On a hot, muggy, summer day in Georgia, two black couples were seized by a mob of white men. They were taken to a clearing overlooking a nearby river — the Apalachee, some 15 miles from where the University of Georgia stands today. There, they were tied up and shot to death — the coroner’s report estimated they were shot as many as 60 times. One of the women was pregnant; though it isn’t certain, some reports claim the unborn child was ripped out from her body.

No one was ever prosecuted.

It’s a story with elements all too familiar to those which have looked at American history in the Jim Crow period. But that’s where these stories seem to stay: nestled comfortably in the pages of history textbooks and old newspaper clippings, just within reach yet comfortably out of sight.

That’s the way we’ve dealt with our history of lynching for a while, anyway. But reality isn’t so easy to hide from. That particular mass lynching occurred in 1946, which wasn’t all that long ago. Plenty of people are alive today who were alive when those couples were lynched. The FBI has reopened its investigation of the lynching, and it is currently questioning several men in their 80s and 90s and gathering evidence about their involvement.

We aren’t as far removed from lynchings as we’d like to think.

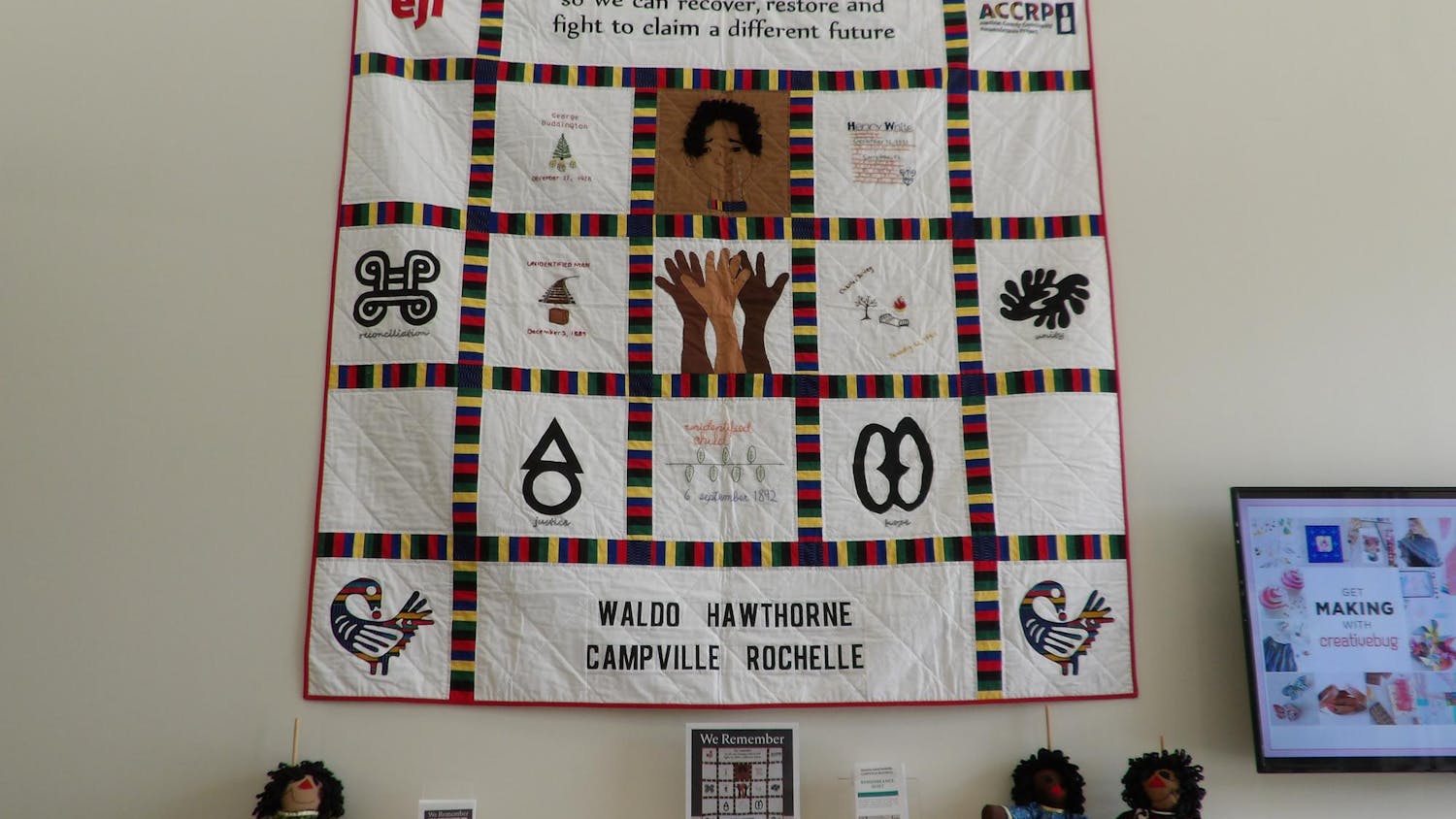

A report published last week by the Equal Justice Initiative showed nearly 4,000 black people were lynched in the South from 1877 to 1950, which is 700 more names than earlier estimates. The report calls these murders “racial terror lynchings.” Much like Islamic State group’s execution videos, these lynchings were public events — dramatic and tragic. They weren’t simply isolated murders carried out by a handful of angry young men — they were announced in newspapers and commemorated with postcards. The theatrical ferocity of these murders, that they occurred independently of crime and execution rates, that they were used to reinforce the racial status quo — all suggest lynchings were used to terrorize the black community.

It’s a legacy that’s been largely ignored but shouldn’t be any longer. The Equal Justice Initiative is campaigning to put memorials and markers in the thousands of sites where people were lynched. It’s a legacy relevant to us, no matter what our identity; Alachua county had the second-highest number of lynchings in Florida. We live an hour away from Rosewood, a once-populated black town that was raided and burned to ashes by white mobs in 1923.

It’s something that still haunts everything around us, from the woods and one-light towns right up to the biggest cities. We hope EJI succeeds in its efforts to memorialize lynchings. It’s absolutely essential that we wrestle with the darkest parts of our history and confront this legacy.

[A version of this story ran on page 6 on 2/17/2015 under the headline “Past lynchings are still part of our present"]