Kofi Adu-Brempong was afraid he was going to be kidnapped, taken to Africa and slain in a ritual killing.

In the days leading up to his shooting and arrest on March 2, the 35-year-old Ghanan graduate student sent e-mails to the faculty and staff in the UF geography department, accusing them of scheming to kill him, said Keith Yearwood, Adu-Brempong’s friend and fellow graduate student.

The recent episode involving Adu-Brempong, who exhibited psychotic and delusional behavior, has brought increased attention to the issues of mental health and campus safety. The UF Dean of Students Office has several programs in place to help students suffering from mental health problems, said Wayne Griffin, the associate director of the UF Counseling Center.

One such program, the Critical Response Team, or CRT, is composed of safety and mental health professionals including professors, police officers, counselors and housing coordinators, he said.

The day before Adu-Brempong was arrested and shot, a CRT counselor, along with a University Police Department officer and Adu-Brempong’s adviser, visited him at his apartment in Corry Village for two and a half hours, according to a police report.

The counselor, Laura Templeton, did not get a good chance to talk with Adu-Brempong and was unable to determine his overall mental state, Griffin said. No counselors came the night of the shooting because the situation had become too volatile and dangerous.

When Templeton met with Adu-Brempong the day before the incident, she determined Adu-Brempong did not meet the criteria for the Baker Act, according to the report.

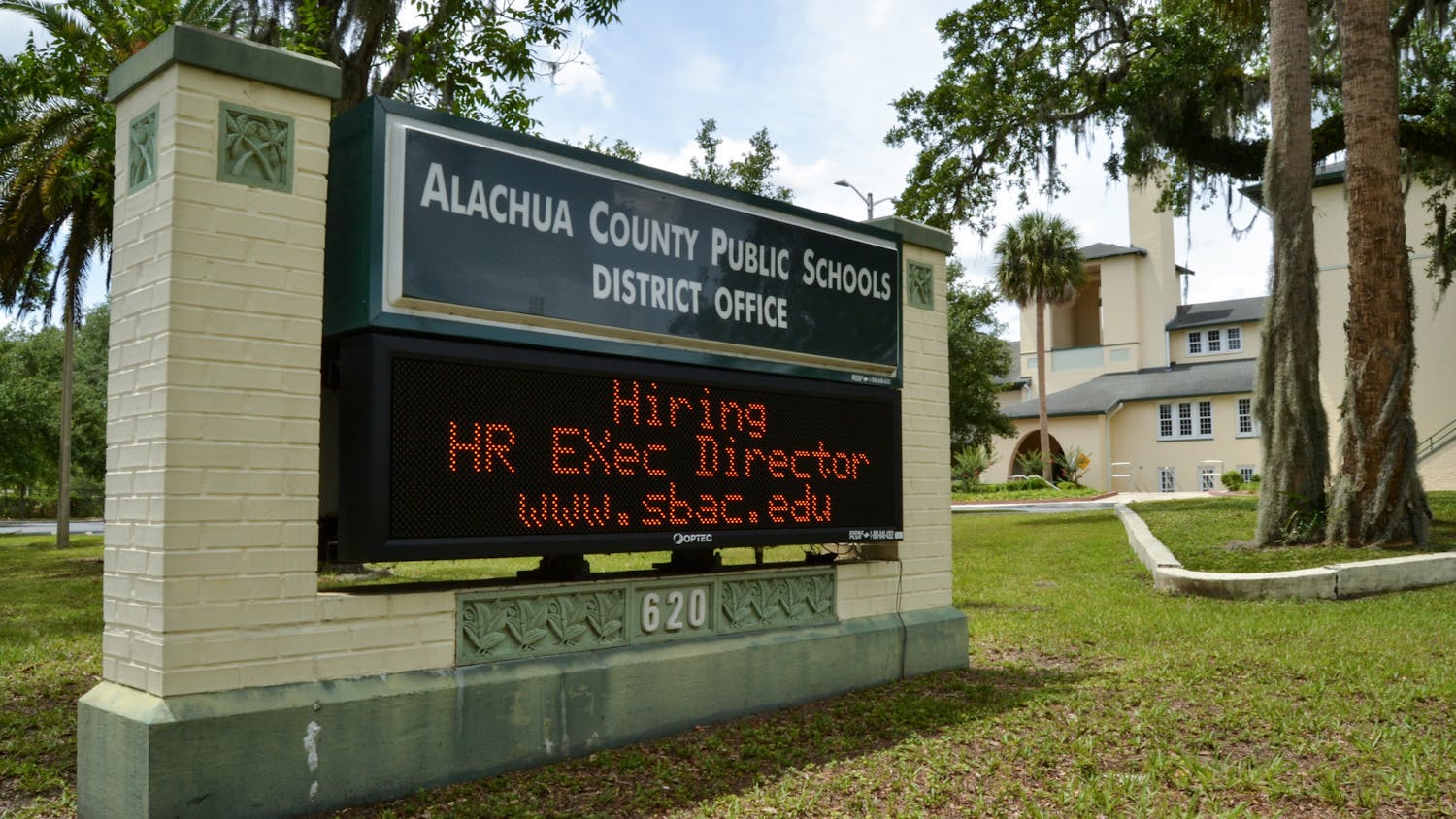

Had he been submitted under the Baker Act, Adu-Brempong would have been taken to one of two crisis units in Alachua County where he would have remained under observation for up to three days, said Bruce Stevens, a professor in the UF College of Medicine.

Stevens is also a member of the UF Faculty Senate and the co-president of the Gainesville chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

As a member of NAMI, he is an instructor for the Alachua County Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, an organization that trains police officers and 911-dispatch operators to handle emergencies involving citizens suffering from mental-health problems. The CIT training, which was first offered in Alachua County about six years ago, is a 40-hour series of lectures, videos, field trips and role-playing scenarios designed to help officers understand mental-health issues, Stevens said.

About 400 UPD officers, the Gainesville Police Department and the county sheriff’s office have gone to the training facility and graduated from the program, he said.

Between two and four of the five UPD officers who were in Adu-Brempong’s apartment when he was shot had been through CIT training, he said. Keith Smith, who shot Adu-Brempong, had not undergone training, he said.

Stevens is calling for an additional investigation to determine if the officers involved in the incident violated what they learned in the CIT course.

“The implementation of what the officers learned in CIT training broke down,” he said. “I don’t know what happened.”

Before the standoff and arrest, other breakdowns prevented Adu-Brempong from getting the mental care he needed, he said.

“There were several times on [the day before and the day of the shooting] that the Baker Act should have been employed,” he said.

The Baker Act involves withdrawing someone's constitutional rights. Universities and cities merge crime prevention and mental health care differently, he said.

In 1988, the first-ever crisis intervention team was created by the Memphis Police Department after officers shot and killed a man suffering from hallucinations, Stevens said.

Since then, universities and cities across America have adopted their own systems for merging mental health care with police affairs. After the shooting at Virginia Tech when Seung-Hui Cho killed 32 people before taking his own life, the university tried to strengthen its ability to respond to students in distress.

One measure was the creation of the Threat Assessment Team, a collaboration between several university departments and UPD.

According to the university’s Web site, the team determines if individuals pose threats to themselves or others and intervenes when necessary to maintain campus safety.

The creation of the multidisciplinary team led to more dialogue between the counseling department and UPD. Christopher Flynn, psychologist and counselor for the Cook Counseling Center, said he meets with the Threat Assessment Team regularly.

“We talk ... two to three times a week, about any students that may be of concern,” he said.

But Eugene Zdziarski, the vice president of student affairs at Roanoke College in Virginia, said students also play an important role in helping students with mental problems.

Zdziarski, former dean of students at UF, has written several books and papers on campus safety. He said many people feel reporting on troubled students will get them in trouble.

“Everybody on campus needs to take on responsibility to intervene,” he said. “They’re not getting them into trouble. They’re getting them out of trouble.”

Yearwood, who is now teaching Adu-Brempong’s class, did not think the e-mails he received from Adu-Brempong, who suffered from polio, were a big deal.

UF has historically done a good job of helping students suffering from mental health problems, but the UF administration should do everything it can to makes sure the issues can be discussed openly, he said.

“You’re never going to stop every situation from happening,” he said.