To protest a 515-mile natural-gas pipeline set to cut through Florida, a St. Petersburg woman will dance across the state, shimmying through Alachua County on her way southbound.

A devout believer in Mother Nature, 32-year-old KC Cavanaugh considers herself to be a protector of the water, a natural resource she thinks the Sabal Trail Transmission pipeline may contaminate while it cuts through Alabama, Georgia and Florida, including tracts of land near Gainesville.

“I’m hoping that just by bringing awareness… it will help in some way,” she said

She isn’t alone.

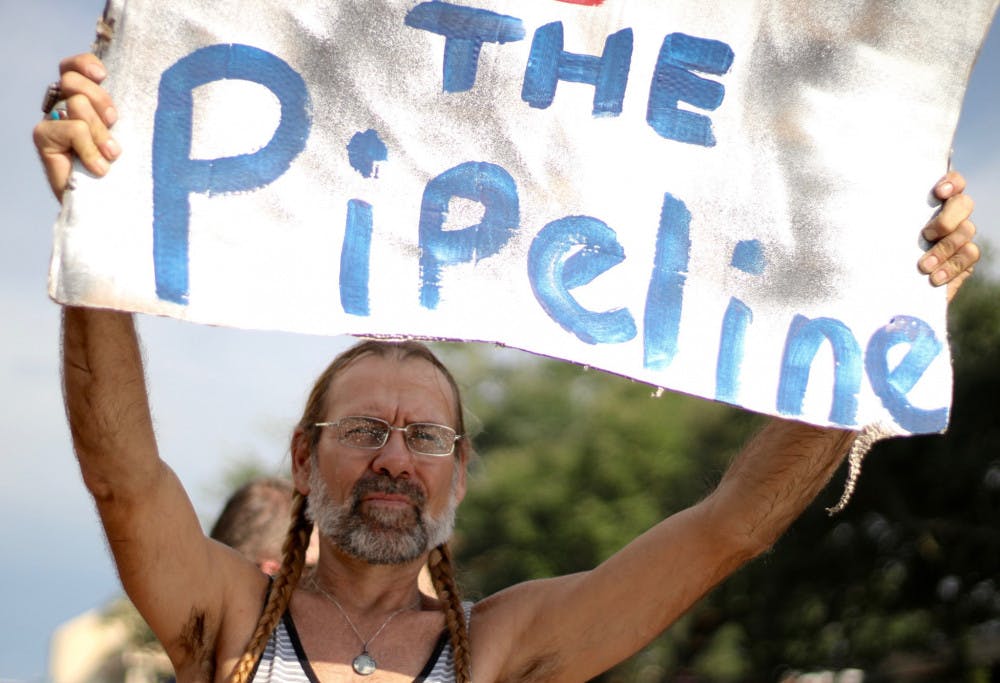

In recent months, hundreds of protesters across Florida — including in Gainesville — have decided to rail against the pipeline, a project put into motion by Florida Power and Light that will pump 1 billion cubic feet of natural gas every day.

Residents have organized rallies, written state legislators and hosted town hall meetings opposing the pipeline, scheduled to be operational by mid-2017.

“It’s great to have public participation,” said Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson, an organizing representative of the Sierra Club of Florida. “You can’t do it with just 10 people.”

• • •

Less than a month ago, when Christine DeVore Santilo learned her neighbor’s land would be seized for pipeline construction, she felt like her land was being taken, too.

Santilo, 52, said she had hoped to refinance her house in Williston Highlands, Florida, but she is afraid property values in her area will plummet due to the construction and the possible environmental side effects that come with it.

Although she is still waiting on a notice or town-hall meeting informing her when construction will start, she said she heard construction has already begun in the city of Live Oak, about an hour from Gainesville.

“It’s very unsettling, because I have no idea what’s going on with it,” the UF radiation oncology researcher said.

About three or four years ago, Santilo’s husband, Francis, 51, was living alone on the property and confronted pipeline surveyors in his yard.

Little did the survey crew know, they were standing on one of his cats.

One of the concerns Francis Santilo had for the pipeline going through his land was his pet cemetery, where he buried several of his pet cats and dogs when they died.

Although his plot was spared, he said the pipeline’s threat to the surrounding water and air remains a concern.

Living in a rural part of Alachua County, the Santilos get water from a well. After hearing reports of pipelines in the U.S. bursting, Francis Santilo said he is worried about Sabal Trail leaking gas into Florida’s aquifer and affecting his drinking water, despite statements from the company and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection saying the project would be safe. He said he is also concerned he’ll soon be sitting on a piece of dead ground no one would be willing to buy.

Sabal Trail began negotiating for land in September 2014, and as of March, it had filed for eminent domain on 160 properties in Alabama, Georgia and Florida, according to an Orlando Sentinel article.

While the land would typically return to the landowners after construction, some private property can be permanently seized through eminent domain — the government’s right to take land for public interest — when property owners cannot reach an agreement with pipeline officials, according to Sabal Trail spokeswoman Andrea Grover.

“The little guy always pays,” Francis Santilo said.

• • •

Many environmentalists argue the land taken usually becomes irreparably damaged. The pipeline’s proposed path runs through sinkhole-prone areas, people’s homes and state parks, causing concern for the safety of residents in those areas.

“Even in the unlikely event that a sinkhole opens beneath the pipeline, the pipeline can safely span distances exceeding 100 feet,” Grover said, adding that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission found it unlikely that the pipeline would impact Florida’s water.

Despite the reassurance, Floridians continue to express concerns with the pipeline possibly leaking and releasing chemicals into the drinking water supply.

“We have fought for generations against pipelines in the water supply. We have gone to blows over it,” Malwitz-Jipson said.

• • •

Even though many protesters acknowledge their voices may not be enough to stop a multimillion-dollar company’s vision, they feel it is their responsibility to spread the word to as many people as possible.

But in a state where natural gas dominates electricity production, according to UF’s Florida Energy website, some acknowledge there is little that can be done to halt construction.

Considering accusations that the pipeline would threaten local environments, Grover said natural-gas pipelines are among the safest forms of safety operations.

“Our safety programs are designed to prevent pipeline failures, detect anomalies, perform repairs and often exceed regulatory requirements,” she said.

• • •

At a recent rally in Gainesville, Mike Roth and a few others sang “This Land is Your Land,” a song that represents their struggle.

However bleak the chances of stopping Sabal Trail are, banding together is what his conscience tells him to do.

“This is just our desperate attempt,” he said.