Lennie Kesl would have been 91 years old next month, but we don’t have to wait to celebrate his life.

This Friday, the Black C Art Gallery, located at 201 SE Second Ave., will host a tribute exhibit in honor of Lennie, coinciding with Artwalk Gainesville, the self-guided tour of Gainesville’s galleries and businesses that support art.

The exhibit is free to the public, opening at 7 p.m. after a birthday party held in honor of Lennie for his friends and family, said Allison VanDenend, the director of the gallery.

Leonard Kesl, affectionately known as Lennie, born on June 12, 1926, was the Gainesville music and art community’s “favorite son,” according to his obituary. He passed away in November 2012 after creating a legacy as an artist, musician, father and friend to everyone.

This celebratory show has been in the works for many months. The founder of the gallery, Ani Collier, first wanted to build a show around Lennie back in September 2016. A commemorative exhibit was then planned around Lennie’s birthday, beginning May 26 and ending July 22.

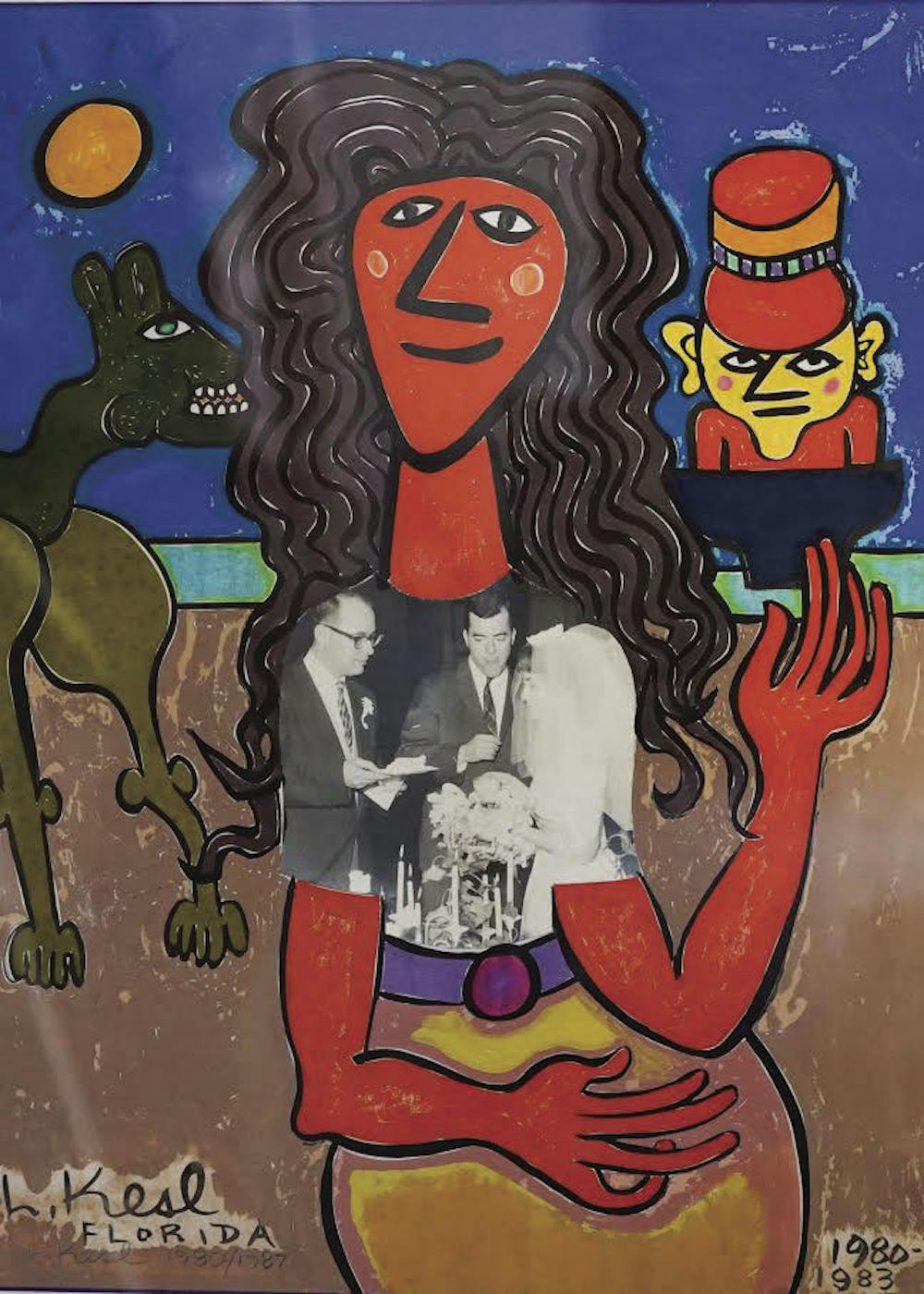

The exhibit will feature more than 30 works from a local, private collection. These will include paintings, ink drawings, etchings, collages and sculptures. Like all great birthday parties, there will be cake, VanDenend said.

“I didn’t have the pleasure of meeting him, but in doing all the research for the show, I think I know him and his spirit,” she said.

At the tribute, Lennie’s musician friends will perform some of his favorite songs, like “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Exactly Like You.”

One of those musicians is Cathy DeWitt, senior musician in residence at UF Health Arts in Medicine. DeWitt began playing music with Lennie in the early 1980s.

She said Lennie first played the drums in their band and would often be distracted by anyone who would walk in the door.

“He would sit at his drum set, and we’d be up on stage at some bar or club, and somebody would come in the door … and he’d wave his sticks in the air. One time, he literally fell off the stage doing that,” she said.

Anyone who knew Lennie could tell you about his wealth of knowledge about jazz music. He had an amazing memory for these kinds of details, his daughter Diana Kesl said.

“He was like an encyclopedia of jazz. He could name any musician, when he was born, when he died, where he played, what he played. He could even remember lyrics,” she said.

While Lennie might have been distracted while drumming, this wasn’t the case with his singing, DeWitt said. Every song he’d sing would never be the same twice. Because he developed relationships with the songs he sung, the emotions during these were all encompassing.

But his voice wasn’t exactly beautiful, she said. He had a raspy voice filled with emotion that didn’t hold back.

“It’s not (like) a crooner, like a Frank Sinatra or a Harry Connick (Jr.). It’s very unique. The thing that would really grab me about it is the emotion and the genuineness of what he was singing, what he was feeling,” she said.

Ironically, Kesl said her father thought otherwise.

“Music was probably his first love or a close love to art. He thought he was the next Frank Sinatra,” she said.

When describing her father’s art, the word happy usually comes to mind, Kesl said.

“He captures the spirit of humanity with his people, mostly ladies because he loved the ladies,” she said.

DeWitt reiterated that fact by saying that joy and vibrancy shine through his work, affecting whoever views it.

She recalled that after the Sept. 11 attacks, she found herself walking around feeling numb, depressed. But when she walked into an exhibit Lennie had at the University Gallery, she had a moment of revelation.

“I felt this energy, and it was the first time I felt joy again, and that was kind of a powerful epiphany for me that visual art can make you feel this way. I believe that people’s energy gets transferred into people’s paintings. And Lennie was like a bundle of energy,” she said.

Lennie projected humanity into the many mediums he took on. Kesl’s favorite medium of her father’s was his ceramics because of their functionality and beauty. She has some hung in her home.

“They’re just smiling down at me,” she said.

Relationships were important in Lennie’s life. Whatever was going on, he wanted to be a part of it, DeWitt said, and he made sure to remember details about people’s lives, leaving them notes or dropping off books that he thought they might have liked.

Some of the things that DeWitt cherishes are little handwritten notes with drawings and funny spellings of words on them that Lennie gave to her.

Kesl remembers how difficult it was sometimes to go out with her father because of the amount of time he would spend talking to people.

“When we’d go places, he was Mr. Congeniality. He’d know somebody, and he’d start talking to them. He’d remember their name. He’d remember facts about them even if he only met them one time,” she said.

The impact that Lennie left on the arts and music community in Gainesville is obvious. Local headlines hail him as “larger-than-life” and “irrepressible.”

His works can be found in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and all over the U.S. But, most of all, he was a local artist, a father and a grandfather who loved carrot cake.

He was a man who would run down rabbit trails, eager to tell you something.

“You’d say goodbye to him on the phone, and you’d be talking another 30 or 40 minutes. It was hard for him to say goodbye,” his daughter said.