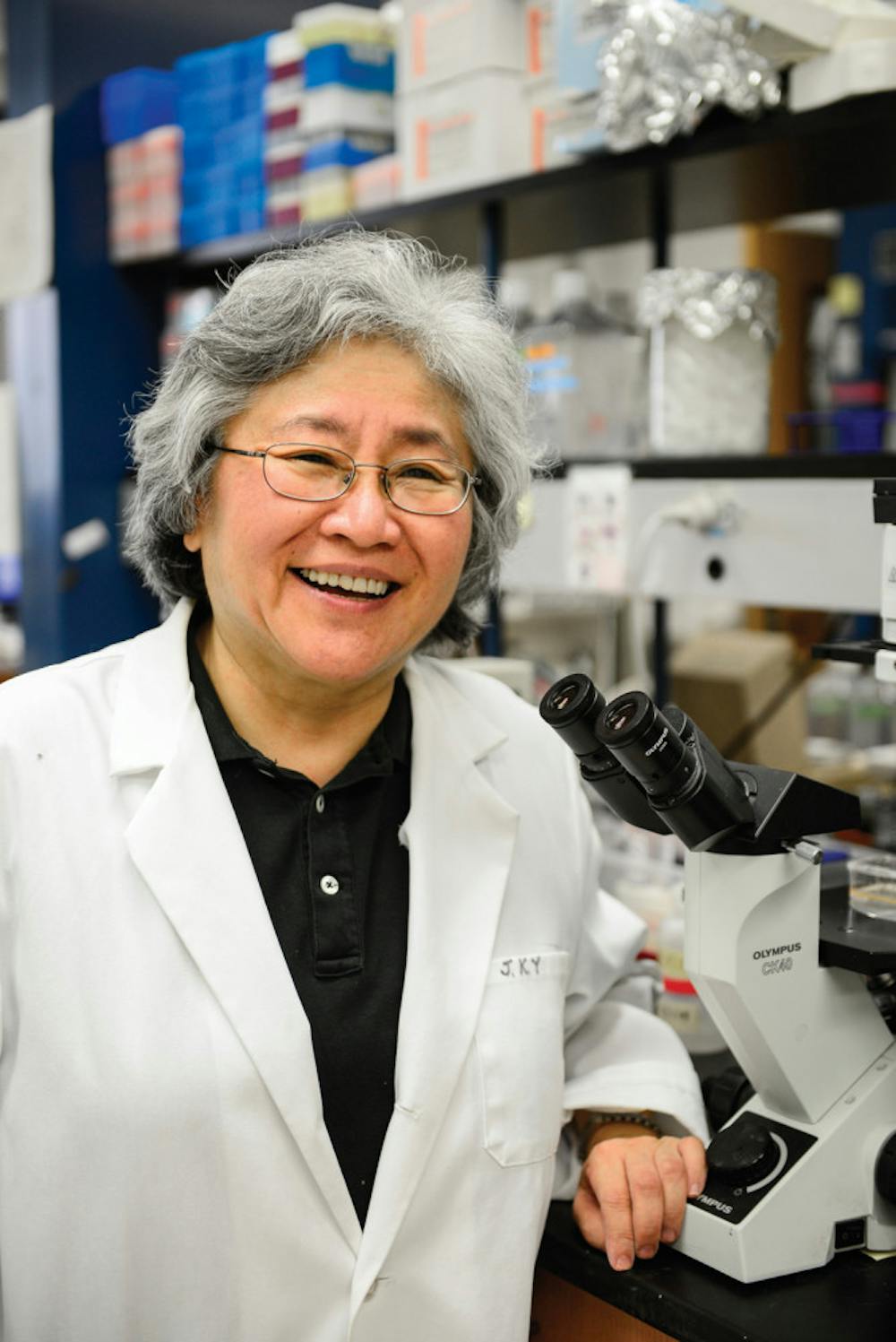

Janet Yamamoto, a UF professor in infectious diseases, discovered feline AIDS in 1986.

By comparing the feline and human viruses, FIV and HIV, she was able to find similarities in the sequences, she wrote in an email.

Yamamoto said the feline vaccine, released in 2002, works specifically with antiviral T cells that can kill the virus-infected cells without harming the normal cells. She said the study uses T cells from HIV-positive humans to see if they react with regions of the FIV protein to induce anti-HIV T cell activity.

The research found that the FIV protein stimulated human T cells to produce anti-HIV activity, which is why it could be used as a component to an HIV vaccine.

The vaccine won’t just benefit humans.

“The by-product of this HIV vaccine work will be the production of improved second-generation FIV vaccine,” she said. “Thus, our work will benefit both humans and cats.”

Students in the health science field agree this discovery could be a step in furthering HIV AIDS research.

“For HIV AIDS, they have a treatment, but you can’t cure it,” said Bao Pham, a 20-year-old first-year pharmacy student. “If they find a new way to treat it better, it’s really great.”

Yamamoto said the next step of her research is to test on at least two animal species before moving on to humans, as per Food and Drug Administration rules.

“The work described by Dr. Yamamoto has great promise as an approach to develop a vaccine against HIV AIDS,” said John Dame, chairman of the department of infectious diseases and pathology, in a statement. “It is a very exciting, fresh new approach to solving this major world health problem.”

A version of this story ran on page 3 on 10/8/2013 under the headline "‘Feline AIDS’ research promising for vaccines"

Janet Yamamoto, a UF professor in infectious diseases, has discovered a connection between feline AIDS and HIV that may lead to a vaccine for humans and a better vaccine for cats.