Do you hear it? The ticking? She hears it. She’s been hearing it for as long as she can remember, and now it’s grown from a little pinch to a searing pain she can’t hide if she tries. She hears it when she thinks about her future — a future that, until recently, saw her heading to the WNBA. Well, no more. No more basketball for junior Brooke Copeland. Not when people are suffering, dammit, and not while she can do something about it in her limited time on earth.

On Monday afternoon, she walked into her final interview as a member of the Florida women’s basketball team. It wasn’t what she once imagined it’d be. There was no discussing where the former 10th-best high school post player in the country was going to play after graduation. There was hardly any mention of her UF basketball career. Instead, she talked about getting engaged. She hugged and waved and showed off her diamond to friends passing by. She explained why she was giving up basketball — the game she’s played since childhood — to try and make a difference in the world.

There were always signs that this was how her story at Florida would end. That the ticking had been going on for some time. Back in high school, for example, the star recruit was asked what she wanted to do with her life.

“Be a missionary to Israel,” she answered.

Then there was AnnaRose Van Sciver, a troubled 10-year-old who Brooke befriended at UF. She made it harder for Brooke to justify basketball, and when a story came out about their relationship in 2015, Brooke offered a hint at her future.

“It’s very difficult,” she said of continuing to play basketball before referring back to AnnaRose. “My heart is in that.”

There was also Brooke’s trip to Thailand in the summer of 2016, where she worked to help isolated communities by teaching kids and building a water container out of plastic bottles and concrete. There, the ticking became thunderous.

“There is so much need over there, and I’m here,” she said when she got back. “And I don’t wanna be here.”

The ticking became deafening around spring break. Around when UF women’s basketball coach Amanda Butler was fired. That’s when Brooke went to Butler’s house one day to baby sit her adopted son, Nehemiah, and told her about what had been building for several years. About the infernal ticking.

“I don’t wanna play basketball anymore,” Brooke told Butler, “and I feel like I’m at peace with it.”

Butler tried to convince her otherwise.

“I don’t want your basketball career to end like this,” Butler said. But she accepted it.

Since then, the ticking hasn’t stopped. It’s something Brooke said is never going to stop. It’s what pushes her to be the person everyone can always turn to, the person she is. It’s the reason — along with the grace of God — she’s overcome her own demons and downfalls. It’s the reason she’s giving up on basketball.

“One of my biggest fears in life is settling,” she said. “This life is so finite. We have such a finite amount of time to impact. But we have such a powerful opportunity for impact and for influence and to change people’s lives for the better…

“I just think that’s so freaking powerful. And for us to not use that impact and use that influence and that power is just a disservice to the world.”

• • •

Brooke wept.

Lying in a hammock in Wang Psra — a remote village in Thailand — last summer, the fact that she’d be leaving soon was already chewing at her. The realization that the village’s children likely never would leave forced her to tears.

“I just broke down and was just bawling crying,” she said.

Jakkajun, an 8-year-old Thai girl who Brooke called “June,” was sleeping in her lap when she was woken up by Brooke’s despair.

June was a crier herself, as one might expect of any 8-year-old. Throughout the trip, when she had fallen or scraped something or been afraid, Brooke had asked her — despite the fact that June spoke no English — “You OK?”

On the eve of Brooke’s departure, after wiping the streams of tears flowing down her face, June returned the favor.

“You OK?” she asked.

“I just started crying even more,” Brooke said.

She befriended other girls on her trip to Thailand as well. One of them was Mimi. Mimi never talked to anyone on the service trips, which cycled in and out of the village every few weeks. Brooke changed that.

“She’s the first person ever that can make Mimi and other kids actually come and hang out with us,” said Yanee Csaisawat, the program’s director.

“Brooke was almost like the Mother Theresa of all Thai kids,” added Kyle Bell, a UF telecommunication-news student who joined Brooke on the trip.

Brooke loves — and has always loved — helping children, but she realized the irony of her situation in Thailand. While she has the resources to help the children of this village and villages everywhere, the children don’t have the resources to help themselves.

Brooke said that June, for example, wants to be a teacher. Another girl named Im wants to be a nurse. And Mimi — the quietest one of the bunch — wants to be a singer or dancer.

They’re likely destined to be rice farmers.

“It just really broke my heart,” Copeland said. “I would cry all the time when I went to sleep at night just because I’m thinking these kids are so” — she paused.

“Why me? Why am I so privileged to be born in a country that I have so many opportunities? And especially here at the University of Florida,” she said. “They deserve it just as much.”

From that village, Brooke traveled down the Mae Taeng river to more villages with more people in need. She said the water looked like the chocolate river from “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” and she was armed with a homemade bamboo raft. Her skin shimmered from bug spray. The bathrooms in the new villages were holes in the ground surrounded by livestock.

She’d never been happier.

So when she returned from Thailand and immediately headed to an all-inclusive Cancun resort with her family, all she could think about was getting back. She could hear it again. Tick. Tick. Tick.

“I would much rather be uncomfortable, sweating in 106-degree weather with bugs all over my body and be genuinely happy just because," she said. "You’re not searching for anything else because you have everything that you need. And the realization of that, and then you try to come back, you’re like, ‘What am I doing?’”

• • •

Let’s go back. Back before Thailand. Standing outside the O’Connell Center after the game — almost any game — AnnaRose waited for Brooke. Brooke always came out to play with the 10-year-old, who’d overcome two heart defects and cancer. In her, Brooke saw herself.

Of course, she’ll tell you it’s not comparable. She’ll tell you that what AnnaRose went through is more difficult. More daunting. On a completely different plane. And she’s probably right.

After all, Brooke volunteers at hospitals and after school programs. She’s graduating college a year early. She’s been named to the SEC Community Service Team twice. She’s been profiled as a model for what people should aspire to. But when she finished playing with AnnaRose after games, Brooke would go home and break down, locked in a battle of her own.

Everything rained down on her during sophomore year. Her grandmother died unexpectedly. She suffered a concussion and couldn’t play basketball. She had relationship problems that, even now, she doesn’t like to talk about. She struggled with her body image — something she has struggled with her whole life. She wouldn’t leave her room. And she kept her mouth shut about it all.

“I wouldn’t talk about it,” she said. “Because you’re supposed to be perfect. You’re supposed to have this ideal life. This bubbly blonde girl.”

She turned to her faith for strength.

Raised as a Baptist in the small Tennessee town of Cleveland, Brooke spent the Sundays of her childhood in church. She went and prayed and repeated every week, learning the rhythm and repetition.

“That’s what I was supposed to do,” she said, “and I knew I was saved, and I knew what was right and what was wrong, and read the books and knew the verses and all that. But what is that? That’s the word religion. The self-righteous ‘do this and you go to heaven and don’t burn for eternity.’ It’s just fear and distortion.”

She came to that realization when she arrived at UF, where she no longer had to go to church. There was no more repetition. No more hellfire preaching. So she sat down and tried to figure out what she actually believed.

It came to her during the darkness. When she was at her worst, she said she found God there, waiting for her. Not abandoning her. Giving her peace.

“It’s wild,” she said, “and you can’t really understand it until you experience it.”

Around the same time, Brooke started to see the basketball team’s therapist. He’d been holding team meetings, asking players to be open, but Brooke never was. She’d crack jokes, listen and laugh instead. Coach Butler confronted her about it.

“You need to open up,” Butler told her. “It’s really unhealthy to hold everything in.”

Looking back, Brooke knows she was right. Brooke knows she was trying to hold down her emotional vomit.

“I just didn’t want people to know,” she said. “Because they don’t care, you know? Why would I want to put my problems, my struggles that I deal with internally, on them? It didn’t make sense to me.”

Butler mandated that Brooke see the therapist once a week. It did nothing at first, but then the concussion happened.

“I have no other option but to let it out now,” she told herself, “or I’m going to be in a terrible place that I don’t wanna be.”

She unleashed everything, and not just her college struggles. Everything. About how she always felt like an outsider because she was larger than her brothers and classmates. About how she was picked on in elementary school for being fat. About how, as a result, she developed an eating disorder in seventh grade.

And she didn’t just tell the team therapist. She told her friends. Her coaches. Her teammates. She calls it learning — and loving — to be vulnerable.

“You’re not really living fully,” she said, “until you’re vulnerable with people that love you and care about you.”

But in addition to her newfound vulnerability, all that baggage had another effect on Brooke. It was something that had been there since the beginning. Something she can’t pinpoint exactly, but that seems to have been brewing beneath the surface forever. The origin of the Tick. Tick. Tick.

Because she’d been teased, Brooke tried reaching out to other outsiders. She fought back (verbally) for kids with disabilities. She sat with the loners at lunch. When she saw kids come to school with damaged clothes or without having showered, she pleaded with her mom.

“We need to help them,” she’d tell her.

That way of life still comes through today. It’s what drew her to AnnaRose, to Thailand and to everywhere she’ll go in the future.

“My entire life, I have never liked myself. Never. I still struggle with it today,” she said. “And it’s so much better, but it’s a never-ending process of learning to love yourself. And that’s a huge reason why I am the way I am with other people. Because of the internal battle that I’m constantly fighting within myself.”

• • •

Remember the ring? The one Brooke showed off to her friends during her last interview as a UF basketball player? It was given to her by UNC basketball star, ACC Player of the Year and guaranteed first-round NBA draft pick Justin Jackson.

The two have known each other since their junior years in high school, when they met playing AAU ball. Justin slid into Brooke’s DMs.

“You know,” she said, “how every prosperous relationship begins.”

They started dating in senior year before taking a break in college. Although they had never lived close to each other — he was from Texas while she was in Tennessee — the divide between Gainesville and Chapel Hill was deeper than they expected. They got back together in their sophomore years.

This year, as Justin was making a run through March Madness with the Tar Heels, Brooke was contemplating leaving the game. She’d talk to him about it, but she worried it was stressing him out and making him lose focus during the tournament. He reassured her with the same promise over and over again.

“Everything’s gonna change after the tournament,” he'd say.

That made her suspicious, and rightfully so. She told her teammates she was getting married.

Justin, meanwhile, lied about going to meet an agent in Atlanta, instead flying to Tennessee to meet with Brooke’s parents and tell them his intentions. So when Brooke told her mom of her suspicion, her mom told her to stay calm. It was probably nothing. She also called Justin and told him to tone it down. He was giving too much away.

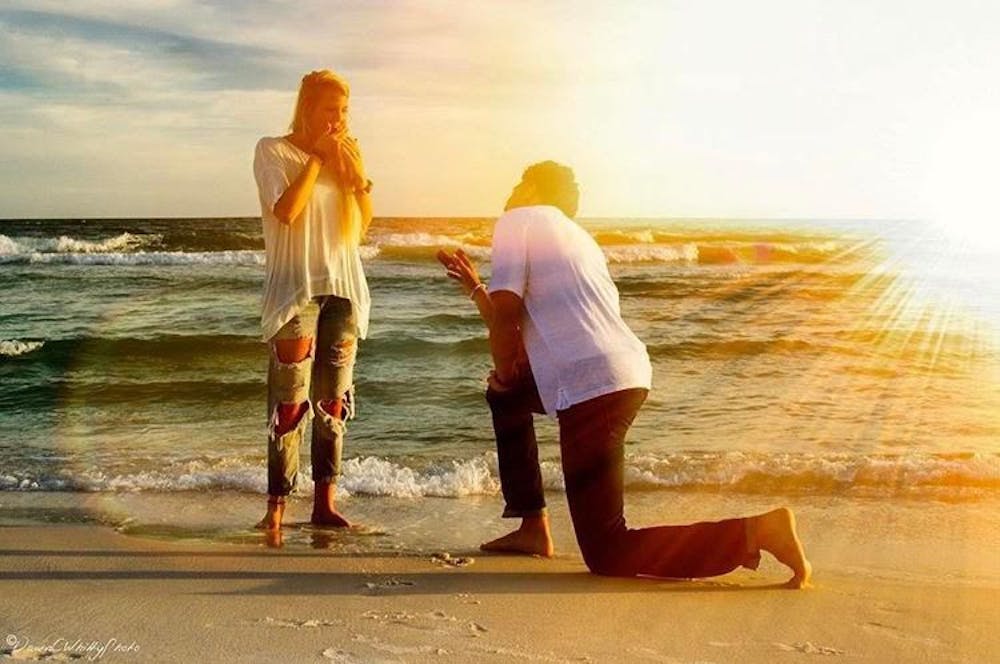

When the day finally came on Easter, they were at Seaside Beach in Florida’s panhandle with Justin’s family. Brooke was told there was going to be a family photoshoot and thought she’d be the one taking the pictures. Then she found out she was going to be in them.

During the shoot, Brooke was taking a break to talk to one of Justin’s sisters when he strolled over and dropped to the ground. This was it. The moment men wait for. The moment women dream of.

“Uhhh,” he muttered, knee in the sand, sun setting in the blazing orange sky, “I’m really dumb.”

He later revealed that he was trying to think of something smooth to say, but it didn’t come to him in the moment. And it didn’t matter. Brooke said yes to “I’m really dumb” and watched her family come out of hiding to congratulate them.

“It’s memorable for sure,” she said.

They plan to get married in September before the NBA season. After that, they’ll be living in the same state for the first time in their four-year relationship. But Brooke doesn’t plan to stay at home much, which is something Justin had trouble accepting for a while. Their relationship had been long distance for so long, and now, even while married, he couldn’t see her?

Brooke was uncompromising, and he changed his attitude. Now, he supports her mission — what she plans to do after she graduates this summer with a degree in telecommunication: found a global non-profit organization that focuses on helping kids all over the world.

For now, she’s focusing on east Africa — Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, etc. — because she’s spent a year learning Swahili and wants to use it. After not being able to talk to the kids in Thailand, she wants to make sure that’s not a problem again. There, she hopes to avoid building orphanages, which she likens to prisons, and instead build something like day cares, where she can help kids from struggling families as well as orphans.

There’s still, of course, the question of why. Sure, there are some answers to why this is what she wants to do. She doesn’t want anyone to feel alone like she did. Jesus demands it. She was raised that way. Etcetera. But that’s all subliminal. She could, theoretically, ignore that if she wanted to do something else like, say, play basketball. Why doesn’t she?

If you ask her, she’ll tell you it’s because she always wants more of everything. More relationships. More vulnerability. More life.

“We’re constantly longing for something more than what we have,” she said, “which is so smart. Because this world is terrifying. This cannot be it. This cannot be what we were made to live in. There has to be something more. There has to be a beauty and a light to come at the end of all of this.”

Brooke believes that the light will come from God, but she sees it shining in people. That’s why she smiles at everyone. Why she spends weekends tutoring kids instead of doing her own work. Why she hears the ticking getting louder and louder, pushing her to be more of herself and experience more of life every day.

Contact Ethan Bauer at ebauer@alligator.org or follow him on Twitter @ebaueri.

Former UF basketball player Brooke Copeland is proposed to by boyfriend and UNC star basketball player Justin Jackson on April 16, 2017, in Seaside Beach, Florida.