Alex Faedo is early.

He’s relaxed. He’s talking about his hometown Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He’s talking about how he slices golf ball after golf ball. He’s talking about the Atlanta Falcons playing in the Super Bowl.

But then the interview begins, and the talking stops.

He doesn’t seem nervous as his 6-foot-5 frame hunches over an elementary school-style chair and answers question after question with one-sentence answer after one-sentence answer. He doesn’t seem disinterested. Yet, the room turns from interview to interrogation, with each question drilling for oil and coming up dry.

Eventually, after 30 minutes of back and forth, four important details emerge about Faedo, the ace of Florida’s baseball team.

First, he prays before every game. He won’t say about what.

Second, he doesn’t have any tattoos. His dad never wanted him to have tattoos.

Third, he sometimes shrieks after earning important outs. He learned that — personally — from José Fernandez.

And fourth, come June 12, he’s going to earn more money in one day than many people earn in their lives.

As the potential first overall pick in the MLB Draft, Faedo could pocket a signing bonus of more than $9 million. He could also be the first Florida player to be selected first overall. But he doesn’t like to talk about that — not with a reporter or anyone else.

He prefers to talk about something — anything — else.

Before the interview, for example, he chatters about how the Bucs should have drafted Adrian Peterson fourth overall in 2007 before revealing that he wants Tampa Bay to sign the aging running back now.

“When he’s old and falling apart?” he’s asked.

“That’s fine,” Faedo responds. “He’s got heart.”

• • •

Alex sprinted toward the car.

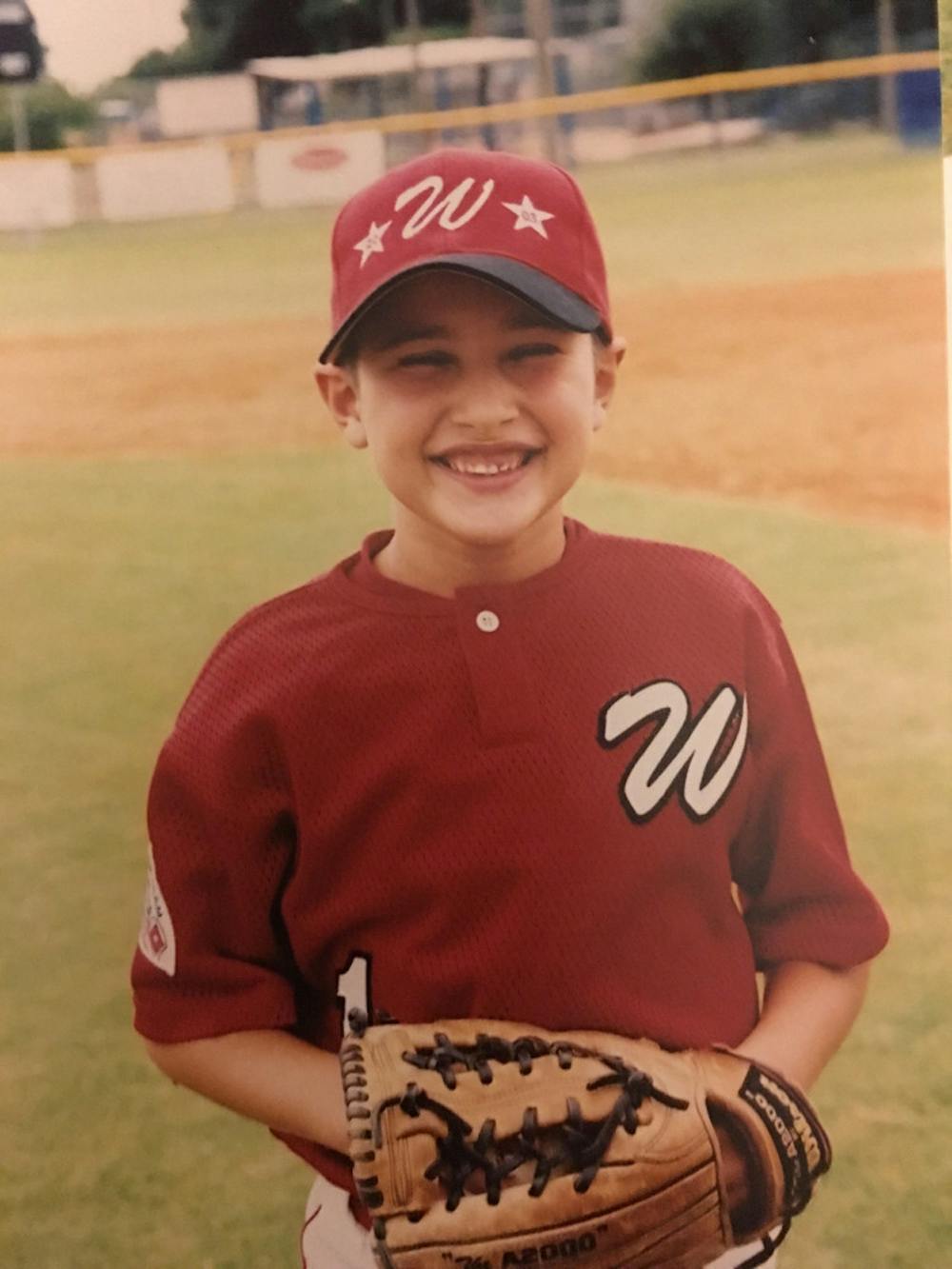

On and on, he described how much fun he’d had in his first little league baseball game.

“We thought he was so happy because they won,” Faedo’s mother, Kristie Donovan, said.

But after more chatting with the then-4-year-old Faedo about the excitement of playing, he surprised his mom with an unusual question for a kid who, minutes earlier, had watched the end of his team’s game:

“Who won?”

More than 15 years later, Donovan can’t forget that moment. It was the first of many little league accomplishments that eventually set Alex on a path for major league stardom.

“He was just so happy,” she said, “because he got to play, and he had a good time.”

While that was Faedo’s first formal baseball experience, it wasn’t his introduction to the game. That came as a 2-year-old in his backyard.

Faedo’s father, Orlando Faedo, had played or coached baseball for much of his life, and he wanted to introduce his son to the game early. So he bought a black plastic bat with former major leaguer Wade Boggs’ name emblazoned on the barrel to play wiffle ball.

For hours, Orlando tossed the wiffle balls to Alex, with the rhythmic whack, whack, whack of plastic meeting plastic serving as the soundtrack of their afternoons together.

Orlando himself was a baseball player, though he was never taught the game by his parents. He just loved sports, playing whatever was in season — baseball, basketball, football, etc. — when he was a kid.

He played baseball at Hillsborough Community College and St. Leo University, where he studied physical education. He wanted to play in the pros like his cousin, Lenny Faedo, a first round pick on the Minnesota Twins in the 1978 draft who played five years in the majors. But Orlando never made it.

Instead, he decided to stay around the game by coaching, both in high schools and with his son.

Alex’s mom, meanwhile, found another way to enjoy sports with Alex.

Whenever she would take him to their community pool or their pool at home, he never wanted to go in the water. Instead, he just wanted to toss a spongy pool ball colored various shades of highlighter back and forth.

Alex and his mom did this for years, constantly playing a game to see how many times they could throw it back and forth without dropping it.

“I always think back to that and think, ‘Oh, I guess all kids like to do that,’” Donovan said. “But then when I had my second son, I realized that most kids who go to the pool just wanna play in the pool.

“He was never like that.”

She also said she’s never caught him lying. When he was in kindergarten, he would get in the car and announce he’d gotten in trouble before anyone asked.

He played video games, lived in a cluttered bedroom covered in sports memorabilia and competed in every sport he could. And sometimes, when it had just rained and thin puddles dotted the nearby Westchase Golf Course like freckles, Faedo and his friends would ride through the grass on skimboards.

But as Alex grew, so did his involvement in baseball.

His dad remembers bringing him to games at UF’s McKethan Stadium. The head coach at Tampa’s Alonso High School, Orlando remembers one time when they came up to watch his former pitcher, Tommy Toledo, play for the Gators.

Just before the national anthem, Orlando told Alex to go stand with Toledo on the field, as many kids were doing.

Alex shook his head.

He was never shy when it came to his feelings about the game, though.

His mom remembers one time when he was about 12 and the family was packing for vacation. Alex had to have his glove with him. No matter where the family went, he always had to throw. So his mom tossed the glove into the car, immediately noticing the look of terror on Alex’s face.

“Mom!” he yelled.

“What?” she answered.

“You can’t just throw my glove in there like that!”

“It’s a baseball glove…”

“You can’t just throw it around like that! I had it exactly like I wanted.”

That moment leads to jokes to this day, with Donovan always making sure to treat her son’s gloves like “a fine piece of china.”

Alex took his performance on the diamond just as seriously, playing for some of the state’s top teams in some of the nation’s top tournaments by the time he got to high school. However, he didn’t pitch much. His body wasn’t developed enough, his dad said, until halfway through high school.

Instead, Alex, whose little league teammate Jake Clark described as “tall and awkward,” played mostly first base.

He didn’t hit a home run until he was 10.

But Donovan still keeps that ball — along with about 50 others — in a closet with too many trophies to count along with various plaques and ribbons. She’s still constantly adding to the collection, with some of the balls coming from UF and elsewhere.

Many of the others are game balls awarded to Faedo for the standout performances of his youth, which he earned despite Orlando’s description of his son as an “average Joe.”

“I probably have a hundred of them,” Alex said. “Like, not saying I did that well. I just probably have a couple of them sitting around.”

• • •

Alex watched his teammate sprint around the bases.

Trailing by a run and down to its last three outs, José Fernandez had put Alonso ahead in the top of the seventh inning. Then, in the bottom on the seventh, he went out and finished the opposition on the mound, propelling the Ravens to the state championship game.

Alex looked on from the dugout.

He was a freshman when Fernandez was a senior. But he modeled himself after Fernandez’s passion, competitive spirit and, of course, his success.

In addition to leading Alonso to the state championship, Fernandez had also set the single-game strikeout record (16) in the Tony Saladino Tournament, which pits Tampa’s best baseball programs against each other.

Faedo broke that record with 17 in the first start of his junior season.

“He was happy,” Orlando said of his son besting Fernandez’s record, “but he wasn’t boasting about it.”

That combination of dominance and silence is something that Faedo still embraces today.

Clark, for example, says that sometimes he’ll text Faedo about how well he threw in a game.

“He’ll go like seven innings, no runs and 10 K’s. I’ll text him and be like, ‘Dude, you looked awesome out there,’” Clark said. “He’ll be like, ‘Eh, I kinda let a few pitches get away.’”

Faedo’s roommate Dalton Guthrie, meanwhile, said Faedo regularly glorifies opposing pitchers in the dugout but can’t recognize their traits in himself.

“We’ll be watching a game and there’ll be a guy pitching, and he’ll be like, ‘Oh my gosh, this guy’s incredible,’” Guthrie said. “And I’m like, ‘He’s got the same stuff as you.’”

Alex Faedo pitches during Florida's 10-4 loss to Mississippi State on April 9, 2016, at McKethan Stadium.

And Faedo himself gets visibly annoyed when asked about whether he enjoys attention from people for his baseball skills, though he’s quick to point out that people don’t often ask him.

“I just don’t want people to try and be fake and just come up to me and try to ask about baseball and try to be like, ‘Oh, you’re doing good. I hear great things,’” Faedo said. “I just wanna say hi and go get my food.”

Comments and questions like these became more common after his performance in the Saladino Tournament. That performance is also what put him on a path leading to UF, the school he always wanted to go to. But aside from perfecting his pitching, Alex also prepared for Florida in other ways.

He was always watching games on TV, Clark said, trying to learn and improve. He was also the guy who would make other people finish runs when nobody was watching. And under Faedo’s father at Alonso, there were plenty of opportunities to run.

Orlando didn’t tolerate taunting, mocking or misbehavior of any kid, whether on or off the field, according to both Faedo and Clark. When asked how much he made his players run, his son described it as “a legal amount.”

“Obviously, in the moment, you’re like, ‘Oh man. This is crappy,’” Faedo said. “But when you’re done, you’re like, ‘All right, that was worth it.’”

• • •

Alex Faedo is late.

He’s shuffling across the concrete floor underneath McKethan Stadium with his heels sticking out of his shoes, grinding his metal cleats. Eventually he stops, tying triple knots in both shoes before heading toward the team’s preseason photoshoot.

“Just now,” Guthrie explains, “he got here late because he was volunteering over at the elementary school.”

But out of hearing range of his roommate thanks to the hiss of nearby pressure cleaners, Guthrie is struggling to explain something else. He’s asked about his favorite memories involving Alex.

“Hah,” he says, “Goodness.”

He giggles. “Lemme think.”

“There’s a lot,” he says before letting out a loud laugh.

“I don’t know which ones are appropriate.”

He eventually settles on their trips to Asia and Cuba as part of the Team USA baseball program, concealing whatever he was laughing about. He also points out that while people know Alex as the superstar baseball player — the one who could fulfill his little league dreams and go first overall — he’s not just about baseball.

“Everyone sees... the baseball side,” Guthrie said, “but there’s more to him than that.”

To Guthrie, the “more than that” starts with Faedo’s interest in working with kids and giving back to younger players. Alex donates many of his old gloves to current Alonso players.

There’s also his interest in the outdoors. He loves to go to places like Ginnie Springs with his friends.

And then there’s the pair’s obsession with video games.

Alex keeps two PlayStations in his room at the Keys Residential Complex, which he’ll use to beat Guthrie in NBA2K and lose to him in Call of Duty.

“All we do is sit at home and play video games and play baseball,” Guthrie said. “That’s our life.”

Other than the PlayStations, Guthrie said there’s really nothing remarkable about Alex’s room. It’s basic, he said, with nothing on the walls and little clutter.

It contrasts his childhood bedroom, where Faedo kept bobbleheads, signed baseball bats and posters.

Clark remembers one of those posters — the one just to the side of his bed — more than the rest. It’s a portrait of the Tampa Bay Rays locker room with jerseys hanging throughout. All of them were the star players of Alex’s youth, except one: No. 7, Faedo.

Florida pitcher Alex Faedo has been playing baseball since he was 2 years old. Come June 12, he could be UF's first ever first overall pick in the MLB Draft.