It won't be long until purchasing fruit at the grocery store is far from a sticky situation.

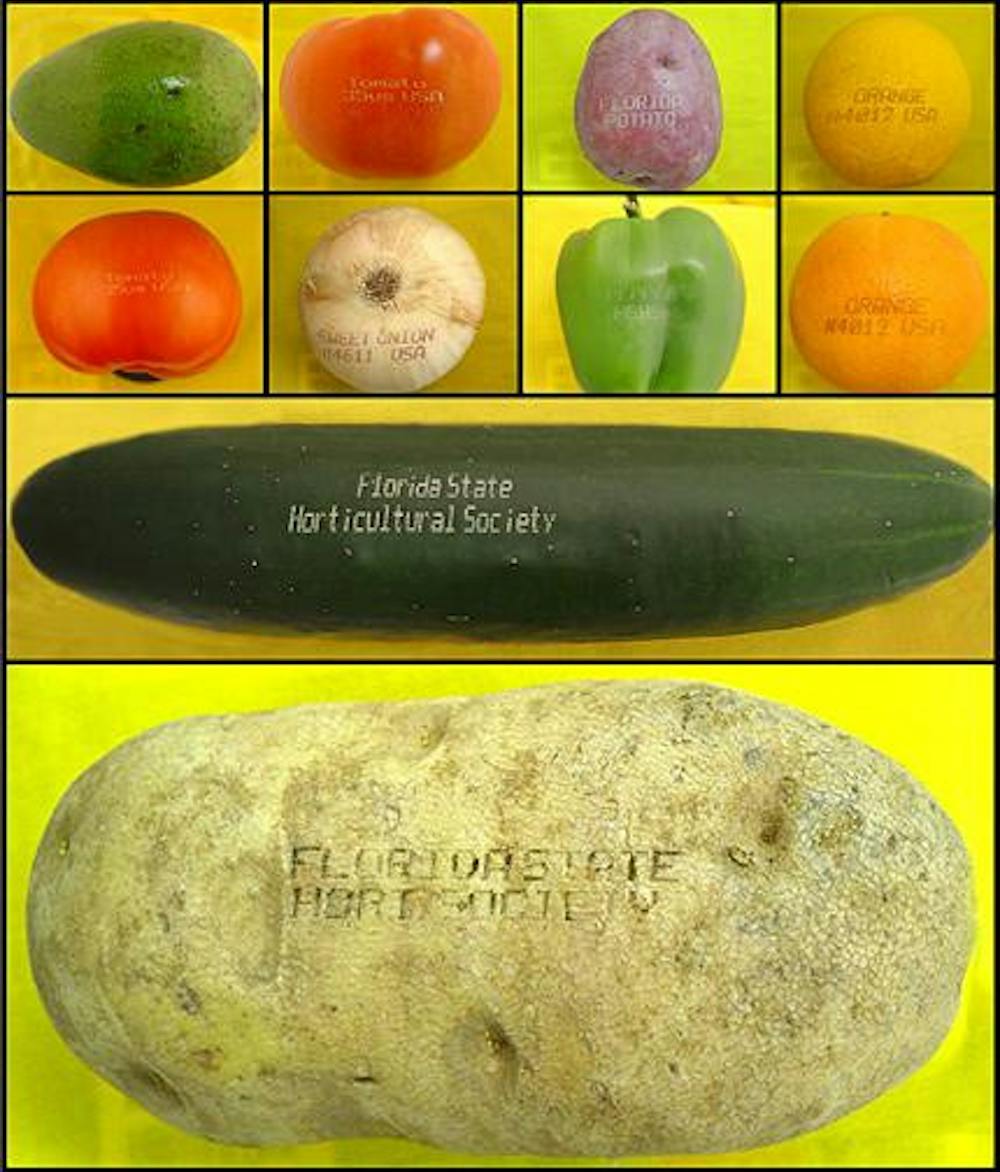

UF researchers are in the final stages of testing a new system, called laser etching, which uses light energy to place traceback information directly on fruit as an alternative to the sticky adhesive labels usually used.

Traceback information includes where the fruit was packaged and sometimes where it was grown.

Greg Drouillard, a former senior engineering research scientist for the center, was in Ben Hill Griffin Hall at the center in 1994 when he overheard discussion about an alternative to the problem of expensive adhesive labels.

"It gave me something to think about," he said. "So I started to come up with ideas on my own."

One of those ideas became the laser-etching system. With laser etching, the wavelength of a laser is set specifically to remove a fruit or vegetable's pigment, located a few cell layers deep on the surface of the produce, as it passes by.

Ed Etxeberria, a professor in the department of horticultural sciences at UF, is on the testing team at the Citrus Research and Education Center in Lake Alfred, Fla. He said they are testing the new system on a variety of fruits to see how it affects appearance, rates of decay and water loss.

The results so far have led Etxeberria to determine that the light actually sterilizes the treated area, thus eliminating the growth of decay organisms, yet it allows for increased dehydration of the fruit.

"At the packinghouse, the label is placed after the fruit has been washed and waxed," he said. "If packers place a second layer of wax on just the labeled area, now it's sealed and we avoid all problems."

Etxeberria, along with U.S. Department of Agriculture microbiologist Jan Narciso and graduate student Preeti Sood, is now testing for the potential infiltration of human pathogens. Etxeberria said the tests are critical, as laser etching is the only non-removable way to label fruit.

"This system is the only one with permanent traceback," he said. "Before, the stickers could fall off or be switched."

The process also could provide new advertising methods, allowing companies to create their unique logos to be placed directly on the fruit, said Steven Sargent, a professor of post-harvest pathology at UF.

Drouillard, now the director of laser research and technology for Sunkist Growers and owner of Laser Applications Technologies, first released his system in 2005.

Drouillard said the testing should be completed by the end of October. Once the FDA approves laser etching, he said it wouldn't take long before the system is widely used.