In 2006, UF made a promise to reach zero waste by this year.

“Zero waste” means that 90 percent or more of the waste collected can be diverted from the landfill and be reused, recycled or composted. There will always be that 10 percent that cannot be reused in any manner, such as biomedical waste or liquefied trash.

But last year, UF diverted only 45.3 percent.

Although the university has a long way to go, efforts in generating a sustainable university haven’t been wasted.

The idea for zero waste at UF was conceived in September 2000, when the university established an Office of Sustainability in the College of Design, Construction and Planning.

The zero-waste idea then traveled to The Swamp, when the University Athletic Association implemented the idea in the stadium’s skyboxes, said Dedee Johnston, Wake Forest University’s director of sustainability since 2009 and former UF sustainability director.

In Feb. 2006, UF created the campus-wide Office of Sustainability. Its goals: to be carbon neutral by 2025, to add sustainability studies to the curriculum and to create zero waste by 2015.

Johnston said that it was important for UF as a flagship campus to take on these “big, hairy, audacious goals” in order to influence other Florida campuses.

Matthew Williams, UF Office of Sustainability director since 2013, said a zero-waste goal is forward-thinking. A 10-year time horizon was pretty long for a university to have, he said, but was short enough for people to get motivated and engaged in the idea.

“It’s a tricky one because everything we do is heavily dependent on what’s available in the community,” he said.

Diverting waste successfully is linked to the county’s ability to process, recycle and compost. It’s difficult to achieve a university zero-waste goal when there isn’t a large-scale composting facility.

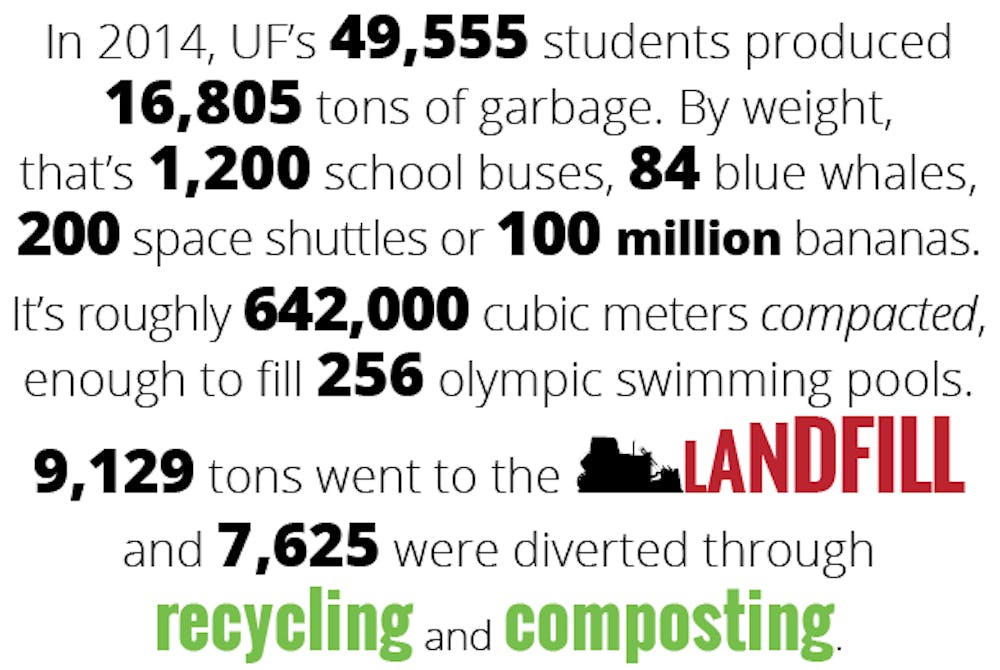

In 2014, of the 16,805 tons of combined waste produced by UF’s 49,555 enrolled students, 9,179 tons were sent to New River Regional Landfill, which is about an hour away in Raiford, and 7,625 tons were diverted through recycling and composting.

“Right now, we’ve rebranded it as ‘toward zero waste’ to give us a little more wiggle room,” said Liz Storn, a program coordinator for the UF Office of Sustainability. “But it’s definitely possible.”

HOW UF MEASURES UP

UF is one of 701 institutions participating in the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education’s program called Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System, known as STARS. Schools can earn bronze, silver, gold or platinum ratings.

The association system rates schools based on a checklist of tasks, which includes education initiatives, building design and waste diversion. UF had a silver rating in 2011, but it has since expired. Storn said the Office of Sustainability is working toward resubmitting its information to have a rating by the summer. Storn said the ratings last three years, and they hope to be rated silver or gold.

The Ohio State University, whose stadium in 2011 became the largest in the country to attempt zero waste, has a silver rating. OSU has a 34.4 percent diversion rate on the nearly 58,000-student campus and an initiative to create zero waste by 2030, said OSU’s sustainability coordinator Tony Gillund.

Its stadium can hold about 16,000 more fans than The Swamp, and OSU’s highest diversion rate at its football games is 98.68 percent. In its 2014 season, it contributed 1.95 tons of waste to the landfill, according to its website. UF has been gearing toward being waste-free in its football stadium by starting a recycling program in the 2006 football season and has a 70 percent average diversion rate.

Stadium diversion percentages are larger than campus percentages because it’s a closed system, Williams said. Bag checks keep outside waste from coming into the stadium, so everything thrown away at football games came from the stadium.

OSU and UF have both worked on changing contracts with concession vendors to make sure that food containers and cups are compostable or recyclable.

When the University of Colorado-Boulder, which has a gold rating, created its campus master plan, its goal was to divert 85 percent of its waste by 2017.

Jack DeBell, CU-Boulder’s recycling program development director since 1985, said that document is now irrelevant. CU-Boulder has since changed its zero waste goal to 2020, but today the 30,265-student campus diverts 42.7 percent of its waste from the landfill, amounting to 2,358 tons of a total of 5,523 tons of waste produced.

“When you’ve already picked the low-hanging fruit off our campus, which we have, it gets harder and harder to continue to increase diversion by going after smaller and smaller material streams,” DeBell said. These smaller streams, he said, include toner cartridges, shrink wrap and lab glass.

DeBell said the most important move the university made was prioritize zero waste as a method for doing business.

“When administrations, faculty, custodians and students think about aspects that go into consumerism,” he said, “that’s zero waste for us.”

WHERE IT GOES

A bulldozer pushes waste into a trailer at Leveda Brown Environmental Park in Gainesville. Waste from Levy, Gilchrist and Alachua counties collects at Leveda Brown before being sent off an hour away to New River Landfill in Raiford.

Alachua County doesn’t have an operating landfill of its own. The county once had five landfills, but all of them have been closed since the early 1900s, which means they’re filled to capacity. Citizen groups said they didn’t want another, said Sally Palmi, assistant public works/waste management director in Alachua County.

Johnston noted that the U.S. falls behind when it comes to zero waste.

“Technologies that are deployed in other parts of the world are not as mainstream in this country,” she said. “We still think of landfilling as a viable option. It allows us to have that mentality of ‘I can throw that away,’ out of sight, out of mind.”

Tucked in a wooded area off Northeast State Road 24 is Leveda Brown Environmental Park, the transfer station where waste from Alachua, Gilchrist and Levy counties gathers before being sent to New River Regional Landfill.

Palmi said there’s still a mentality that it’s up to the county to sort through the garbage to find every recyclable, reusable part. But on the main floor of the transfer station, workers will pick out the noticeable items that can’t be thrown away, like refrigerators. Otherwise, items will be sloughed into a trailer below the floor, weighed and driven to New River.

Charlie Hobson, division manager of SP Recycling Corporation that operates out of the environmental park, said it’s common for unsorted recyclable items, such as the cardboard and plastic that comes with packages of bottled water, to go to the landfill. He said that if the packaging arrives with the cardboard inside the plastic, it’ll just be put in the landfill rather than separated.

DeBell, the recycling program development director for CU-Boulder, said attitudes toward recycling have changed over the last 30 years.

“I’ve seen recycling build from a token environmental effort to a practical, financially viable and socially acceptable way of reducing resources.”

Sustainability education is one of the biggest challenges universities face when striving for zero waste, from understanding what products are recyclable to learning how to compost.

“Zero waste is more of a journey than a destination,” DeBell said.

[A version of this story ran on page 1 - 3 on 4/14/2015]

1: PET or PETE (polyethylene terephthalate): soft drink, water and beer bottles, mouthwash, peanut butter, salad dressing.

2: HDPE (high density polyethylene): milk jugs, juice bottles, bleach, detergent, shampoo, butter and yogurt tubs

3: Vinyl or PVC: window cleaner, detergent, shampoo and cooking oil bottles

4: LDPE (low density polyethylene): squeezable bottles, dry cleaning and shopping bags

5: PP (polypropylene): some yogurt containers, syrup bottles, ketchup bottles, caps, and medicine bottles

6: PS (polystyrene): meat trays, egg cartons, aspirin bottles, some food containers

7: Miscellaneous: 3- and 5-gallon water bottles, DVD cases

Not recyclable: solo cups, plastic food packaging from Starbucks, anything brittle, plastic grocery bags (return to grocery store)