Jamie (which is not the real name of the victim) woke up on the floor next to a couch she didn’t recognize. The party was a few hours old.

She would only be alert for a few minutes, and she would use those minutes to get to the safety of familiar surroundings. When a man approached to check on her, she asked him to take her home.

The next thing Jamie remembers is being in her own bed with her pants off and that man between her legs.

“Wait, what are you doing? Stop!” she remembers saying. She told him she didn’t want to have sex. He told her they already had. “And you liked it,” she recalls him adding, imitating that slithery smugness that too often accompanies accounts of sexual intimacy.

In my interviews for this investigation, this is the most consistent image of rape on UF’s campus: Girl gets drunk, girl blacks out, girl wakes up with a stranger in her bed, often in the act of raping her.

Google search “sexual assault blackout,” and you’ll find pages of teachers, scientists, law enforcement officials and lawyers trying to rub clear the blur in that image, debating the difference between intoxication and incapacitation. Can you consent while blacked out?

Sexual assault survivors themselves offer no clear answers: When I asked how men and women should navigate situations like Jamie’s, where one or both parties are operating on autopilot and “yes” may not actually mean yes, my dialogues unfailingly turned choppy.

“If you are pursuing another person who is visibly and obviously much less sober than you, you’re taking advantage of that person.,” Abby, another survivor I interviewed, told me.

“And you get that gray area if you’re both really, really intoxicated, but …,” she trailed off. “But that — you know, honestly, I’m not sure … it’s tough — it’s a tough thing to combat.”

The UF Student Conduct and Honor Code and Florida state laws feign greater certainty but couched in legal jargon is all the ambiguity of the sighs and pauses from interviews like Abby’s.

A Student Legal Services presentation on alcohol and consent reads that according to FL. Statute 794.011, an “inability to make decisions due to intoxication by any substance” does not qualify as consent. But what constitutes “inability?”

Take Abby, for example. She was set up last minute with a UF fraternity member — a friend of a friend — for her sorority formal. On the night of the event, his attitude and demeanor were immediately off-putting (he showed up late complaining with not-so-subtle pride about a hangover from last night’s drunken adventure at another formal). They both drank to escape the tension of a bad date, and both ended the night with mussed hair, wrinkled shirts and eyes glazed over in alcoholic stupor.

Abby went home with her date that night (in no capacity to refuse, by her own account), blacked out at his apartment and woke up underneath him, having sex.

With hesitant certainty, she told me she considers the experience rape. “It was just really violating,” she explained.

A close friend of Abby’s who attended the formal with her and picked her up the next morning, corroborated this account but mentioned that as far as she could tell, Abby’s date was as drunk as she was. If he was equally incapacitated, equally unable to consent, did he think he had been raped, too?

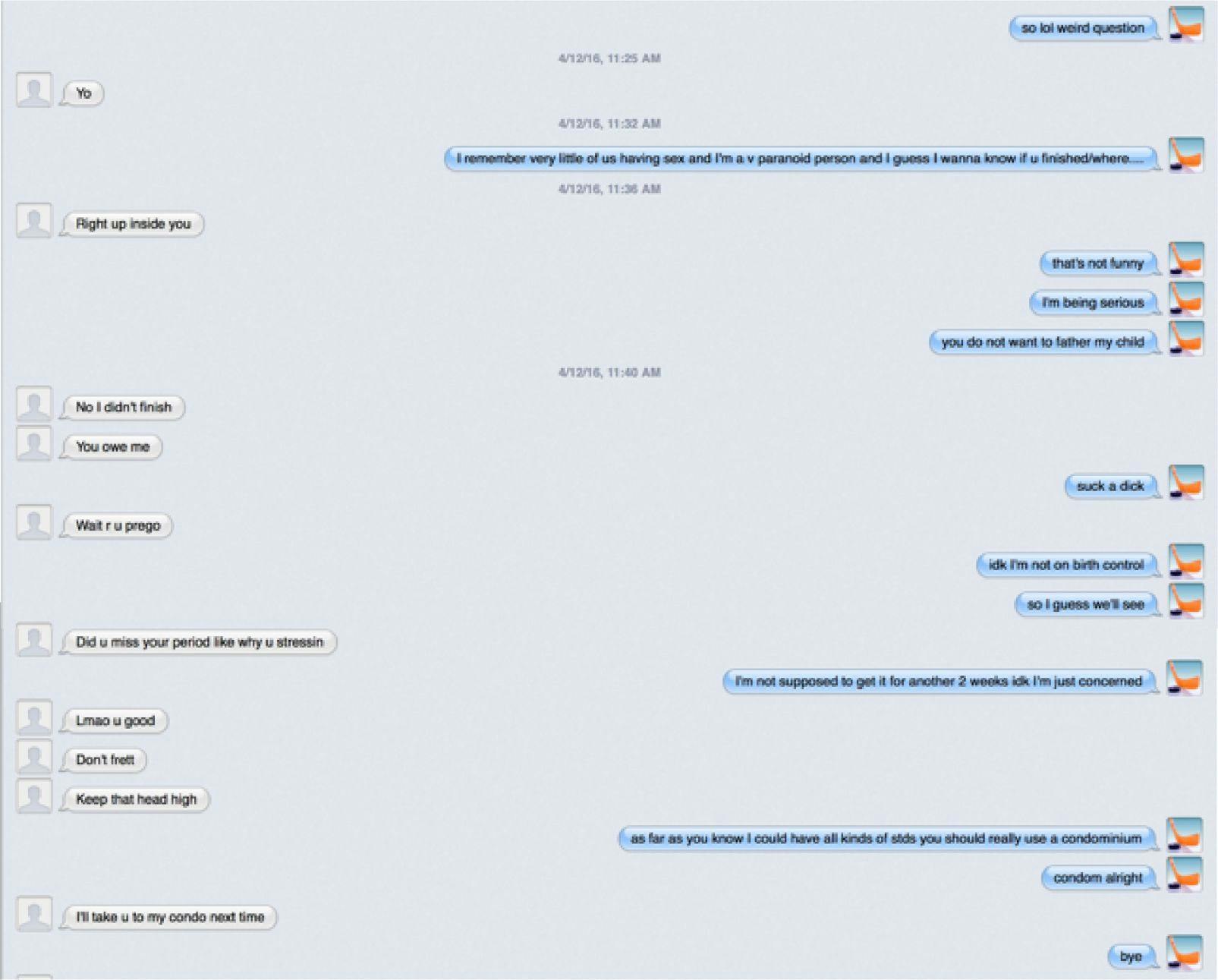

From his and Abby’s texts a week later, I would say no.

Abby and her date’s conflicting reactions (one frightened, one prideful) reveal a seldom-acknowledged truth about blackouts and sexual assault: While there may well be a shadowy space where alcohol meets sex and consent recedes into obscurity, that space is often only painful and traumatic for women to enter, not for men.

UF’s sexual assault survey discussed in my last column reflects this truth: if men and women both left these experiences with queasy stomachs, they would report sexual assaults at more similar rates. Backwards gender norms might account for some variation, but not sixteen percentage points, and certainly not when about two thirds of survivors in a Washington Post survey of undergraduates reported consuming alcohol before their assaults.

Perhaps this — that the brunt of the trauma affects women and not men — is why we don’t so much debate what should be done about blackout consent, but whether something should be done at all.

In a series of video interviews about consent from that same Washington Post survey, one student describes his take on asking for consent. “So does there need to be a verbal yes? I don’t think so, no." I think that’s unrealistic to think that every sexual encounter needs to have a (verbal) ‘yes’.”

His comments beg the question: what is realistic? Thousands of women getting raped? Is it really too much of an inconvenience to ask if you should reach for a condom before sex? We’re content shrugging because it’s a woman’s lot to cope with the consequences of a man’s mistakes. God forbid we trouble men not make them.

To respond here that women should just not enter that space, that they should either buck up or drink less, is to talk past my point.

Preventing crime runs parallel to — not together with — not committing it. We all lock our doors at night to prevent theft, but no one would suggest that a thief go unpunished because I failed to do so one night. Even asking someone to rob me does not make robbery less illegal.

Sex should not happen when either party remotely approaches incapacitation. Whether or not we can accurately define that point is irrelevant. Ambiguity does not justify inaction.

Is the legal limit for driving not an equally gray, equally arbitrary decision? When your blood alcohol content hits 0.08, do you suddenly lose the capacity to drive? Before you get in the car after a couple beers, do you run a quick breathalyzer test to be sure you come in under the limit?

We established a clear and measurable law and abide by it as best we can — tolerating the uncertainties that law inevitably contains — in an attempt at safer roads and sidewalks. When will we make the same sacrifices for the safety of a woman’s body?

Champe Barton is a UF economics and psychology senior. His column appears on Fridays.