Michael Tuccelli listened to the sound of a chirping frog for over an hour, fascinated.

Tuccelli, a professor at UF, never heard a sound until six years ago. Born deaf, he learned sign language to communicate until getting a cochlear hearing implant.

The implant is an electronic device that gives a deaf person the sense of hearing by stimulating the hearing nerve in the brain.

Before getting the implant, Tuccelli adapted by learning other methods of communicating with people.

“My mother would point to a picture, and then to the word,” Tuccelli said. “She also tried teaching me lip-reading, but that wasn’t very effective.”

With his own children, Tuccelli took a different approach. He has three hearing children who could all sign to a certain extent before they could actually speak, something Tuccelli sees as an advantage.

Tuccelli said exposing his children to sign language improved communication with their parents because associating signs with concepts and words was easier and faster than learning the sound. Plus, early exposure to signing enhanced their imagination.

Now, Tuccelli teaches three levels of American Sign Language at UF. Learning ASL is proven to increase job security and IQ levels, Tuccelli said.

“It’s great to know how to communicate with another culture,” said Angela Petrizzo, a UF student enrolled in Tuccelli’s class. “Dr. Tuccelli teaches us about a whole new culture.”

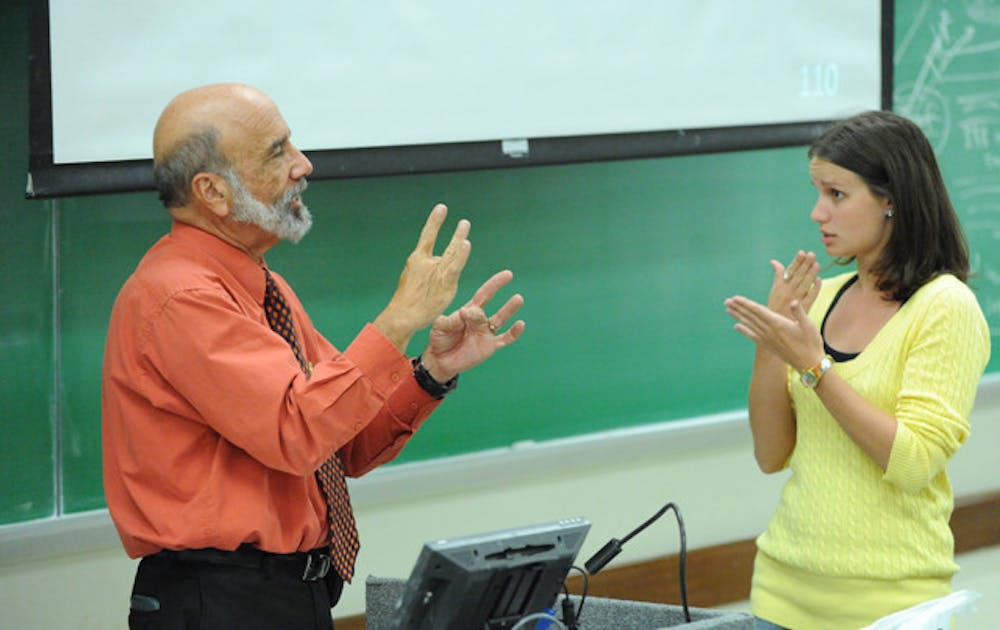

Tuccelli takes an interactive approach to teaching his ASL students, taking what they already know and relating that to a visual language.

“They are amazed at how they can express themselves,” Tuccelli said.

Ninety-three percent of communication is nonverbal, making it important to be aware of body language, he said. American Sign Language takes this concept and enforces it, making everything from hand gestures to facial expressions important in conversations.

“I love being able to communicate in a whole different way,” said Alison Schultheis, another student in Tuccelli’s class.

With the people who he interacts with, he receives different reactions to being deaf.

First impressions are usually apologetic. After that, people will either walk away or try to communicate with him by talking slowly and fish-like, Tuccelli said.

Tuccelli sometimes conducts an experiment with his ASL students to help them understand what it is like being deaf in a hearing world.

In the experiment, he sends students to Oaks Mall in pairs, one pair signing to each other, and the other speaking verbally. After visiting different stores, the students see that the signing pair is approached less, showing the lack of interaction with “deaf” people.

For Tuccelli, shifting from this separation because he was deaf to being a part of the hearing world came with challenges.

Tuccelli compared his learning to hear to someone learning to see for the first time. Just as they would have to understand hues, textures and perception, he had to interpret different pitches, volumes and tones.

All these challenges have not held Tuccelli back from doing what he loves. He enjoys sharing his culture with his students and participating in different activities, just like anyone else.

Every year, Tuccelli organizes a motorcycle trip to Alaska to raise money for deaf children and their families.

“My father told me, ‘If you can’t do it, do it,’” Tuccelli said.