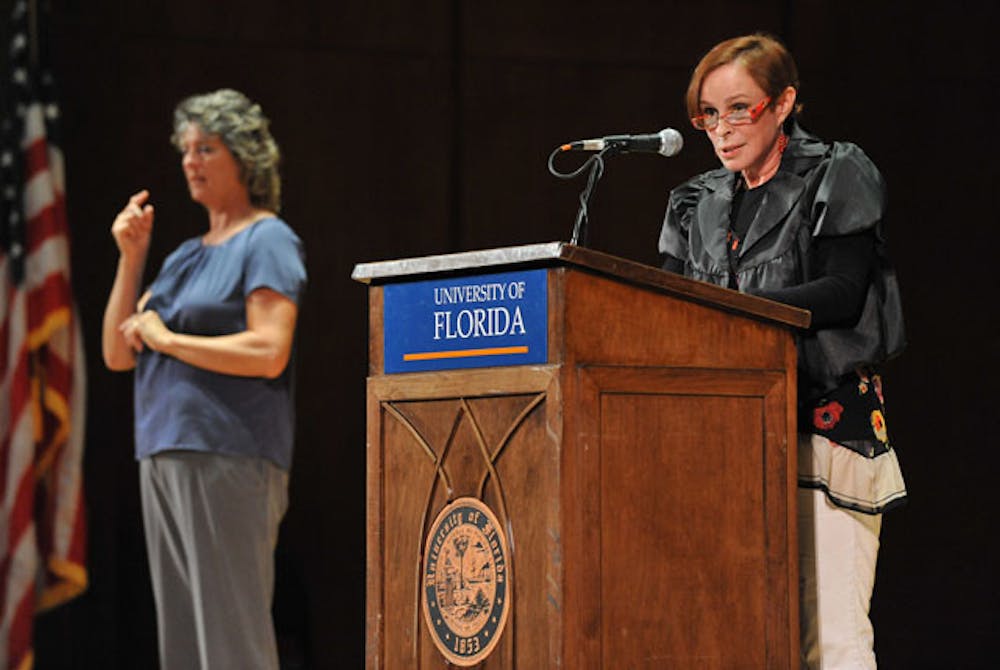

Alina Fernandez, daughter of Fidel Castro and outspoken critic of his regime, spoke to students Wednesday night to unravel the personal story of her father’s counterrevolution.

Fernandez, who wrote “Castro’s Daughter: An Exile’s Memoir of Cuba,” took a packed University Auditorium through her childhood and into her adult life. She escaped from Cuba through Spain in 1993. Still, the revolution follows her.

“What’s most bizarre,” she said, “is that I come from a country in which the revolution is endless.”

Fernandez described the defining point of her father’s counterrevolution as the moment in 1959 when her cartoons left the TV screen, replaced by an image of Castro descending the Cuban mountains alongside his fellow counterrevolutionaries.

“That’s when Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse vanished from my screen forever,” she said.

Fernandez laced her speech with humorous observations encountered along her journey.

She said that growing up as the child of Castro, with a mother who “made an army of her ideology” in support of communism, made it difficult to be around much of the Cuban population.

“You know you must be in real desperation to approach a child, expecting her to be helpful,” she said. “What is worse is that you can’t do anything to help.”

Though she says almost nothing has changed in Cuba since Castro assumed a term that lasted through 11 American presidencies, Fernandez compared the constant organization of Castro’s regime to a farm.

“In Cuba, health and attention and education are free, but you’re not paid for your work,” she said. “They make about a $10 salary a month at most. It’s a farm that belongs to the Castro family, in which you’re going to consume everything but they’re going to keep the money.”

Though she said the prospect of a rebellion is nearly impossible, Fernandez is hopeful that Cuba awaits a bright future. However, this will depend on the current generation.

“I think we’re waiting for each generation to pass away,” she said. “That generation is almost 80 years old now. They’ll have young people like [the audience members] willing to go back to the country.”

Her expectations of the Cuban youth, however, were not so optimistic. She said after the speech that their work ethic has declined as a result of communism.

“The basic quality is that they’re hopeless,” she said. “The best you can aspire to in Cuba is to become a barber or a hairdresser or a manicurist. That’s the maximum you can achieve now. That’s why people are able to get on a piece of wood and travel 90 miles through water full of sharks.”