A portion of this article has been removed due to conflicting information between sources.

Blood. Flesh. Ink. History.

All these mark Caitlin Kantner’s body.

Her seven tattoos — scattered across her back, leg, ankle and behind her ear — include a U.S. Founding Father, American Revolution seals and an epic 18th century battle between a pirate and a British Navy ship.

The tattoos aren’t just a tangible history lesson. The tattoos are a tribute to LGBTQ+ figures throughout the 18th and 19th centuries — a topic that’s considered taboo in the history community and one that Kantner plans to get her doctorate in and create classes for.

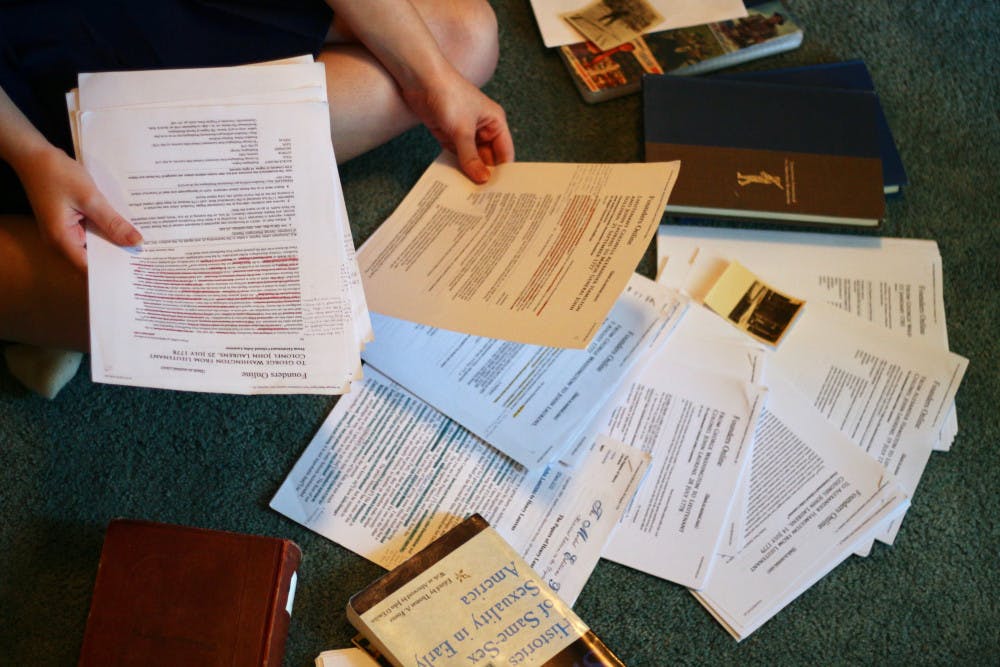

As she sifts through hundreds of first-person documents to make LGBTQ+ history more accessible, she’s continuing to tell the unknown and often forgotten stories of queer historical figures on her body.

“Your body is a canvas,” the 20-year-old said. “I’m telling a story with my tattoos.”

History has always been a part of Kantner’s life.

When she was 6, she was enamored with Egyptian history and begged her mother to take her to see the traveling King Tut exhibit in Fort Lauderdale.

When she was in middle school, she chose to play the flute because it was made by William S. Haynes, the founder of one of the first flute companies in America.

Since the UF history sophomore moved to Gainesville from Boca Raton when she was 3, she’s decorated her bedroom with furniture and knick knacks from various time periods.

Kantner has a suitcase from the 1950s she fashioned into a nightstand and a dresser from the 1860s she bought from a strange man off Craigslist. On top of that dresser, she keeps her collection of vintage coins that hail from African countries, the Caribbean, France, Germany and American time periods.

The only window in her room is covered with shutters to protect the delicate photographs from the 1930s that are taped on her wall.

In the photos, there is a lineup of newspaper boys from Gainesville and a portrait of a young girl. A replica of the Mona Lisa hangs under a ceiling painted like the sky.

Copies of “Common Sense” and “The Federalist Papers” are stacked next to her bed, which is crafted with raised wooden planks that run slanted to resemble a pirate hideaway, but she keeps her stack of treasured books tucked away.

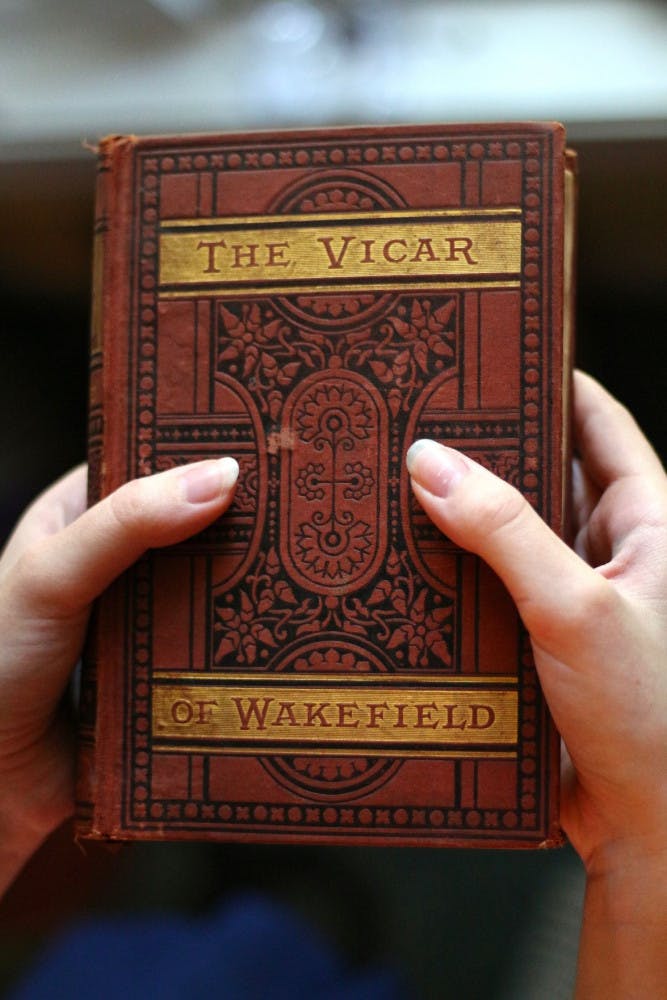

Among her 23-piece collection of rare books, which range in age from 1820 to 1950, is a leathery first edition of “Little Dorrit” and a copy of “The Republican Party.” She cradles each book close to her body and uses both hands to examine and flip through the yellow and weathered pages.

Pink butterflies hang below a mural of a golden road that becomes obscured by hills and trees that her mother painted for her when she was 10.

“When I was younger I was obsessed with roads leading to nowhere, which seems like a metaphor for my life,” Kantner said.

A career path as a historian never seemed like a possibility for Kantner who excelled in mathematics and was pushed by her peers and teachers toward careers in medicine and science.

“Why am I forcing myself to do something that makes me miserable?” she said. “I want to wake up and look forward to every day and love what I do.”

Deciding between choosing a field that interested her and one that was financially secure, she struggled with expressing herself in eighth grade. Confused about her attractions she had toward girls and boys, she was never exposed to any queer people until her U.S. history teacher introduced her to Alexander Hamilton.

The primary documents Kantner’s teacher gave her showed evidence that Hamilton, who married Eliza Schuyler, had relations with fellow revolutionary soldier John Laurens.

Learning about Hamilton helped Kantner identify as pansexual, which is a more fluid sexuality where her preference of sexual partner is not limited by gender.

Hamilton ignited Kantner’s passion and desire to study the American Revolution and bring to light queer figures in history.

“That’s why he’s memorialized on my leg,” she said, referencing the colored tattoo on her left thigh.

She even paid her respects to Hamilton’s grave in Trinity Church Cemetery when she went to see the popular broadway musical, “Hamilton,” based on the founding father in New York City last December.

Standing in an empty cemetery in early winter, Kantner couldn’t speak as she looked at Hamilton’s marble grave.

She thought about saying something to the man who has influenced her life even centuries after his death, but she decided against it. She doesn’t believe in ghosts. Hamilton is either gone for good, or he has been reincarnated, she said.

What matters to her is how she can pay her respects to the father of the national banks through her research and studies.

“He was a real person,” she said.

Caitlin Kantner holds “The Vicar of Wakefield,” a book published in the 18th century and stated she likes the outside of the book the best.

Kantner has planned her body art since she was 13.

But you would never know she has seven tattoos if you see her in a T-shirt and jeans. Her sparkled winged eyeliner and seven piercings that line each ear seem like the only accessories on her, but ink lurks beneath her clothing.

In the past two years, she’s undergone about 20 hours under a tattoo needle and paid about $2,000 for all her artwork. Before she sits down for each tattoo session, she eats a few Starbursts and some black licorice.

Tucked behind her right ear is a seal of the East India Co., the first charter company to colonize America.

Her ankles are left as tributes to her favorite history video games. Her left ankle sports an Assassin’s Creed symbol, an homage to the video game that introduced her to the Golden Age of Piracy, and her right is marked with an Infamous Second Son symbol, another action adventure game.

Her right hip is given to the pirates with the Queen Anne’s Revenge flag and the Jolly Roger flag, which is a skull above two crossed swords. Her left leg pays homage to Alexander Hamilton with his portrait — the one found on any $10 bill.

The most recent and elaborate is a colored tattoo that covers her entire back and depicts a scene from the Capture of the William where Captain Calico Jack’s pirate ship and a British war ship battled off the coast of Jamaica.

Kantner said the pirate captain was known for his Jolly Roger flag design and for having two female pirate crew members, Mary Read and his lover Anne Bonny who also had sexual relations with Read.

“Mary Read and Anne Bonny dressed as men, and Mary was documented as being bisexual,” she said.

Kantner still has one more session to complete the scene where her artist will add lighting strikes to the battle. Even though it’s the final piece for her scene, Kantner said she’s not looking forward to her tattoo session.

“White ink hurts the most,” she said.

Her mother, Catherine Kantner, nods her head in response. The stay-at-home parent is the one who helps her daughter change her bandages and keep her skin clean after each session.

Catherine Kantner said she was not fond of the idea of her daughter wanting tattoos at first, but she’s fine with them now.

“It’s your body; you do with it what you will,” the 52-year-old said, “and she’s telling a story.”

Caitlin tugs on her long, wavy brown hair that is fashioned into pigtails with pink and blue bows.

Her brown eyes fall to her Alexander Hamilton tattoo that’s covered by denim.

“I thought tattoos were just another form of expression to show what you believe in and what you feel dear to,” she said.

Capture of the William, a tribute to the Golden Age of Piracy is depicted on Caitlin Kantner's back. This Capture of the William, which depicts a battle between a pirate ship and a British warship, tattoo cost $1,000.

Kantner wants to go to Columbia University and earn her master’s and doctorate so she can make LGBTQ+ history more accessible to students. She even plans to create an advanced-placement course so high-school students have access to LGBTQ+ studies.

“I would want LGBTQ students to realize that they are validated,” she said.

Caitlin Kantner stands in front of her book chest where she keeps her rare book collection, which houses 23 books.

Kantner still has a long journey ahead of her.

She’s got two more years to collect more rare books, write LGBTQ+-related research papers and design another American Revolution tattoo that flows down her sternum to her stomach. She has decided that she won’t plan out any tattoo sleeves until she has tenure at a college, preferably one with a rich history such as the College of William & Mary, Princeton University or Cornell University.

As a historian, she’ll continue to interpret primary documents and give queer people recognition — that’s why she said history is so important.

“History is personal,” she said. “We’re looking to tell our own stories through the people that we do study.”

She said the bridge between past and present can be blurred because of the immersion that is required when studying a person.

You learn every detail about them, she said. You listen to the music they listened to, you eat what they ate and you can even dress how they dressed, she added. And she’s often brought to the same realization after learning about her subjects.

“They’re painfully human,” she said. “No matter where the person you’re studying came from, at the end of the day, they faced struggles that we face.”

Caitlin Kantner looks through letters from John Laurens and other collected information, which she has gathered for her honors thesis.