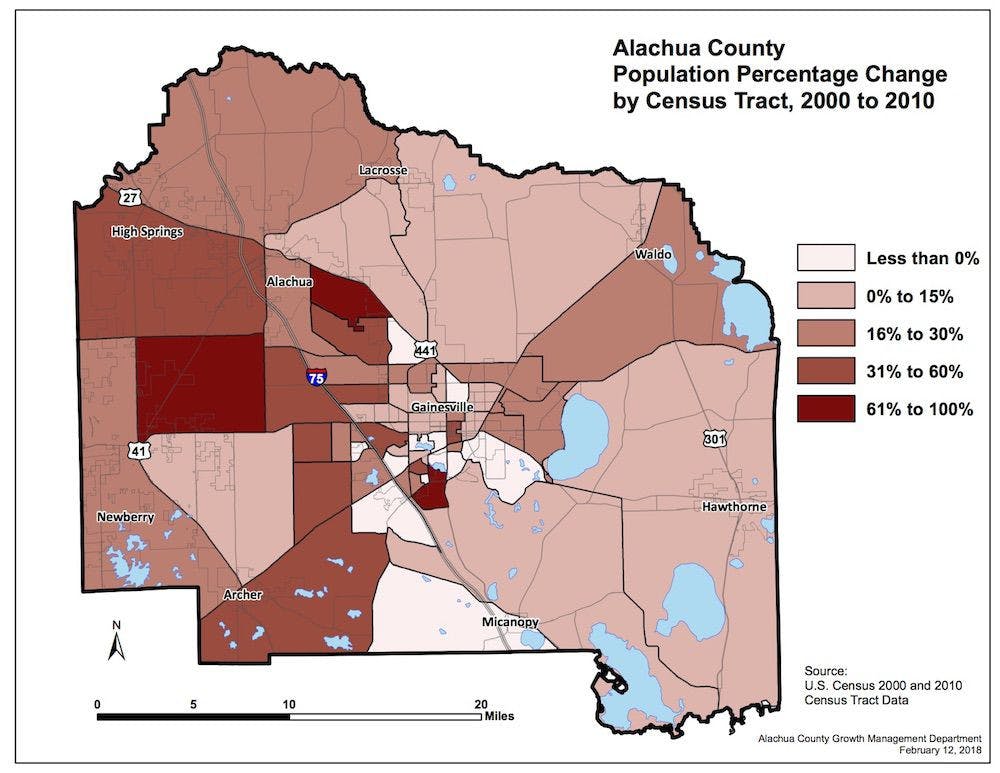

West Gainesville grew 13 times more than East Gainesville between 2000 and 2010, according to census data. At least nine schools in the West are at more than 100 percent capacity.

School board members hope to mitigate overcrowding with a new school in the west.

Although the project does not have a timeline for construction, the state approved it and the district is discussing a location, McNealy said.

“It’s needed,” McNealy said. “We’re considered a portable city. When you go to certain school sites, we have so many portables on the west side.”

At Wiles Elementary School, a school built for 700 that now has 940 students, the first lunch bell rings at 9:45 a.m.

The early-start lunch is the only way to cycle students to the cafeteria, said Wiles Principal Barbara Buys.

In her 18 years as the school’s principal, Buys has never had this many students.

A map of population changes in Alachua County. Courtesy to The Alligator.

While more portables can always be added, she said the rest of the school’s resources are more strained.

“We might be getting toward a breaking point soon,” she said.

Graham Maxey shook his head as he walked up to Littlewood Elementary’s front entrance to pick up his two granddaughters, 7-year-old Jade and 5-year-old Jordan.

Every day the car line stretches far down the streets. Last year, Littlewood was about 122 percent over capacity.

“I know they’re doing the best they can, but it’s a problem,” he said. “This school’s too overcrowded.”

NEXT STEPS

For five years in a row, Lake Forest Elementary School, on the eastside, was an F school.

Last year, it jumped to a C.

For Karla Hutchinson, who started as principal last year, the spike in performance all came down to establishing a culture of high expectations.

Between January and April 2017, Hutchinson and a group of administrators had a one-on-one meeting with each of Lake Forest’s 347 students. It was important to make each student aware of their performance — good or bad — and set concrete goals, she said.

Get better grades on homework. Make a study plan. Stick to it.

“It was really eye-opening for a number of our students,” Hutchinson said. “We didn’t focus on the past, we were focused on the present and on the future.”

Alachua County Public Schools spokesperson Jackie Johnson said the district is aware of the achievement gap and has long made it a top priority.

In 2016-2017, while westside schools received more overall funding, the district allocated more funding per student to eastside schools, Johnson said. The money went toward more staff and teachers’ salaries for eastside schools.

The Alachua County Council of PTAs also surveyed both east and westside schools, and will devise a 10 to 20-year plan on renovation and remodeling plans for each school, Johnson said.

Johnson said they face problems with state funding cuts. In the last 10 years, the district has lost $168 million in facilities funding alone.

“We’ve been getting hit from all angles to be honest,” she said.

On the November ballot, voters will decide on a half-cent sales tax the district expects will amount to $20 million a year to fund school facilities. It would cost the average county household about $58 annually.

***

Gore sees herself in her students.

Growing up in Naranja, Florida, about 40 minutes southwest of Miami, Gore, 35, said she lived in poverty, much like her students.

But in third grade, Gore’s teacher, Ms. Jackson, showed her something she hadn’t yet known: she could get through life with education.

“She treated me as a whole, well-rounded child,” she said. “She made me believe in myself.”

Gore sees her task as simple: inspiring students to push past their challenges. She wants to be their Ms. Jackson.

“I just want to be that light to these students, to love them and care enough about them to change,” she said.

Gore sees her task as simple: inspiring students to push past their challenges. She wants to be their Ms. Jackson.

“I just want to be that light to these students, to love them and care enough about them to change,” she said.

Contact David Hoffman at dhoffman@alligator.org. Follow him on Twitter at @hoffdavid123.

[FILE PHOTO] 35-year-old Lilliemarie Gore leads students of Idylwild Elementary School through a series of math exercises. Mrs. Gore was awarded the title of "2017-2018 Alachua County Teacher of the Year" earlier this month.

![<p dir="ltr"><span>[FILE PHOTO] 35-year-old Lilliemarie Gore leads students of Idylwild Elementary School through a series of math exercises. Mrs. Gore was awarded the title of "2017-2018 Alachua County Teacher of the Year" earlier this month.</span></p><p><span> </span></p>](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/ufa/bc25e72c-c968-42c7-9f0e-41b4a1008d81.sized-1000x1000.jpg?w=1000)