When I tell people I don't watch the Super Bowl, you'd think I told them I don't attend Easter Mass.

"Oh, because you like basketball?" they ask, affirming their question before I answer.

"No, I just don't really watch sports."

You'd think I told them I don't practice religion.

"Then what do you do?" is a typical response, as if watching a game is the only acceptable way to spend time.

Dare I answer, "Read?" "Run?"

I usually reply with the last.

"Oh, well running's a sport," they tell me, trying to comprehend the fact that they've just met a man, libido and all, who doesn't watch sports.

Actually running is not a sport, but that's beside the point.

And I do like sports, I just like a lot of other things more.

When I was 8, I'd decided I was going to be a football player. By the time I'd turned 16, I started considering other alternatives.

Photo courtesy of everyjoe.com

Photo courtesy of everyjoe.com

I understand sports. I know the rules and strategies to most games (cricket being the exception — what the f*** are they doing out there?), and though I could hardly name a single player in Sunday's game, I have a deep appreciation for what it takes to be a talented athlete, player and coach.

I also have a clear understanding of why we — men in particular — are often hypnotized by the movement of a ball and the collision of bodies.

Tracking is in our nature. As is an inclination towards violence (not violence per se, but an inclination towards it). Our ancestors survived in part due to their hand-eye coordination. The ability to accurately throw a spear, sling a rock and shoot an arrow gave them a hunting advantage. Men with poor coordination had similarly poor sex lives, while men who excelled at these tasks slept with as many women as they could feed.

Our ancestors came to venerate the most skilled hunters and strongest warriors, as they secured food and safety.

We've inherited this admiration. But we no longer need their benefits for survival, so we've adapted these talents to finely constructed games in which we can cater to our primitive drives.

Mounting evidence supports a theory that when we watch sports, our brains process the information as if we are actually participating. That is, we get the mental satisfaction of outmaneuvering Lionel Messi and tackling Reggie Bush, without actually having to do so.

This is why we watch sports, why we can be so mesmerized and passionate about the play on the field from the couch in our home. I respect the effort put forth by the players (despite my disgust with their salaries) and the enthusiasm of the fans.

But a note to the fans:

Whenever I watch sports, it seems that the vast majority of fans are distant from the game. They don't recognize the nuances of a perfectly placed through pass or the precision of an ace — they merely react, cheering when others cheer.

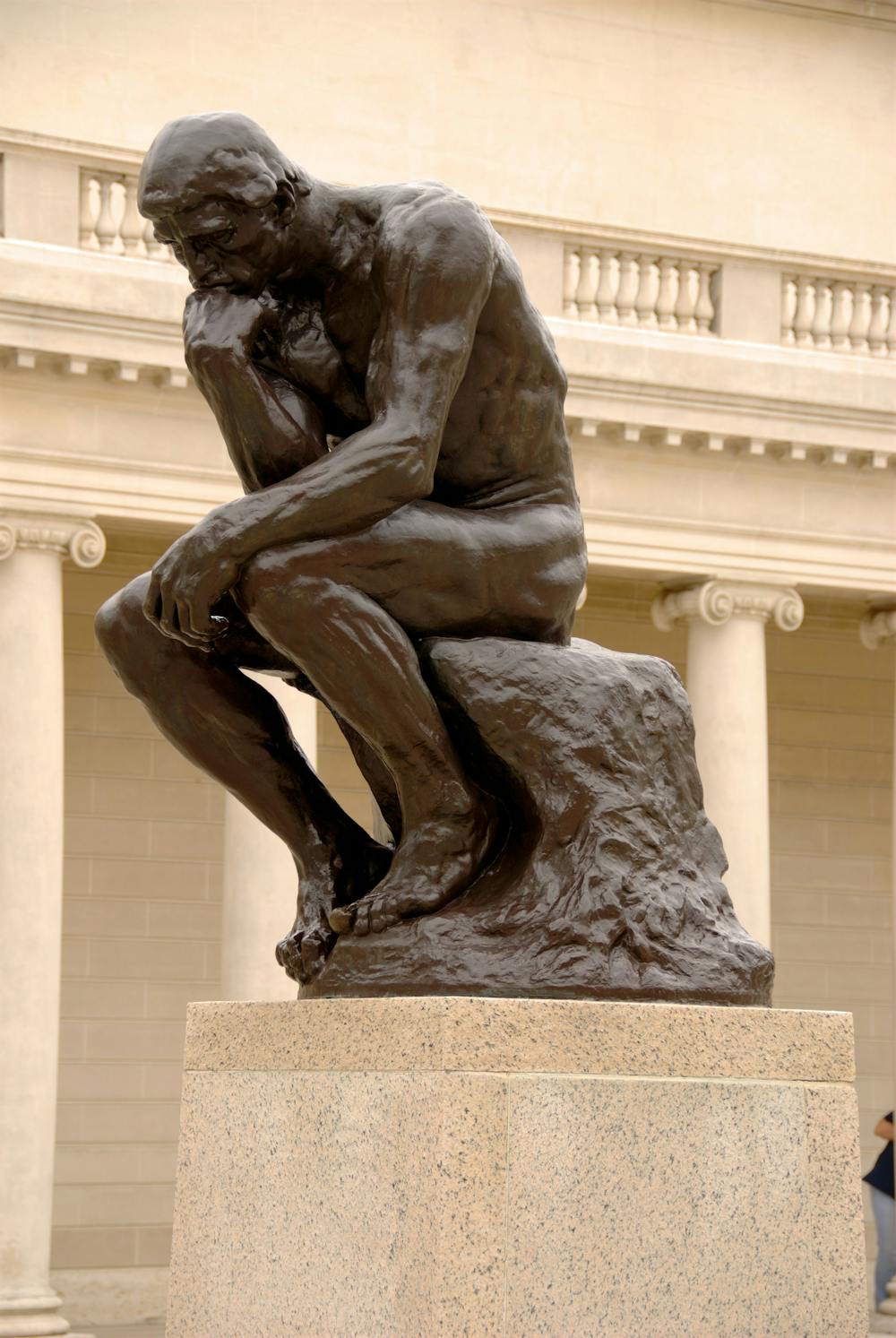

This is where philosophy can aid the fan.

By combining — and slightly reinterpreting — John Mill's concept of higher pleasures and Aristotelian arete (excellence), the sports fan can reclaim his appreciation for the game he devotes so much time to.

Rather than simply consuming the game, see the sport as an art form or a science, as something worthy of study and acute attention. Watch the entire field (or pitch or court) and notice the subtle responsibilities of each position. And when learning the strategies and formations, don't just learn them absent from game play; watch each individual play, recognize the formation used and consider what could have been done better.

In this way, sports can transcend its place as a "past time" where we go to waste our time and forget about all the things that actually "matter." Sports can — and should — claim a spot as a worthy study, not only for its primitive insight, but also for its artistic creation and scientific attention.

Above all, this meticulous analysis of a sport creates a more fulfilling experience for the fan. And, beyond the game, practicing this combination of higher pleasures and arete begets a more satisfying life for human beings.

Posts in Poor Philosophy appear on Tuesdays.

By combining and slightly reinterpreting John Mill's concept of higher pleasures and Aristotelian arete (excellence), the sports fan can reclaim his appreciation for the game he devotes so much time to.